7.1: Introduction

- Page ID

- 24878

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Introduction: The Cell Cycle and Mitosis

The cell cycle refers to a series of events that describe the metabolic processes of growth and replication of cells. The bulk of the cell cycle is spent in the “living phase”, known as interphase. Interphase is further broken down into 3 distinct phases: G1 (Gap 1), S (Synthesis) and G2 (Gap 2). G1 is the phase of growth when the cell is accumulating resources to live and grow. After attaining a certain size and having amassed enough raw materials, a checkpoint is reached where the cell uses biochemical markers to decide if the next phase should be entered. If the cell is in an environment with enough nutrients in the environment, enough space and having reached the appropriate size, the cell will enter the S phase. S phase is when metabolism is shifted towards the replication (or synthesis) of the genetic material. During S phase, the amount of DNA in the nucleus is doubled and copied exactly in preparation to divide. The chromosomes at the end of G1 consist of a single chromatid. At the end of S phase, each chromosome consists of two identical sister chromatids joined at the centromere. When the DNA synthesis is complete, the cell continues on to the second growth phase called G2. Another checkpoint takes place at the end of G2 to ensure the fidelity of the replicated DNA and to re-establish the success of the cell’s capacity to divide in the environment. If conditions are favorable, the cell continues on to mitosis.

Eukaryotic cell cycle is governed by the expression of cyclin proteins along with their activity. Credit: Jeremy Seto (CC-BY-SA)

Mammalian cells in culture going through the Cell Cycle. Green marker proteins expressed during the G1 phase. Red marker proteins are expressed during S/G2/M. During the G1 to S transition, fluorescence disappears as the marker proteins also transition in expression.

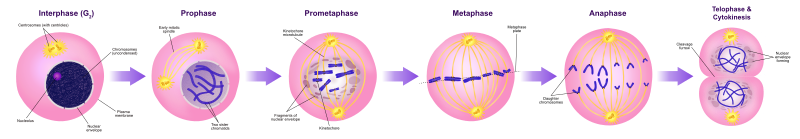

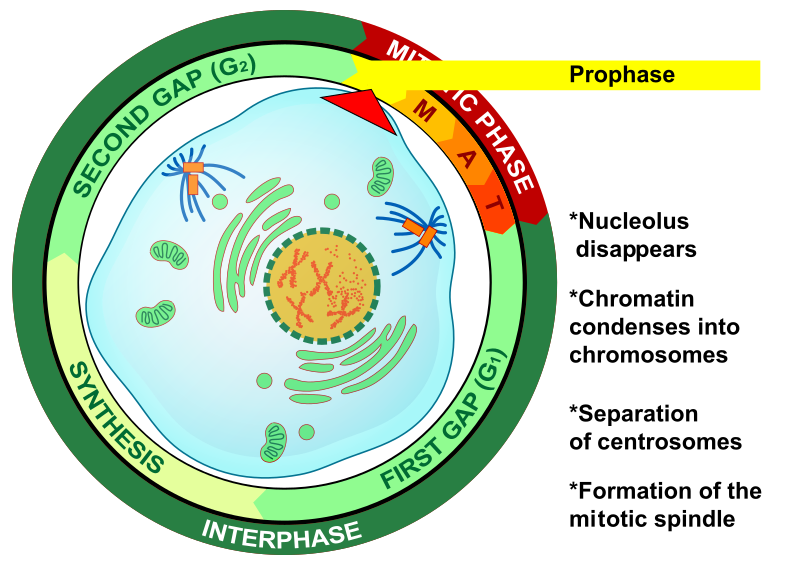

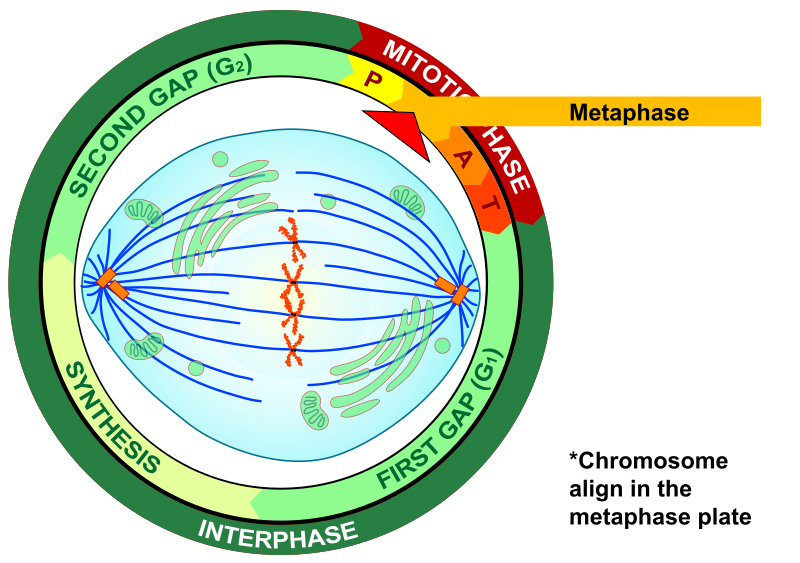

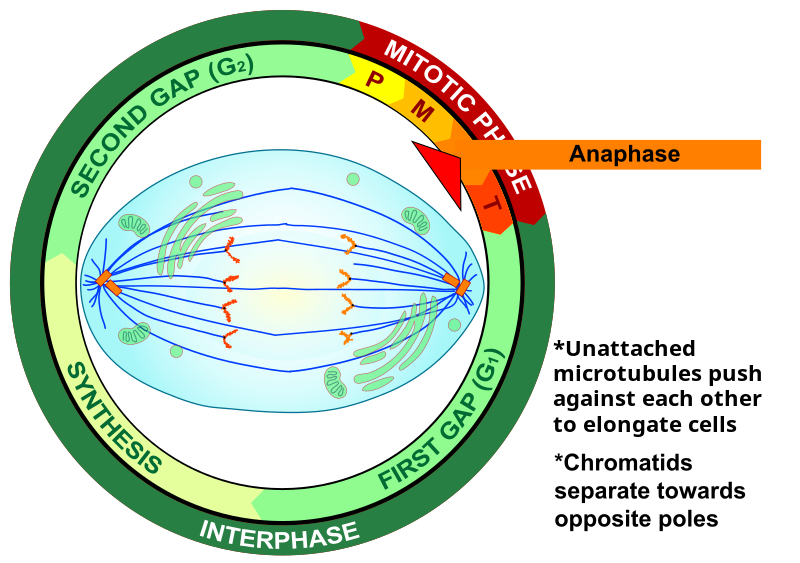

Mitosis is the process of nuclear division used in conjunction with cytokinesis to produce 2 identical daughter cells. Cytokinesis is the actual separation of these two cells enclosed in their own cellular membranes. Unicellular organisms utilize this process of division in order to reproduce asexually. Prokaryotic organisms lack a nucleus, therefore they undergo a different process called binary fission. Multicellular eukaryotes undergo mitosis for repairing tissue and for growth. The process of mitosis is only a short period of the lifespan of cells. Mitosis is traditionally divided into four stages: prophase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase. The actual events of mitosis are not discreet but occur in a continuous sequence—separation of mitosis into four stages is merely convenient for our discussion and organization. During these stages, important cellular structures are synthesized and perform the mechanics of mitosis. For example, in animal cells, two microtubule-organizing centers called centrioles replicate. The pairs of centrioles move apart and form an axis of proteinaceous microtubules between them called spindle fibers. These spindle fibers act as motors that pull at the centromeres of chromosomes and separate the sister chromatids into newly recognized chromosomes. The spindles also push against each other to stretch the cell in preparation of forming two new nuclei and separate cells. In animal cells, a contractile ring of actin fibers cinches together around the midline of the cell to coordinate cytokinesis. This cinching of the cell membrane creates a structure called the cleavage furrow. Eventually, the cinching of the membrane completely separates into two daughter cells. Plant cells require the production of new cell wall material between daughter cells. Instead of a cleavage furrow, the two cells are separated by a series of vesicles derived from the Golgi. These vesicles fuse together along the midline and simultaneously secrete cellulose into the space between the two cells. This series of vesicles is called the cell plate.

Mitosis Review

Binary Fission

Mitosis refers to nuclear division, which happens to coincide with cytokinesis. Prokaryotes do not have nuclei, therefore they do not undergo a process of mitosis. Instead, prokaryotes undergo the process of binary fission. Growth of new membranes during the cellular growth and expansion in a prokaryote occurs by 2 mechanisms 1) along the center of the cell or 2) apically.

The chromosome of prokaryotes is organized in a circular form. A mechanism called the rolling circle model describes the replication of the chromosome that accompanies binary fission. This is also the mechanism utilized by extrachromosomal DNA called plasmids.

Introduction: Meiosis

Meiosis is a process of nuclear division that reduces the number of chromosomes in the resulting cells by half. Thus, meiosis is sometimes called “reductional division.” For many organisms, the resulting cells become specialized “sex cells” or gametes. In organisms that reproduce sexually, chromosomes are typically diploid (2N) or occur as double sets (homologous pairs) in each nucleus. Each homolog of a pair has the same sites or loci for the same genes. You might recognize that you have one set of chromosomes from your mother and the remaining set from your father. Meiosis reduces the number of chromosomes to a haploid (1N) or single set. This reduction is significant because a cell with a haploid number of chromosomes can fuse with another haploid cell during sexual reproduction and restore the original, diploid number of chromosomes to the new individual. In addition to reducing the number of chromosomes, meiosis shuffles the genetic material so that each resulting cell carries a new and unique set of genes in a process of independent assortment.

As in mitosis, meiosis is preceded by replication of each chromosome to form two chromatids attached at a centromere. However, reduction of the chromosome number and production of new genetic combinations result from two events that don’t occur in mitosis. First, meiosis includes two rounds of chromosome separation. Chromosomes are replicated before the first round, but not before the second round. Thus, the genetic material is replicated once and divided twice. This produces half the original number of chromosomes.

Crossing over between chromatids of homologous chromosomes increases genetic diversity during meiosis I. Synapsis occurs during prophase I as the homologous chromosomes begin to pair up. Credit: Jeremy Seto (CC-BY-NC-SA)

Second, during an early stage of meiosis each chromosome (comprised of two chromatids) pairs along its length with its homolog. This pairing of homologous chromosomes results in a physical touching called synapsis, during which the four chromatids (a tetrad) exchange various segments of genetic material. This exchange of genetic material is called crossing-over and produces new genetic combinations. During crossing-over there is no gain or loss of genetic material. But afterward, each chromatid of the chromosomes contains different segments (alleles) that is exchanged with other chromatids.

Stages and Events of Meiosis

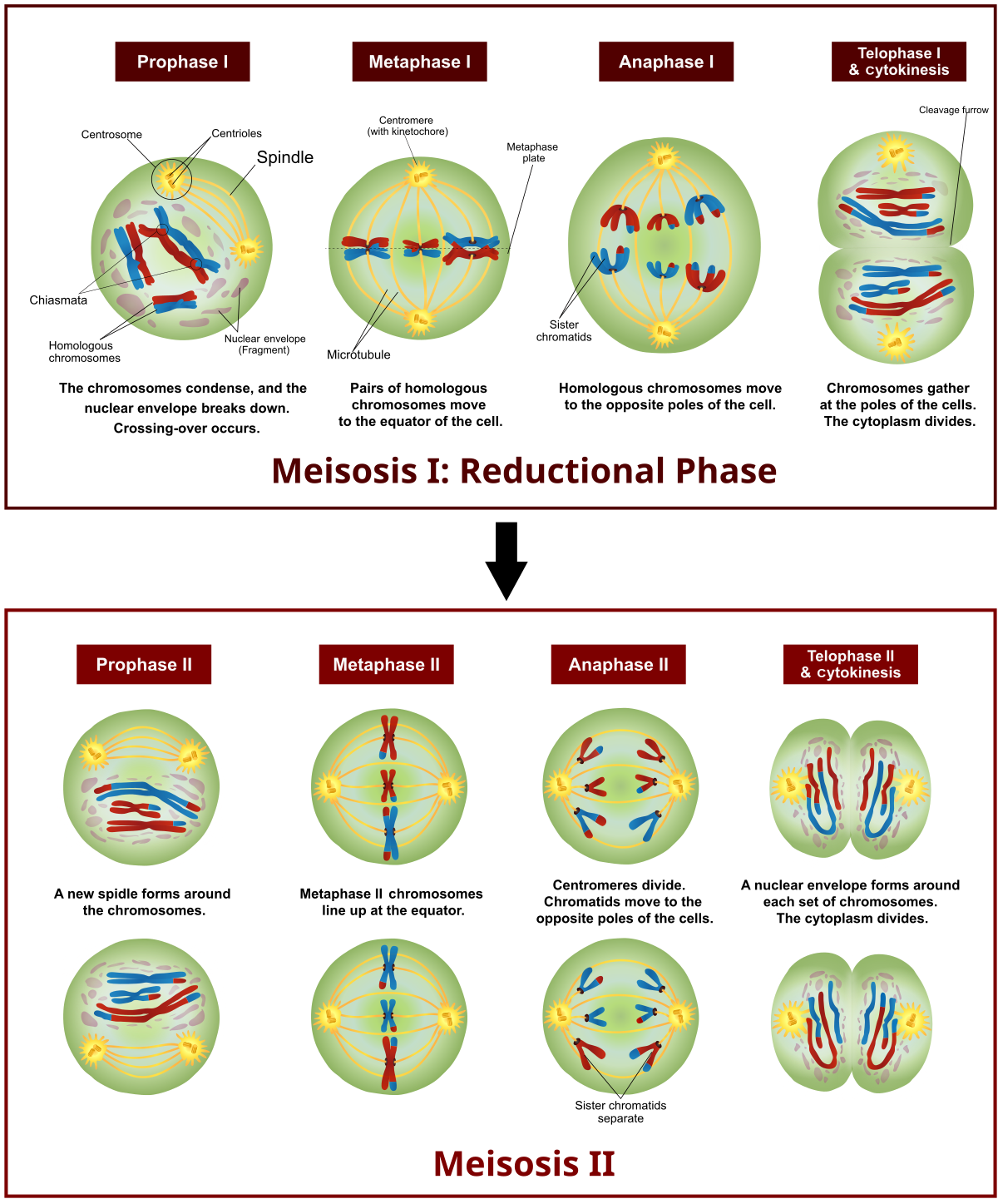

Stages of Meiosis. Credit: Ali Zifan (CC-BY 4.0)

Although meiosis is a continuous process, we can study it more easily by dividing it into stages just as we did for mitosis. Indeed, meiosis and mitosis are similar, and their corresponding stages of prophase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase have much in common. However, meiosis is longer than mitosis because meiosis involves two nuclear divisions instead of one. These two divisions are called Meiosis I and Meiosis II. The chromosome number is reduced (reductional division) during Meiosis I, and chromatids comprising each chromosome are separated in Meiosis II. Each division involves the events of prophase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase.

Advanced Video Overview of Meiosis

Oogenesis

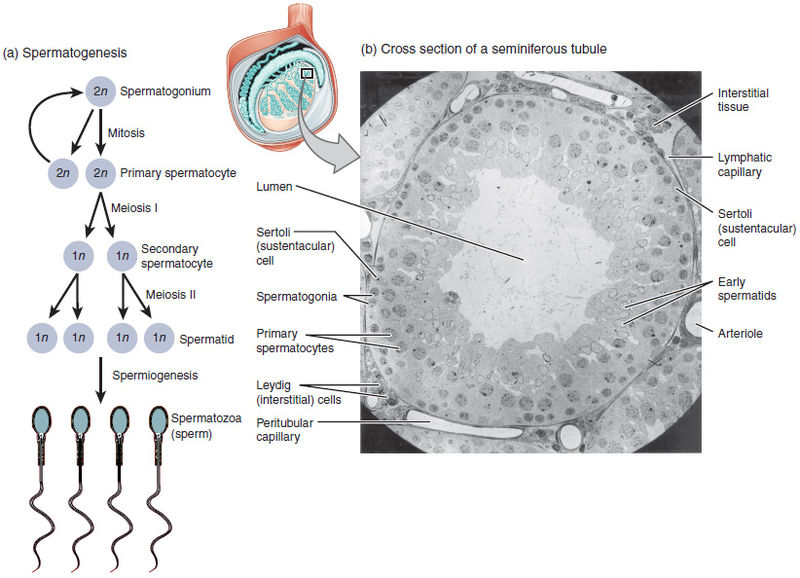

Spermatogenesis

Fertilization

| Summary of Cell Division | ||

| Mitosis | Meiosis | |

| Number of Cells at the Start | ||

| Number of Cells at the End | ||

| Number of Cell Divisions | ||

| Chromosome Number (N) | Start:______ End:______ |

Start:______ End:______ |

| Number of Chromosomes in the Cell at the Start of the Process (Human Cell) | ||

| Number of Chromosomes in the Cell at the End of the Process (Human Cell). | ||

| Daughter Cells (N or 2N) | ||

| Daughter Cell Genetics (Identical or Non-identical) | ||

| Purpose of Division | ||