2.2: The Atmosphere

- Page ID

- 79699

INTRODUCTION

The atmosphere, the gaseous layer that surrounds the earth, formed over four billion years ago. During the evolution of the solid earth, volcanic eruptions released gases into the developing atmosphere. Assuming the outgasing was similar to that of modern volcanoes, the gases released included: water vapor (H2O), carbon monoxide (CO), carbon dioxide (CO2), hydrochloric acid (HCl), methane (CH4), ammonia (NH3), nitrogen (N2) and sulfur gases. The atmosphere was reducing because there was no free oxygen. Most of the hydrogen and helium that outgassed would have eventually escaped into outer space due to the inability of the earth's gravity to hold on to their small masses. There may have also been significant contributions of volatiles from the massive meteoritic bombardments known to have occurred early in the earth's history.

Water vapor in the atmosphere condensed and rained down, eventually forming lakes and oceans. The oceans provided homes for the earliest organisms which were probably similar to cyanobacteria. Oxygen was released into the atmosphere by these early organisms, and carbon became sequestered in sedimentary rocks. This led to our current oxidizing atmosphere, which is mostly comprised of nitrogen (roughly 71 percent) and oxygen (roughly 28 percent). Water vapor, argon and carbon dioxide together comprise a much smaller fraction (roughly 1 percent). The atmosphere also contains several gases in trace amounts, such as helium, neon, methane and nitrous oxide. One very important trace gas is ozone, which absorbs harmful UV radiation from the sun.

ATMOSPHERIC STRUCTURE

The earth's atmosphere extends outward to about 1,000 kilometers where it transitions to interplanetary space. However, most of the mass of the atmosphere (greater than 99 percent) is located within the first 40 kilometers. The sun and the earth are the main sources of radiant energy in the atmosphere. The sun's radiation spans the infrared, visible and ultraviolet light regions, while the earth's radiation is mostly infrared.

The vertical temperature profile of the atmosphere is variable and depends upon the types of radiation that affect each atmospheric layer. This, in turn, depends upon the chemical composition of that layer (mostly involving trace gases). Based on these factors, the atmosphere can be divided into four distinct layers: the troposphere, stratosphere, mesosphere, and thermosphere.

The troposphere is the atmospheric layer closest to the earth's surface. It extends about 8 - 16 kilometers from the earth's surface. The thickness of the layer varies a few km according to latitude and the season of the year. It is thicker near the equator and during the summer, and thinner near the poles and during the winter. The troposphere contains the largest percentage of the mass of the atmosphere relative to the other layers. It also contains some 99 percent of the total water vapor of the atmosphere.

The temperature of the troposphere is warm (roughly 17º C) near the surface of the earth. This is due to the absorption of infrared radiation from the surface by water vapor and other greenhouse gases (e.g. carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide and methane) in the troposphere. The concentration of these gases decreases with altitude, and therefore, the heating effect is greatest near the surface. The temperature in the troposphere decreases at a rate of roughly 6.5º C per kilometer of altitude. The temperature at its upper boundary is very cold (roughly -60º C).

Because hot air rises and cold air falls, there is a constant convective overturn of material in the troposphere. Indeed, the name troposphere means “region of mixing.” For this reason, all weather phenomena occur in the troposphere. Water vapor evaporated from the earth's surface condenses in the cooler upper regions of the troposphere and falls back to the surface as rain. Dust and pollutants injected into the troposphere become well mixed in the layer, but are eventually washed out by rainfall. The troposphere is therefore self cleaning.

A narrow zone at the top of the troposphere is called the tropopause. It effectively separates the underlying troposphere and the overlying stratosphere. The temperature in the tropopause is relatively constant. Strong eastward winds, known as the jet stream, also occur here.

The stratosphere is the next major atmospheric layer. This layer extends from the tropopause (roughly 12 kilometers) to roughly 50 kilometers above the earth's surface. The temperature profile of the stratosphere is quite different from that of the troposphere. The temperature remains relatively constant up to roughly 25 kilometers and then gradually increases up to the upper boundary of the layer. The amount of water vapor in the stratosphere is very low, so it is not an important factor in the temperature regulation of the layer. Instead, it is ozone (O3) that causes the observed temperature inversion.

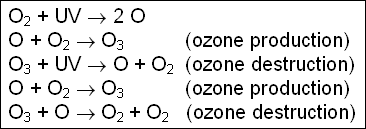

Most of the ozone in the atmosphere is contained in a layer of the stratosphere from roughly 20 to 30 kilometers. This ozone layer absorbs solar energy in the form of ultraviolet radiation (UV), and the energy is ultimately dissipated as heat in the stratosphere. This heat leads to the rise in temperature. Stratospheric ozone is also very important for living organisms on the surface of the earth as it protects them by absorbing most of the harmful UV radiation from the sun. Ozone is constantly being produced and destroyed in the stratosphere in a natural cycle. The basic reactions involving only oxygen (known as the "Chapman Reactions") are as follows:

The production of ozone from molecular oxygen involves the absorption of high energy UV radiation (UVA) in the upper atmosphere. The destruction of ozone by absorption of UV radiation involves moderate and low energy radiation (UVB and UVC). Most of the production and destruction of ozone occurs in the stratosphere at lower latitudes where the ultraviolet radiation is most intense.

Ozone is very unstable and is readily destroyed by reactions with other atmospheric species such nitrogen, hydrogen, bromine, and chlorine. In fact, most ozone is destroyed in this way. The use of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) by humans in recent decades has greatly affected the natural ozone cycle by increasing the rate of its destruction due to reactions with chlorine. Because the temperature of the stratosphere rises with altitude, there is little convective mixing of the gases. The stratosphere is therefore very stable. Particles that are injected (such as volcanic ash) can stay aloft for many years without returning to the ground. The same is true for pollutants produced by humans. The upper boundary of the stratosphere is known as the stratopause, which is marked by a sudden decrease in temperature.

The third layer in the earth's atmosphere is called the mesosphere. It extends from the stratopause (about 50 kilometers) to roughly 85 kilometers above the earth's surface. Because the mesosphere has negligible amounts of water vapor and ozone for generating heat, the temperature drops across this layer. It is warmed from the bottom by the stratosphere. The air is very thin in this region with a density about 1/1000 that of the surface. With increasing altitude this layer becomes increasingly dominated by lighter gases, and in the outer reaches, the remaining gases become stratified by molecular weight.

The fourth layer, the thermosphere, extends outward from about 85 kilometers to about 600 kilometers. Its upper boundary is ill defined. The temperature in the thermosphere increases with altitude, up to 1500º C or more. The high temperatures are the result of absorption of intense solar radiation by the last remaining oxygen molecules. The temperature can vary substantially depending upon the level of solar activity.

The lower region of the thermosphere (up to about 550 kilometers) is also known as the ionosphere. Because of the high temperatures in this region, gas particles become ionized. The ionosphere is important because it reflects radio waves from the earth's surface, allowing long-distance radio communication. The visual atmospheric phenomenon known as the northern lights also occurs in this region. The outer region of the atmosphere is known as the exosphere. The exosphere represents the final transition between the atmosphere and interplanetary space. It extends about 1000 kilometers and contains mainly helium and hydrogen. Most satellites operate in this region.

Solar radiation is the main energy source for atmospheric heating. The atmosphere heats up when water vapor and other greenhouse gases in the troposphere absorb infrared radiation either directly from the sun or re-radiated from the earth's surface. Heat from the sun also evaporates ocean water and transfers heat to the atmosphere. The earth's surface temperature varies with latitude. This is due to uneven heating of the earth's surface. The region near the equator receives direct sunlight, whereas sunlight strikes the higher latitudes at an angle and is scattered and spread out over a larger area. The angle at which sunlight strikes the higher latitudes varies during the year due to the fact that the earth's equatorial plane is tilted 23.5º relative to its orbital plane around the sun. This variation is responsible for the different seasons experienced by the non-equatorial latitudes.

WIND

Convecting air masses in the troposphere create air currents known as winds, due to horizontal differences in air pressure. Winds flow from a region of higher pressure to one of a lower pressure. Global air movement begins in the equatorial region because it receives more solar radiation. The general flow of air from the equator to the poles and back is disrupted, though, by the rotation of the earth. The earth's surface travels faster beneath the atmosphere at the equator and slower at the poles. This causes air masses moving to the north to be deflected to the right, and air masses moving south to be deflected to the left. This is known as the "Coriolis Effect." The result is the creation of six huge convection cells situated at different latitudes. Belts of prevailing surface winds form and distribute air and moisture over the earth.

Jet streams are extremely strong bands of winds that form in or near the tropopause due to large air pressure differentials. Wind speeds can reach as high as 200 kilometers per hour. In North America, there are two main jet streams: the polar jet stream, which occurs between the westerlies and the polar easterlies, and the subtropical jet stream, which occurs between the trade winds and the westerlies.

WEATHER

The term weather refers to the short term changes in the physical characteristics of the troposphere. These physical characteristics include: temperature, air pressure, humidity, precipitation, cloud cover, wind speed and direction. Radiant energy from the sun is the power source for weather. It drives the convective mixing in the troposphere which determines the atmospheric and surface weather conditions.

Certain atmospheric conditions can lead to extreme weather phenomena such as thunderstorms, floods, tornadoes and hurricanes. A thunderstorm forms in a region of atmospheric instability, often occurring at the boundary between cold and warm fronts. Warm, moist air rises rapidly (updraft) while cooler air flows down to the surface (downdraft). Thunderstorms produce intense rainfall, lightning and thunder. If the atmospheric instability is very large and there is a large increase in wind strength with altitude (vertical wind shear), the thunderstorm may become severe. A severe thunderstorm can produce flash floods, hail, violent surface winds and tornadoes.

Floods can occur when atmospheric conditions allow a storm to remain in a given area for a length of time, or when a severe thunderstorm dumps very large amounts of rainfall in a short time period. When the ground becomes saturated with water, the excess runoff flows into low-lying areas or rivers and causes flooding.

A tornado begins in a severe thunderstorm. Vertical wind shear causes the updraft in the storm to rotate and form a funnel. The rotational wind speeds increase and vertical stretching occurs due to angular momentum. As air is drawn into the funnel core, it cools rapidly and condenses to form a visible funnel cloud. The funnel cloud descends to the surface as more air is drawn in. Wind speeds in tornadoes can reach several hundred miles per hour. Tornadoes are most prevelant in the Great Plains region of the United States, forming when cold dry polar air from Canada collides with warm moist tropical air from the Gulf of Mexico.

A cyclone is an area of low pressure with winds blowing counter-clockwise (Northern Hemisphere) or clockwise (Southern Hemisphere) around it. Tropical cyclones are given different names depending on their wind speed. The strongest tropical cyclones in the Atlantic Ocean (wind speed exceeds 74 miles per hour) are called hurricanes. These storms are called typhoons (Pacific Ocean) or cyclones (Indian Ocean) in other parts of the world. Hurricanes are the most powerful of all weather systems, characterized by strong winds and heavy rain over wide areas. They form over the warm tropical ocean and quickly lose intensity when they move over land. Hurricanes affecting the continental United States generally occur from June through November.

OCEAN CURRENTS

The surface of the earth is over 71 percent water, so it is not surprising that oceans have a significant effect on the weather and climate. Because of the high heat capacity of water, the ocean acts as a temperature buffer. That is why coastal climates are less extreme than inland climates. Most of the radiant heat from the sun is absorbed by ocean surface waters and ocean currents help distribute this heat.

Currents are the movement of water in a predictable pattern. Surface ocean currents are driven mostly by prevailing winds. The "Coriolis Effect" causes the currents to flow in circular patterns. These currents help transport heat from the tropics to the higher latitudes. Two large surface currents near the United States are the California current along the west coast and the Gulf Stream along the east coast. Deep ocean currents are driven by differences in water temperature and density. They move in a convective pattern.

The less dense (lower salinity) warm water in the equatorial regions rises and moves towards the polar regions, while more dense (higher salinity) cold water in the polar regions sinks and moves towards the equatorial regions. Sometimes this cold deep water moves back to the surface along a coastline in a process known as upwelling. This cold deep water is rich in nutrients that support productive fishing grounds.

About every three to seven years, warm water from the western equatorial Pacific moves to the eastern equatorial Pacific due to weakened trade winds. The eastern Pacific Ocean thus becomes warmer than usual for a period of about a year. This is known as El Niño. El Niño prevents the nutrient-rich, cold-water upwellings along the western coast of South America. It also impacts the global weather conditions. Some regions receive heavier than usual rainfall, while other regions suffer drought conditions with lower than usual rainfall.

Probably the most important part of weather is precipitation as rainfall or snowfall. Water from the vast salty oceans evaporates and falls over land as fresh water. It is rainfall that provides fresh water for land plants, and land animals. Winter snowfall in mountainous regions provides a stored supply of fresh water which melts and flows into streams during the spring and summer.

Atmospheric clouds are the generators of precipitation. Clouds form when a rising air mass cools and the temperature and humidity are right for condensation to occur. Condensation does not occur spontaneously, but instead requires a condensation nuclei. These are tiny (less than 1µm) dust or smoke particles. The condensation droplet is small enough (about 20 µm) that it is supported by the atmosphere against the pull of gravity. The visible result of these condensation droplets is a cloud.

Under the right conditions, droplets may continue to grow by continued condensation onto the droplet and/or coalescence with other droplets through collisions. When the droplets become sufficiently large they begin to fall as precipitation. Typical raindrops are about 2 mm in diameter. Depending upon the temperature of the cloud and the temperature profile of the atmosphere from the cloud to the earth's surface, various types of precipitation can occur: rain, freezing rain, sleet or snow. Very strong storms can produce relatively large chunks of ice called hailstones.

CLIMATE

Climate can be thought of as a measure of a region's average weather over a period of time. In defining a climate, the geography and size of the region must be taken into account. A micro-climate might involve a backyard in the city. A macroclimate might cover a group of states. When the entire earth is involved, it is a global climate. Several factors control large scale climates such as latitude (solar radiation intensity), distribution of land and water, pattern of prevailing winds, heat exchange by ocean currents, location of global high and low pressure regions, altitude and location of mountain barriers.

The most widely used scheme for classifying climate is the Köppen System. This scheme uses average annual and monthly temperature and precipitation to define five climate types:

| 1. | tropical moist climates: average monthly temperature is always greater than 18°C |

| 2. | dry climates: deficient precipitation most of the year |

| 3. | moist mid-latitude climates with mild winters |

| 4. | moist mid-latitude climates with severe winters |

| 5. | polar climates: extremely cold winters and summers. |

Using the Köppen system and the seasonal dominance of large scale air masses (e.g., maritime or continental), the earth's climate zones can be grouped as follows:

| 1. | tropical wet |

| 2. | tropical wet and dry |

| 3. | tropical desert |

| 4. | mid-latitude wet |

| 5. | mid-latitude dry summer |

| 6. | mid-latitude dry winter |

| 7. | polar wet |

| 8. | dry and polar desert |

Los Angeles has a mid-latitude dry summer climate, whereas New Orleans has a mid-latitude wet climate.

Data from natural climate records (e.g. ocean sediments, tree rings, Antarctic ice cores) show that the earth's climate constantly changed in the past, with alternating periods of colder and warmer climates. The most recent ice age ended only about 10,000 years ago. The natural system controlling climate is very complex. It consists of a large number of feedback mechanisms that involve processes and interactions within and between the atmosphere, biosphere and the solid earth.

Some of the historical causes of global climate change include plate tectonics (landmass and ocean current changes), volcanic activity (atmospheric dust and greenhouse gases), and long-term variations in the earth's orbit and the angle of its rotation axis (absolute and spatial variations in solar radiation).

More recently, anthropogenic (human) factors are known to be changing the global climate. Since the late 19th century, the average temperature of the earth has increased about 1º C. This warming trend is the result of the increased release of greenhouse gases (e.g., CO2) into the atmosphere from the combustion of fossil fuels. More on the science of climate change will be covered in an upcoming section but it will radically transform the physical and biological nature of our planet if we do not address the root causes of climate change now. /p>