2.7.1: Monocots and Eudicots

- Page ID

- 47651

Learning Objectives

- Compare and contrast monocots and eudicots.

- Differentiate between monocot and eudicot flowers and leaves.

Of over 400 families of angiosperms, some 80 of them fall into a single clade, called monocots because their seeds have only a single cotyledon. The remainder have seeds that produce two cotyledons (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). This group includes some early diverging angiosperms (ANA grade families and magnoliids), but the large majority of these occupy a single clade called the eudicots. In addition to developmental features, there are a few morphological and anatomical traits you can use to distinguish between these two major groups.

Monocots

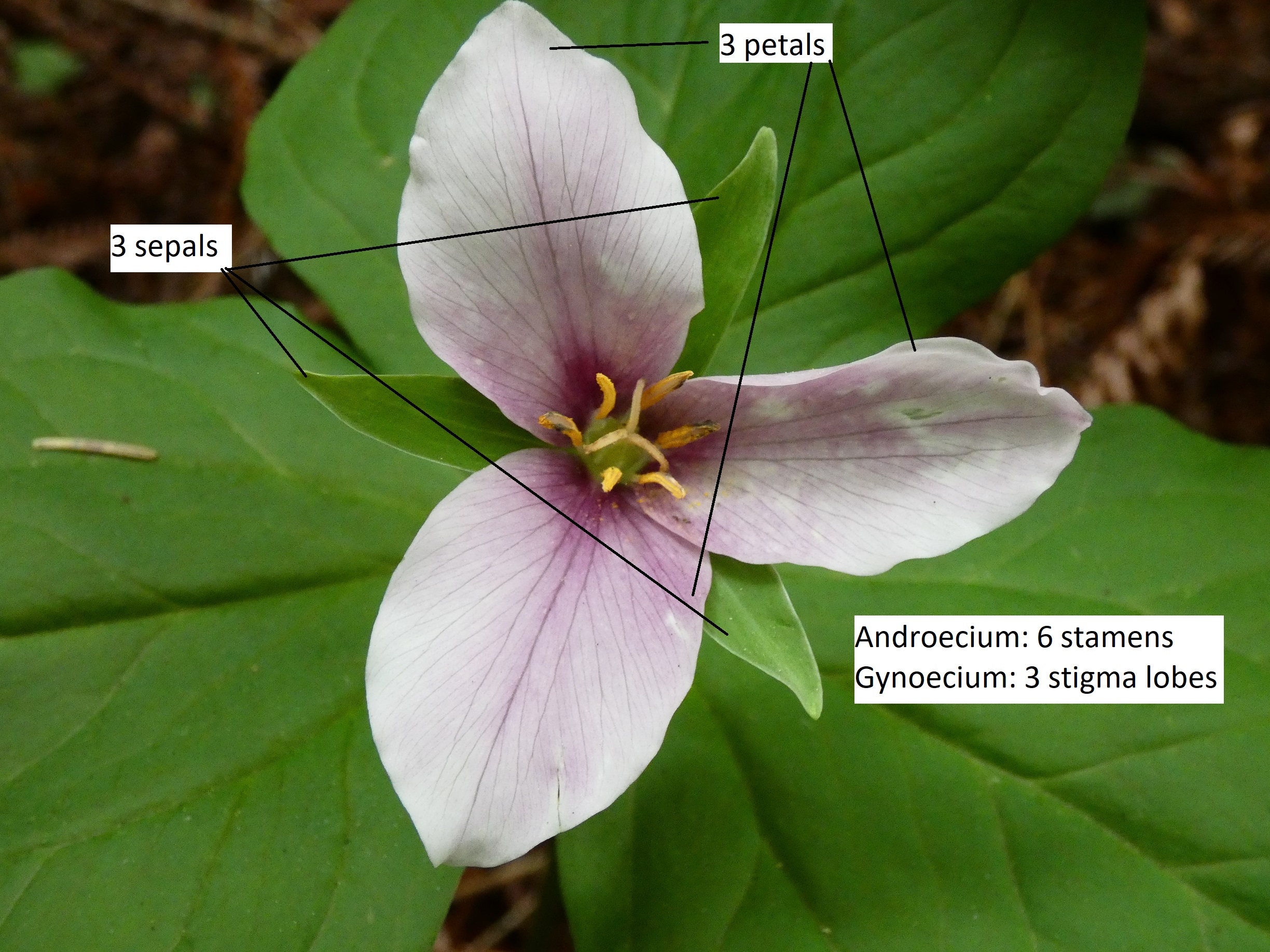

Monocots have a single cotyledon in their seed, parallel venation in their leaves (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)), flower parts in multiples of three (3-merous, see Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)), and vascular bundles dispersed throughout the stem in concentric circles. Monocots do not have true secondary growth, though some (such as bamboo) form tough, woody stems.

Some major groups of monocots are:

- palms (Arecaceae)

- orchids (Orchidaceae)

- yams, sweet potatoes (Dioscoreaceae)

- lilies, onion, asparagus (Liliaceae)

- bananas (Musaceae)

- all the grasses (Poaceae), which include many of our most important plants such as

- corn (maize)

- wheat

- rice

- and all the other cereal grains upon which we depend so heavily for food as well as

- sugar cane and bamboo

Eudicots

Eudicots have two cotyledons in their seeds, netted venation in their leaves (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)), flower parts in multiples of 4 or 5 (4-merous or 5-merous, see Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)), and vascular bundles in the stem arranged in a radial pattern like spokes of a wheel.

Attribution

Content by Maria Morrow, CC-BY