21.1: What is Landscape Ecology?

- Page ID

- 78341

Landscape Ecology

Landscape ecology is the science of studying and improving relationships between ecological processes in the environment and particular ecosystems. This is done within a variety of landscape scales, development spatial patterns, and organizational levels of research and policy.[1][2][3] Concisely, landscape ecology can be described as the science of landscape diversity as the synergetic result of biodiversity and geodiversity.[4]

As a highly interdisciplinary field in systems science, landscape ecology integrates biophysical and analytical approaches with humanistic and holistic perspectives across the natural sciences and social sciences. Landscapes are spatially heterogeneous geographic areas characterized by diverse interacting patches or ecosystems, ranging from relatively natural terrestrial and aquatic systems such as forests, grasslands, and lakes to human-dominated environments including agricultural and urban settings.[2][5][6]

The most salient characteristics of landscape ecology are its emphasis on the relationship among pattern, process and scale, and its focus on broad-scale ecological and environmental issues. These necessitate the coupling between biophysical and socioeconomic sciences. Key research topics in landscape ecology include ecological flows in landscape mosaics, land use and land cover change, scaling, relating landscape pattern analysis with ecological processes, and landscape conservation and sustainability.[7] Landscape ecology also studies the role of human impacts on landscape diversity in the development and spreading of new human pathogens that could trigger epidemics.[8][9]

Heterogeneity is the measure of how parts of a landscape differ from one another. Landscape ecology looks at how this spatial structure affects organism abundance at the landscape level, as well as the behavior and functioning of the landscape as a whole. This includes studying the influence of pattern, or the internal order of a landscape, on process, or the continuous operation of functions of organisms.[11] Landscape ecology also includes geomorphology as applied to the design and architecture of landscapes.[12] Geomorphology is the study of how geological formations are responsible for the structure of a landscape.

History

Terminology

The German term Landschaftsökologie–thus landscape ecology–was coined by German geographer Carl Troll in 1939.[10] He developed this terminology and many early concepts of landscape ecology as part of his early work, which consisted of applying aerial photograph interpretation to studies of interactions between environment and vegetation.

Evolution of theory

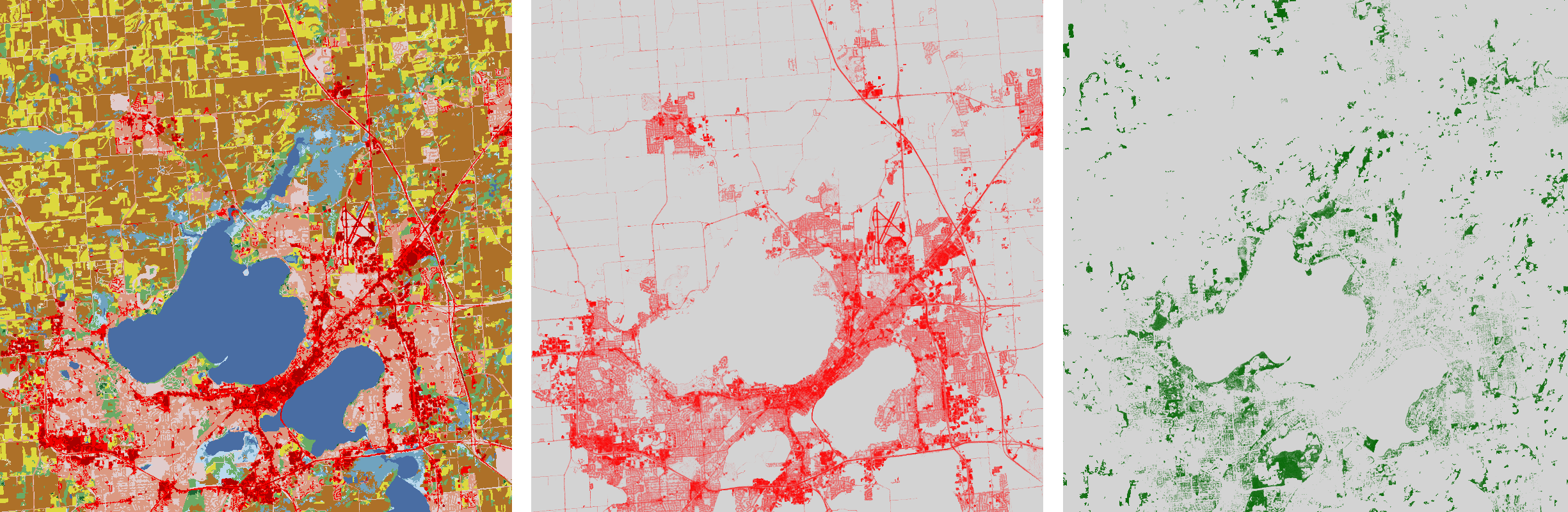

One central landscape ecology theory originated from MacArthur & Wilson's The Theory of Island Biogeography (see 21.4: Island Biogeography). This work considered the biodiversity on islands as the result of competing forces of colonization from a mainland stock and stochastic extinction. The concepts of island biogeography were generalized from physical islands to abstract patches of habitat by Levins' metapopulation model (which can be applied e.g. to forest islands in the agricultural landscape[13]). A metapopulation is a group of smaller populations of an organism in distinct habitat patches or islands which have individuals moving between patches. This generalization spurred the growth of landscape ecology by providing conservation biologists a new tool to assess how habitat fragmentation affects population viability. Recent growth of landscape ecology owes much to the development of geographic information systems (GIS)[14] and the availability of large-extent habitat data (e.g. remotely sensed datasets) Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\).

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Land cover surrounding Madison, WI. Left: fields are colored yellow and brown, water is colored blue, and urban surfaces are colored red. Center: impervious surfaces. Right: canopy cover.

Development as a discipline

Landscape ecology developed in Europe from historical planning on human-dominated landscapes. Concepts from general ecology theory were integrated in North America. While general ecology theory and its sub-disciplines focused on the study of more homogenous, discrete community units organized in a hierarchical structure (typically as ecosystems, populations, species, and communities), landscape ecology built upon heterogeneity in space and time. It frequently included anthropogenic (human-caused) landscape changes in theory and application of concepts.[15]

By 1980, landscape ecology was a discrete, established discipline. It was marked by the organization of the International Association for Landscape Ecology (IALE) in 1982. Landmark book publications defined the scope and goals of the discipline, including Naveh and Lieberman[16] and Forman and Godron[17]. Forman[6] wrote that although study of "the ecology of spatial configuration at the human scale" was barely a decade old, there was strong potential for theory development and application of the conceptual framework.Today, the theory and application of landscape ecology continue to develop through a need for innovative applications in a changing landscape and environment. Landscape ecology relies on advanced technologies such as remote sensing, GIS, and models. There has been associated development of powerful quantitative methods to examine the interactions of patterns and processes.[5] An example would be determining the amount of carbon present in the soil based on landform over a landscape, derived from GIS maps, vegetation types, and rainfall data for a region. Remote sensing work has been used to extend landscape ecology to the field of predictive vegetation mapping, for instance by Janet Franklin.

Sources

- Wu, J. (2006). Landscape ecology, cross-disciplinarity, and sustainability science. Landscape Ecology, 21(1), pp. 1-4. doi:10.1007/s10980-006-7195-2. S2CID 27192835.

- Wu, J., & Hobbs, R., eds. (2007). Key topics in landscape ecology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Wu, J. (2008). Landscape ecology. In Jorgensen, S.E. (Eds.), Encyclopedia of ecology. Oxford: Elsevier.

- Leser, H., & Nagel, P. (2001). Landscape diversity -- a holistic approach. Biodiversity. Springer, pp. 129-143. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-06071-1_9. ISBN 978-3-642-08370-9.

- Turner, M.G., Gardner, R.H., & O'Neill, R.V. (2001). Landscape ecology in theory and practice. New York, NY, USA: Springer-Verlag.

- Forman, R.T. (1995). Land mosaics: The ecology of landscapes and regions. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Wu & Hobbs 2002

- Bloomfield, L.S., McIntosh, T.L., & Lambin, E.F. (2020). Habitat fragmentation, livelihood behaviors, and contact between people and nonhuman primates in Africa. Landscape Ecology, 35(4), pp. 985-1000. doi:10.1007/s10980-020-00995-w. ISSN 1572-9761. S2CID 214731443.

- Bausch, D.G., & Scwarz, L. (2014). Outbreak of ebola virus disease in Guinea: Where ecology meets economy. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 8(7), e3056. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0003056. PMC 4117598. PMID 25079231.

- Troll, C. (1939). Luftbildplan und ökologische Bodenforschung [Aerial photography and ecological studies of the earth]. Zeitschrift der Gesellschaft für Erdkunde (in German). Berlin: pp. 241–298.

- Turner, M.G. (1989). Landscape ecology: The effect of pattern on process. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 20, pp. 171-197. doi:10.1146/annurev.es.20.110189.001131.

- Allaby, M. (1998). Oxford dictionary of ecology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Banaszak, J., ed. (2000). Ecology of forest islands. Bydgoszcz, Poland: Bydgoszcz University Press. p. 313.

- Steiniger, S., & Hay, G.J. (2009). Free and open source geographic information tools for landscape ecology. Ecological Informatics, 4(4), pp, 183-95. doi:10.1016/j.ecoinf.2009.07.004.

- Sanderson, J., Harris, L.D., eds. (2000). Landscape ecology: A top-down approach. Boca Raton, Florida, USA: Lewis Publishers.

- Naveh, Z., & Lieberman, A. (1984). Landscape ecology: Theory and application. New York, NY, USA: Springer-Verlag.

- Forman, R.T., & Godron, M. (1986). Landscape ecology. New York, NY, USA: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

- Ryszkowski, L., ed. (2002). Landscape ecology in agroecosystems management. Florida, USA: CRC Press, Boca Raton.

Contributors and Attributions

Modified by Andy Wilson (Gettysburg College) and Kyle Whittinghill (University of Vermont) from the following sources:

- Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia https://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Landscape_ecology