2.2.2: Viruses

- Page ID

- 31914

Learning Objectives

- Describe the general characteristics of viruses

- Describe the range of effects viral infections can have on plants

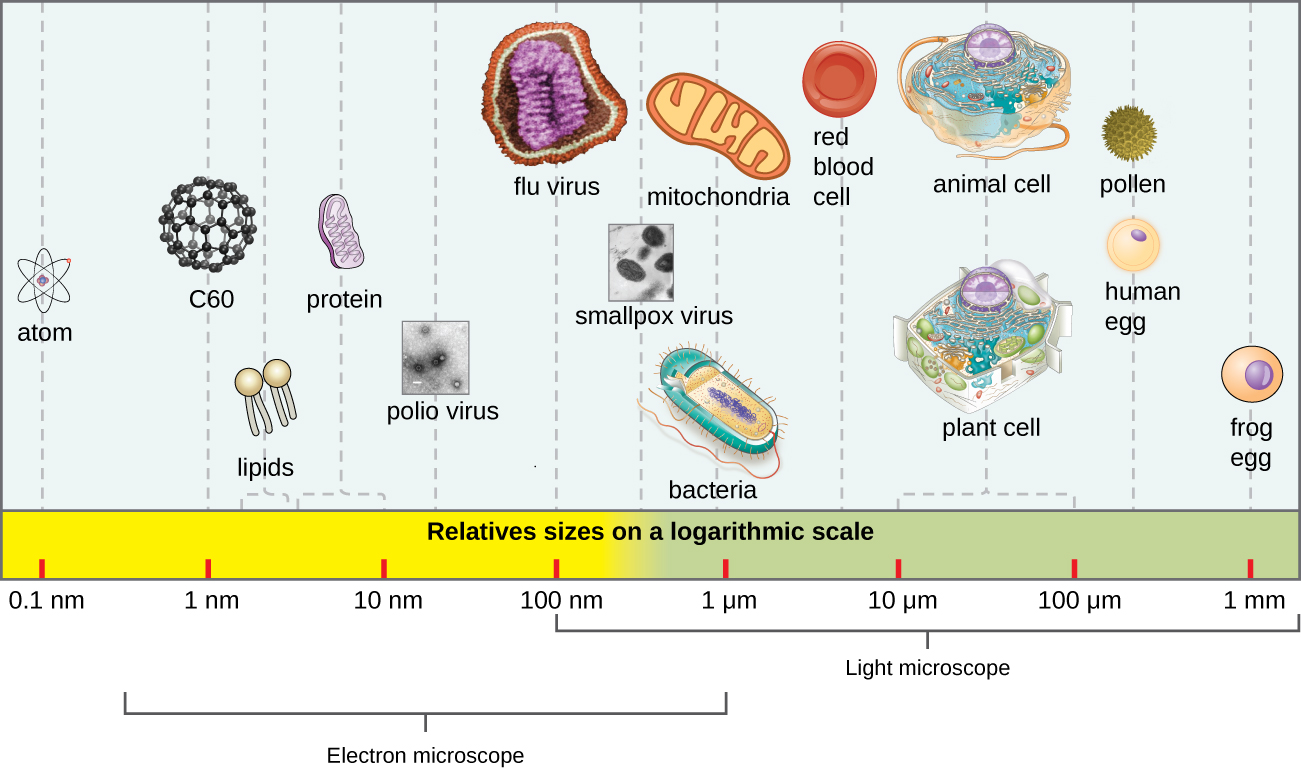

Viruses are microscopic (see Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) for scale), acellular, and contain nucleic acids. Despite their small size, which prevented them from being seen with light microscopes, the discovery of a filterable component smaller than a bacterium that causes tobacco mosaic disease (TMD) dates back to 1892.1 At that time, Dmitri Ivanovski, a Russian botanist, discovered the source of TMD by using a porcelain filtering device first invented by Charles Chamberland and Louis Pasteur in Paris in 1884. Porcelain Chamberland filters have a pore size of 0.1 µm, which is small enough to remove all bacteria ≥0.2 µm from any liquids passed through the device. An extract obtained from TMD-infected tobacco plants was made to determine the cause of the disease. Initially, the source of the disease was thought to be bacterial. It was surprising to everyone when Ivanovski, using a Chamberland filter, found that the cause of TMD was not removed after passing the extract through the porcelain filter. So if a bacterium was not the cause of TMD, what could be causing the disease? Ivanovski concluded the cause of TMD must be an extremely small bacterium or bacterial spore. Other scientists, including Martinus Beijerinck, continued investigating the cause of TMD. It was Beijerinck, in 1899, who eventually concluded the causative agent was not a bacterium but, instead, possibly a chemical, like a biological poison we would describe today as a toxin. As a result, the word virus, Latin for poison, was used to describe the cause of TMD a few years after Ivanovski’s initial discovery. Even though he was not able to see the virus that caused TMD, and did not realize the cause was not a bacterium, Ivanovski is credited as the original discoverer of viruses and a founder of the field of virology.

Today, we can see viruses using electron microscopes (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)) and we know much more about them. Viruses are distinct biological entities; however, their evolutionary origin is still a matter of speculation. In terms of taxonomy, they are not included in the tree of life because they are acellular (not consisting of cells). In order to survive and reproduce, viruses must infect a cellular host, making them obligate intracellular parasites. The genome of a virus enters a host cell and directs the production of the viral components, proteins and nucleic acids, needed to form new virus particles called virions. New virions are made in the host cell by assembly of viral components. The new virions transport the viral genome to another host cell to carry out another round of infection. Table \(\PageIndex{1}\) summarizes the properties of viruses.

| Characteristics of Viruses |

|---|

| Infectious, acellular pathogens |

| Obligate intracellular parasites with host and cell-type specificity |

| DNA or RNA genome (never both) |

| Genome is surrounded by a protein capsid and, in some cases, a phospholipid membrane studded with viral glycoproteins |

| Lack genes for many products needed for successful reproduction, requiring exploitation of host-cell genomes to reproduce |

Viruses and Plants

Viruses can infect every type of host cell, including those of plants, animals, fungi, protists, bacteria, and archaea. Most viruses will only be able to infect the cells of one or a few species of organism. This is called the host range. However, having a wide host range is not common and viruses will typically only infect specific hosts and only specific cell types within those hosts. The viruses that infect bacteria are called bacteriophages, or simply phages. The word phage comes from the Greek word for devour. Other viruses are just identified by their host group, such as fungal or plant viruses. Once a cell is infected, the effects of the virus can vary depending on the type of virus. Viruses may cause abnormal growth of the cell or cell death, alter the cell’s genome, or cause little noticeable effect in the cell. Some viruses, like TMV, cause disease and inhibit plant growth (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)). In other cases, scientists are finding that viruses can confer adaptive traits to their hosts, such as heat tolerance in the grass geyser's Panicum (see Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)).

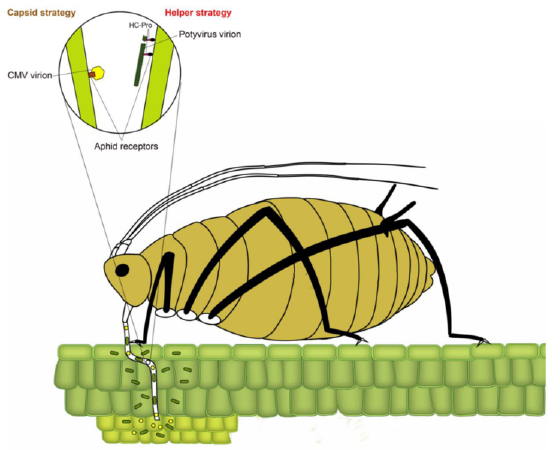

Viruses can be transmitted through direct contact, indirect contact with contaminated materials, or through a vector: an animal that transmits a pathogen from one host to another. Arthropods such as mosquitoes, ticks, and flies, are typical vectors for viral diseases, and they may act as mechanical vectors or biological vectors. Mechanical transmission occurs when the arthropod carries a viral pathogen on the outside of its body and transmits it to a new host by physical contact. Biological transmission occurs when the arthropod carries the viral pathogen inside its body and transmits it to the new host through biting. Most plant viruses are transmitted by aphids (see Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)).

Summary

Viruses are acellular, obligate intracellular parasites. They are composed of a nucleic acid (either DNA or RNA), a protein coat, and occasionally lipids. Viruses are not considered living because they are not composed of cells. However, viruses have important impacts on the life histories of organisms. As agents of disease, viruses contribute to top-down population control. They can also influence host biology in positive ways, such as thermal tolerance in panic grasses. Viruses can be spread from host to host by vectors. Sucking insects like aphids are important viral vectors for plants, as they transmit viruses into the vascular system.

Footnotes

1 H. Lecoq. “[Discovery of the First Virus, the Tobacco Mosaic Virus: 1892 or 1898?].” Comptes Rendus de l’Academie des Sciences – Serie III – Sciences de la Vie 324, no. 10 (2001): 929–933.

2 L.M. Marquez, R.S. Redman, R.J. Rodriguez, and M.J. Roossinck. (2007) A virus in a fungus in a plant: Three-way symbiosis required for thermal tolerance. Science. Vol 315. DOI: 10.1126/science.1137195

Attribution

Content authored and curated by Maria Morrow, CC-BY-NC, using the following source:

Nina Parker, (Shenandoah University), Mark Schneegurt (Wichita State University), Anh-Hue Thi Tu (Georgia Southwestern State University), Philip Lister (Central New Mexico Community College), and Brian M. Forster (Saint Joseph’s University) with many contributing authors. Original content via Openstax (CC BY 4.0; Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction)