2.6: Endospore Stain

- Page ID

- 149771

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Describe what an endospore/spore is and why they are important for the bacterial species that form them.

- Identify/give examples of environmental conditions that can stimulate spore formation.

- Tell that Bacillus species and Clostridium species can be clinically important endospore-forming species.

- Compare and contrast "vegetative cell" and "spore."

- Successfully conduct an endospore stain.

- Interpret results of an endospore stain.

- Identify when endospores are terminal, subterminal, and central in microscopic images, diagrams, and descriptions.

- Tell how the endospore stain works including the stains involved and how the stains penetrate cells and do or do not wash out of cells.

- Apply the concept of bacterial endospores to healthcare settings and how spores can make treatment of infections by spore-forming species challenging.

- Tell that endospores are only produced by only some bacterial species, and therefore their presence/absence can be useful in identifying bacterial species.

Endospores

An endospore is a form of a bacterial cell. Only some species of bacteria can produce endospores. Endospores are made so the cell can survive poor growth or poor survival conditions. An endospore is a mainly inactive version of a cell that is analagous to a survival bunker. When environmental conditions are poor, or even deadly, bacteria that are able to will produce endospores to survive. When environmental conditions improve, endospores can produce the active cells again (active cells are called vegetative cells.) Bacterial endospores are the most resistant structures of all living organisms, and they can live in this dormant dehydrated state for hundreds of years (even some documented at thousands of years). The stimulus that triggers sporulation (formatio of spores) can vary and may include nutrient depletion, desiccation, chemicals, heat, etc.

Endospores are not for reproduction. One spore forms inside of one vegetative cell (vegetative = metabolically active cell). When environmental conditions improve, one spore germinates to produce one vegetative cell.

Endospore production is a very important characteristic of some bacteria, allowing them to resist adverse environmental conditions such as desiccation, chemical exposure, extreme heat, etc. Endospores were first identified in the 1800s (John Tyndall developed a process for destroying them with an intermittent heating procedure), although the stain procedures to identify them did not develop until the early twentieth century.

The identification of endospores is very important for the clinical microbiologist who is analyzing a patient's body fluid or tissue since there are not that many spore-forming genera. Knowing if the species of bacteria causing an infection forms spores or not helps to narrow down the possible bacterial species causing the infection. In fact, there are two major pathogenic (disease-causing) spore-forming genera: Bacillus and Clostridium. Bacillus and Clostridium species cause a number of dangerous and lethal diseases such as botulism, gangrene, tetanus, c-diff, and anthrax, to name a few.

Some bacteria have to be put into unfavorable situations (high cell density and starvation are two key triggers) to go into sporulation. Other species will make spores easily without much provocation (e.g. Bacillus subtilis). Vegetative cells that have not yet made spores may be in the process of making the spore or will not make them at all. The vegetative cell is metabolically active, whereas the spore is not. The location where an endospore is within a vegetative cell is also useful for distinguishing bacterial species. Endospores may be located in a terminal (end of the cell), subterminal (near the end of the cell), or central (middle of the cell) position. A particular species of the genus will form spores in a specific area, producing another useful taxonomic identification tool and therefore useful in identifying the species of bacteria.

Endospore Stain

The endospore stain is a differential stain that enables visualization of endospores and differentiation of spores from vegetative cells. The primary stain, malachite green, is a relatively weakly binding stain that attaches to the cell wall of vegetative cells and the spore wall of endospores and mature spores. In fact, if washed well with water, the stain comes right out of the cell walls of vegetative cells. In contrast, malachite green will not wash from the spore wall. Once the stain is in the spore wall, it is locked in and will not wash out. This is why there does not need to be a decolorizer in this stain procedure.

It is difficult to stain the tough spores. Heat is used to enable the malachite green to penetrate the low-permeability spore walls. A variety of chemicals make up the spore wall (keratin protein, calcium), but deeper in the wall is peptidoglycan. The keratin forming the outer portion of the endospore wall resists stain. Heating the cells will make the spore wall more permeable to the malachite green so it can then attach to the peptidoglycan. Once in, the malachite green will not come out because the overlying spore wall becomes less permeable when the smear cools.

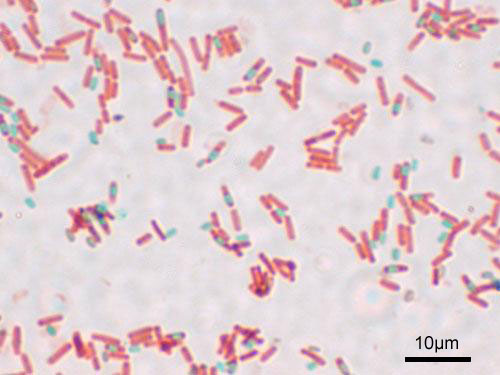

When the malachite green is washed out of the vegetative cells they become transparent. A counterstain, safranin, is used to stain the vegetative cells pink. The result is endospores that appear green and vegetative cells that appear pink.

Laboratory Instructions

Prepare a Bacterial Smear

You may find it helpful to draw a circle (wax pencil is best) on the opposite side of the slide where you will spread your smear. This will help you later in locating the smear. The wax pencil is better than a marker because it will not wash off easily from the glass.

If you are using a liquid culture, gently mix the culture until you get an even, cloudy mixture (it should look somewhat like skim milk). If you mix too aggressively, you will lose the bacterial morphology.

- Prepare a bacterial smear on the slide:

- If you are taking bacteria from a solid culture (slant or petri plate), place a small drop (only 1 drop) of saline, deionized (DI) water, or distilled water onto a microscope slide and use a loop to aseptically add bacteria to the water (avoid taking a large chunk of bacteria since the cells will be too dense to view individual cells). Use the loop to spread the bacteria in the water drop and to spread the water drop out to make it thinner (it will dry faster).

- If you are taking a bacteria from a a liquid culture (broth), place 1 or 2 loopfuls of bacteria directly onto a microscope slide (no saline or water added).

- Allow the slide(s) to air dry on the slide warmer (or air dry if a slide warmer is not available).

Heat Fix the Bacterial Smear

Once the liquid has completely evaporated on the surface of the slide, heat fix by passing the slide:

Attach a wooden clip to the microscope slide to hold it.

- Pass the underside of the microscope slide through a flame three times.

- Allow the slide to cool and then continue with your staining protocol.

If you heat fix too little, the bacteria will wash off the slide. If you heat fix too much, you will cook the bacteria and denature them.

Endospore Stain

- Put a beaker of water on the hot plate and boil until steam is coming up from the water.

- Turn the hot plate heat down so that the water is barely boiling.

- Place a wire stain rack over the beaker. Steam should be coming up through the wire rack.

- Cut a small piece of paper towel and place it on top of the smear on the slide. The towel will keep the dye from evaporating too quickly, thereby giving more contact time between the dye and the bacterial walls.

- Flood the smear with the primary dye, malachite green, and leave for 5 minutes. Keep the paper towel moist with the malachite green. DO NOT let the dye dry on the towel.

- Remove and discard the small paper towel piece.

- Wash the slide really well with water.

- Move the slide off the wire rack. The next steps are done without the steam of the hot water.

- Use a wooden clip and attach it to the slide and put the slide over a small chemical waste bucket.

- Apply safranin to the smear and leave for 1 minute.

- Wash the slide well with water allowing the water to run off the slide into the bucket.

- Blot the dry (do not wipe) with bibulous paper.

- Place the stained slide on a microscope and examine. Be sure to begin at the lowest power (look for the pink and green colors of the stains). Focus at lowest power and then increase one objective magnification at a time.

CARMEN QUESTIONS - Endospore Stain

- The species of bacteria you stained is Bacillus subtilis. Based on the results of your endospore stain, does Bacillus subtilis form endospores? How can you tell?

- What color are the vegetative cells in the endospore stain?

- Why might a species of bacteria form endospores? What is the advantage of forming spores for bacteria?

- Why might infections with species of bacteria that produce spores be more difficult to treat in a healthcare setting than species of bacteria that do not produce spores?

Attributions

- Bacillus subtilis Spore.jpg by Y tambe is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

- Chapter Image: OSC Microbio 02 04 Endospores.jpg by CNX OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0

- Endospore Bazillus.jpg by Geoman3 is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

- Endospore Formation.png by Farah, Sophia, Alex is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

- Microbiology Labs I by Delmar Larsen and Jackie Reynolds is licensed under an undeclared license.