1.6: Fungal Parasites

- Page ID

- 149764

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Define and differentiate between yeast and mold.

- Define, identify, and apply the following terms: budding, hyphae, mycelium, septate, coenocytic, sporangium, sporangiophore, sporangiospore, conidia, conidiophore, vesicle

- Describe how Aspergillus can cause infection in humans, the risk factors for aspergillosis, and the symptoms of infection.

- Describe how Coccidioides can cause infection in humans, the risk factors for infection, and the symptoms of infection.

- Give both the medical and common names for Coccidioides infections.

- Tell that antibiotics cannot be used to treat fungal infections and that they must be treated with antifungal medications.

Introduction to Fungi

Mycology is the study of fungi. Fungi are eukaryotic organisms which grow as either yeast or mold. However, there are some fungi that are dimorphic, meaning they can grow as yeast under certain environmental conditions (such as the warm moist lungs in the body) and mold under other conditions (such as in soil in the environment). For example, Coccidioides immitis, the fungus responsible for San Joaquin Valley Fever, is an example of a dimorphic fungus.

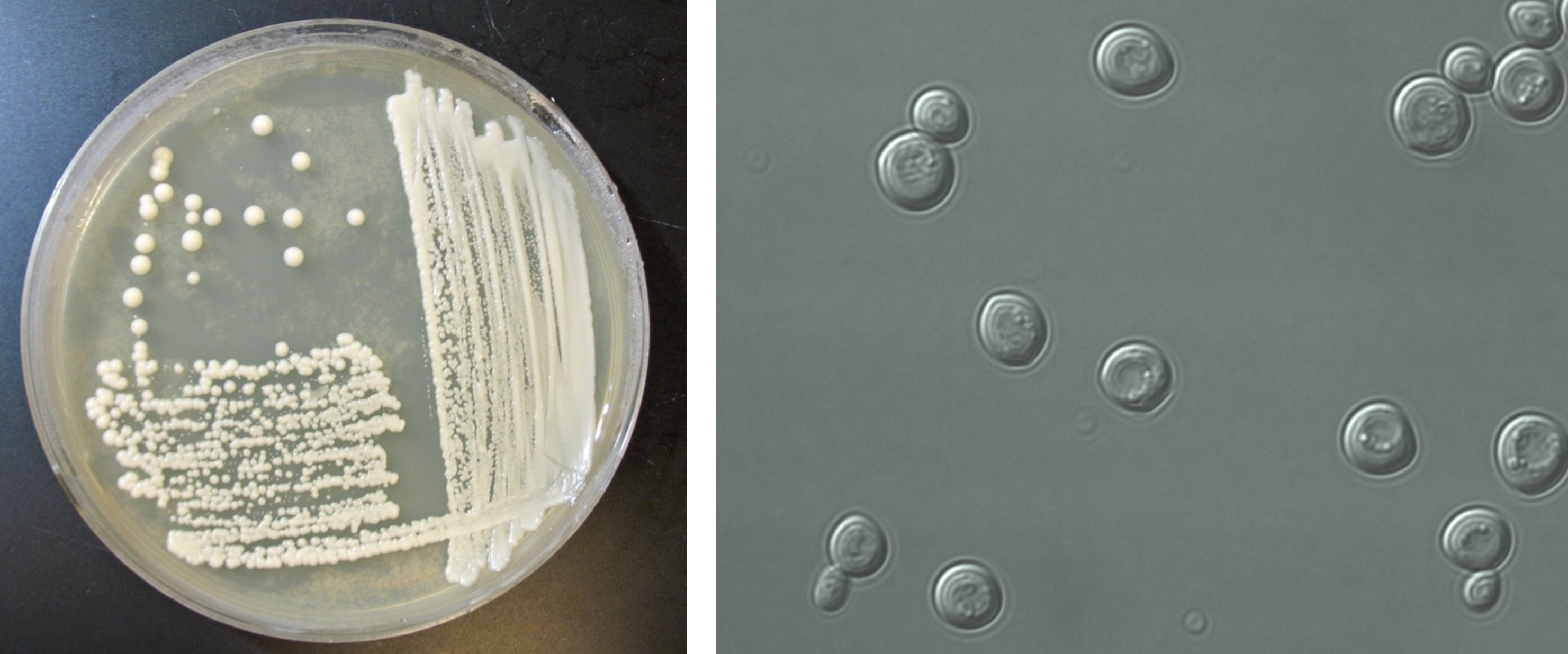

Fungi grow slower than bacteria and at a lower temperature and lower pH than most bacteria prefer. Sabouraud’s agar is selective media for fungi because it incorporates simple nutrients (glucose and peptone) at a pH of 4.5-5.6 which inhibits bacterial growth. Although some yeasts can grow at 36°C, we incubate all fungal cultures at 25 to 30°C for at least one week. Some fungi take three weeks or more to grow.

Yeast

The colonial appearance of most yeast is moist, creamy and white in color and similar in appearance to Staphylococcus colonies. Microscopically, yeast cells are unicellular and round to oval, whereas bacteria cells vary in shape (cocci, rods, spirals). Yeast cells are usually five to ten times larger than bacteria and can be visualized at 400X total magnification. Yeast reproduce asexually by budding and the newly produced cell, called a bud or blastospore, protrudes from the periphery of the parent cell. The blastospore may break off from the parent cell or stay attached. Successive blastospores remaining attached to the original cell result in the formation of pseudohyphae.

Most yeast have similar macroscopic and microscopic appearances. Biochemical tests, such as carbohydrate assimilation tests, must be performed to identify yeast species. Examples of yeast include Candida albicans which is an opportunistic pathogen (thrush, diaper rash, vaginal yeast infections) and Saccharomyces cerevisiae which is used to make bread, beer, and wine.

Mold

Fungi that grow as mold produce multicellular filaments called hyphae (plural) or hypha (singular). Most species of mold hyphal filaments are separated by a cross wall (septum) and are called septate hyphae. In mold species where the hyphal filaments not separated by cross walls are called aseptate or coencocytic hyphae. Hyphal filaments intertwined into a mass, known as mycelia (plural) or mycelium (singular), can be seen macroscopically as fuzzy or hairy, colorful colonies. Some of the hyphae, called vegetative hyphae, grow on or down into the agar surface to extract nutrients from the medium. Other hyphae, called aerial hyphae, grow above the agar surface and produce asexual reproductive spores.

The two types of asexual spores produced by molds are called sporangiospores and conidiospores. Sporangiospores are produced at the end of aerial hyphae called sporangiophores in a saclike structure called a sporangium. The sporangia of specific molds have characteristic shapes which can be used to identify the mold species. An example of a mold that produces sporangiospores is the bread mold, Rhizopus. Conidiospores are formed on aerial hyphae called conidiophores. Conidia may be one-celled (microconidia) or multicelled (macroconidia). Examples of fungi that produce conidiospores are Penicillium and Aspergillus.

Molds are usually identified in the laboratory by their characteristic macroscopic appearance, hyphal structure (septate or nonseptate) and type of asexual sporulation. Since spore formation is an important identification criterion, slide cultures are performed to observe sporulation without disturbing the hyphal structures.

Aspergillus

Introduction to Aspergillus (Cause of Aspergillosis)

Aspergillosis is an infection caused by Aspergillus, a common mold (a type of fungus) that lives indoors and outdoors. Most people breathe in Aspergillus spores every day without getting sick. However, people with weakened immune systems or lung diseases are at a higher risk of developing health problems due to Aspergillus. The types of health problems caused by Aspergillus include allergic reactions, lung infections, and infections in other organs.

There are approximately 180 species of Aspergillus, but fewer than 40 of them are known to cause infections in humans. Aspergillus fumigatus is the most common cause of human Aspergillus infections. Other common species include A. flavus, A. terreus, and A. niger.

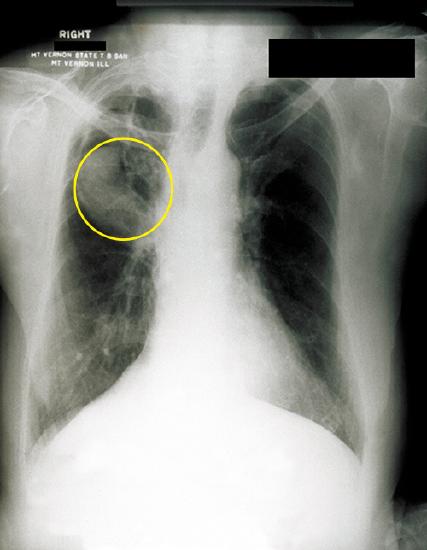

Healthcare providers consider your medical history, risk factors, symptoms, physical examinations, and lab tests when diagnosing aspergillosis. Imaging tests such as a chest x-ray or a CT scan a patient's lungs or other parts of the body depending on the location of the suspected infection. If a healthcare provider suspects an Aspergillus infection in the lungs, they might collect a sample of fluid from your respiratory tract to send to a laboratory. Healthcare providers may also perform a tissue biopsy, in which a small sample of affected tissue is analyzed in a laboratory for evidence of Aspergillus under a microscope or in a fungal culture. A blood test can help diagnose invasive aspergillosis early in people who have severely weakened immune systems.

Types of Aspergillosis

- Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA): Occurs when Aspergillus causes inflammation in the lungs and allergy symptoms such as coughing and wheezing, but doesn’t cause an infection.2

- Allergic Aspergillus sinusitis: Occurs when Aspergillus causes inflammation in the sinuses and symptoms of a sinus infection (drainage, stuffiness, headache) but doesn’t cause an infection.3

- Azole-Resistant Aspergillus fumigatus: Occurs when one species of Aspergillus, A. fumigatus, becomes resistant to certain medicines used to treat it. Patients with resistant infections might not get better with treatment.

- Aspergilloma: Occurs when a ball of Aspergillus grows in the lungs or sinuses, but usually does not spread to other parts of the body.4 Aspergilloma is also called a “fungus ball.”

- Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis: Occurs when Aspergillus infection causes cavities in the lungs, and can be a long-term (3 months or more) condition. One or more fungal balls (aspergillomas) may also be present in the lungs.5

- Invasive aspergillosis: Occurs when Aspergillus causes a serious infection, and usually affects people who have weakened immune systems, such as people who have had an organ transplant or a stem cell transplant. Invasive aspergillosis most commonly affects the lungs, but it can also spread to other parts of the body.

- Cutaneous (skin) aspergillosis: Occurs when Aspergillus enters the body through a break in the skin (for example, after surgery or a burn wound) and causes infection, usually in people who have weakened immune systems. Cutaneous aspergillosis can also occur if invasive aspergillosis spreads to the skin from somewhere else in the body, such as the lungs.6

Clinical Presentation: Aspergillus

The different types of aspergillosis can cause different symptoms.1

The symptoms of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) are similar to asthma symptoms, including:

- Wheezing

- Shortness of breath

- Cough

- Fever (in rare cases)

Symptoms of allergic Aspergillus sinusitis2 include:

- Stuffiness

- Runny nose

- Headache

- Reduced ability to smell

Symptoms of an aspergilloma (“fungus ball”)3 include:

- Cough

- Coughing up blood

- Shortness of breath

Symptoms of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis4,5 include:

- Weight loss

- Cough

- Coughing up blood

- Fatigue

- Shortness of breath

Invasive aspergillosis1 usually occurs in people who are already sick from other medical conditions, so it can be difficult to know which symptoms are related to an Aspergillus infection. However, the symptoms of invasive aspergillosis in the lungs include:

- Fever

- Chest pain

- Cough

- Coughing up blood

- Shortness of breath

- Other symptoms can develop if the infection spreads from the lungs to other parts of the body.

Laboratory Instructions: Aspergillus

- Examine Aspergillus using a microscope.

- Identify the following features:

- "hyphae" or "hypha"

- "conidiophore"

- "vesicle"

- "conidia (spores)" or "conidiospores"

CARMEN QUESTIONS: Aspergillus

- What areas of the human body can become infected with Aspergillus?

- Where does Aspergillus live and how are humans exposed to Aspergillus?

- Who populations are most at risk of developing aspergillosis?

- What is the difference between a mold and yeast?

- Is Aspergillus a mold or a yeast?

- Name the Aspergillus structures that branch from the hyphae to produce asexual spores?

- What are the Aspergillus asexual spores called?

- Can aspergillosis be treated with antibiotics? Explain your answer.

Coccidioides (Causes Coccidioidomycosis aka Valley Fever)

Introduction to Coccidioides (Cause of Coccidioidomycosis aka Valley Fever)

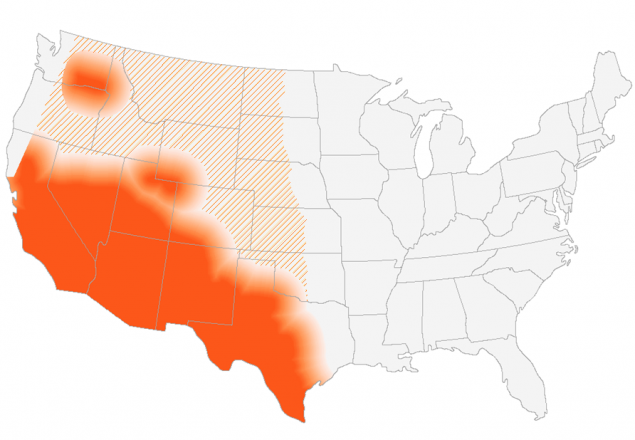

Valley fever is an infection caused by a fungus that lives in the soil. About 20,000 cases are reported in the United States each year, mostly from Arizona and California, and the number of cases is increasing. Valley fever can be misdiagnosed because its symptoms are similar to those of other respiratory illnesses. Here are some important things to know about Valley fever, also called coccidioidomycosis.

The fungus that causes Valley fever, Coccidioides, is found in soil in the southwestern United States, parts of Mexico and Central America, and parts of South America. It has also been found in south-central Washington State. The fungus might also live in similar areas with hot, dry climates. People can get Valley fever by breathing in the microscopic fungus from the air in these areas. Valley fever does not spread from person to person.

In areas where Valley fever is common, it’s difficult to completely avoid exposure to the fungus because it is in the environment. There is no vaccine to prevent infection. That’s why knowing about Valley fever is one of the most important ways to avoid delays in diagnosis and treatment. People who have symptoms of Valley fever and live in, work in, or have visited an area where the fungus is common should ask their doctor to test them for Valley fever. Healthcare providers should be aware that Valley fever symptoms are similar to those of other respiratory illnesses and should consider testing for Valley fever in patients with pneumonia symptoms who live in or have traveled to an area where Coccidioides lives.

The Financial Cost of Valley Fever

Valley fever is a serious, costly illness:

- Nearly 75% of people with Valley fever miss work or school

- As many as 40% of people who get Valley fever are hospitalized

- The average cost of a hospital stay for a person with Valley fever is almost $50,000

- About 60–80% of patients with Valley fever are given one or more rounds of antibiotics before receiving a correct diagnosis and appropriate treatment (antifungal medication is required for treatment)

Clinical Presentation of Coccidioides (Cause of Coccidioidomycosis aka Valley Fever)

Many people who are exposed to the fungus never have symptoms. Other people may have symptoms that include:

- Fatigue (tiredness)

- Cough

- Fever

- Shortness of breath

- Headache

- Night sweats

- Muscle aches or joint pain

- Rash on upper body or legs

The symptoms of valley fever can be similar to those of other respiratory illnesses, which may cause delays in diagnosis and treatment. For many people, symptoms go away within weeks or months without any treatment. But healthcare providers may prescribe antifungal medicine for some people to reduce symptoms or prevent the infection from getting worse. People who have severe lung infections or infections that have spread to other parts of the body always need antifungal treatment and may need to stay in the hospital.

Anyone can get Valley fever if they live in, work in, or travel to an area where the fungus lives in the environment. Valley fever can affect people of any age, but it’s most common in adults aged 60 and older. Also, certain groups of people may be at higher risk for developing the severe forms of valley fever, such as:

- People who have weakened immune systems, which may include people who:

- Have HIV

- Have had an organ transplant

- Are taking medications such as corticosteroids or tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors

- Pregnant people

- People who have diabetes

- People who are Black or Filipino

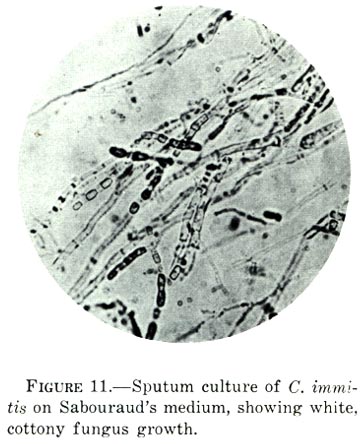

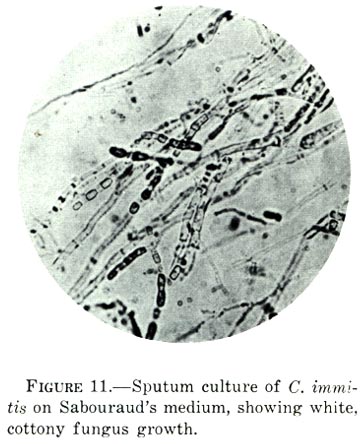

Laboratory Instructions: Coccidioides (Cause of Coccidioidomycosis aka Valley Fever)

- Carefully examine the microscopic image of Coccidioides in the image above.

CARMEN QUESTIONS: Coccidioides (Cause of Coccidioidomycosis aka Valley Fever)

- Based in careful examination of the microscopic image of Coccidioides, is this fungus growing as yeast or mold?

- Label the image above to show the location of "hyphae."

- Are the hyphae of Coccidioides septate or coenocytic? How can you tell?

- How do people become exposed to Coccidioides?

- Give the common name and the medical term for infection with Coccidioides.

- What populations are at greater risk of infection by Coccidioides?

- What are common symptoms of infection by Coccidioides?

- Where geographically can patients become develop coccidioidomycosis?

- What percentage of people with coccidioidomycosis become hospitalized?

- Do patients with a Coccidioides infection struggle to get a correct diagnosis?

- When should a healthcare professional consider coccidioidomycosis as a possible diagnosis?

- Can Coccidioides infection be treated with antibiotics? Explain your answer.

Attributions

- 20100815 1818 Mold.jpg by Bob Blaylock is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

- Aspergillus.jpg by US Department of Health and Human Services is in the public domain

- Valley Fever by California Department of Public Health is in the public domain

- Centers for Disease Control. "Aspergillosis.” In the public domain. Use of CDC material, including any links to the materials on the CDC, ATSDR or HHS websites, does not imply endorsement by CDC, ATSDR, HHS or the United States Government of this page, this textbook, the author, or the institution. The material is otherwise available on the agency website for no charge.

- Centers for Disease Control. "Valley Fever (Coccidiomycosis).” In the public domain. Use of CDC material, including any links to the materials on the CDC, ATSDR or HHS websites, does not imply endorsement by CDC, ATSDR, HHS or the United States Government of this page, this textbook, the author, or the institution. The material is otherwise available on the agency website for no charge.

- Coccidioides immitis on Sabouraud's medium.jpg by US Army is in the public domain

- Microbiology by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0

- Red Mountain Microbiology by Jill Raymond Ph.D.; Graham Boorse, Ph.D.; and Anne Mason M.S. is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

- Sporangium, sporangiospores, columella, sporangiophore or aerial hyphae of Mucor.jpg by Ajay Kumar Chaurasiya is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

- Yeast Photo 06.tif by Gustavo.leite is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0