3.3: Chemical Bonding

- Page ID

- 16727

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)When you think of bonding, you may not think of ions. Like most of us, you probably think of bonding between people. Like people, molecules bond — and some bonds are stronger than others. It's hard to break up a mother and baby, or a molecule made up of one oxygen and two hydrogen atoms! A chemical bond is a force of attraction between atoms or ions. Bonds form when atoms share or transfer valence electrons. Valence electrons are the electrons in the outer energy level of an atom that may be involved in chemical interactions. Valence electrons are the basis of all chemical bonds.

Why Bonds Form

To understand why chemical bonds form, consider the common compound known as water, or H2O. It consists of two hydrogen (H) atoms and one oxygen (O) atom. As you can see in the on the left side of the Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) below, each hydrogen atom has just one electron, which is also its sole valence electron. The oxygen atom has six valence electrons. These are the electrons in the outer energy level of the oxygen atom.

In the water molecule on the right in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\), each hydrogen atom shares a pair of electrons with the oxygen atom. By sharing electrons, each atom has electrons available to fill its sole or outer energy level. The hydrogen atoms each have a pair of shared electrons, so their first and only energy level is full. The oxygen atom has a total of eight valence electrons, so its outer energy level is full. A full outer energy level is the most stable possible arrangement of electrons. It explains why elements form chemical bonds with each other.

Types of Chemical Bonds

Not all chemical bonds form in the same way as the bonds in water. There are actually four different types of chemical bonds that we will discuss here are non-polar covalent, polar covalent, hydrogen, and ionic bonding. Each type of bond is described below.

Non-polar Covalent Bonds

For methane (CH4) in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\), the carbon atom (with four electrons in its outermost valence energy shell) shares a single electron from each of the four hydrogens. Hydrogen has one valence electron in its first energy shell. Covalent bonding is prevalent in organic compounds. In fact, your body is held together by electrons shared by carbons and hydrogens! The electrons are equally shared in all directions; therefore, this type of covalent bond is referred to as non-polar.

Polar Covalent Bonds and Hydrogen Bonds

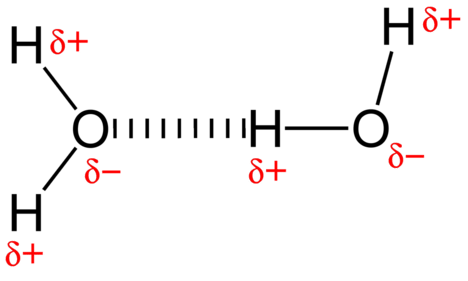

A covalent bond is the force of attraction that holds together two nonmetal atoms that share a pair of electrons. One electron is provided by each atom, and the pair of electrons is attracted to the positive nuclei of both atoms. The water molecule represented in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) contains polar covalent bonds.

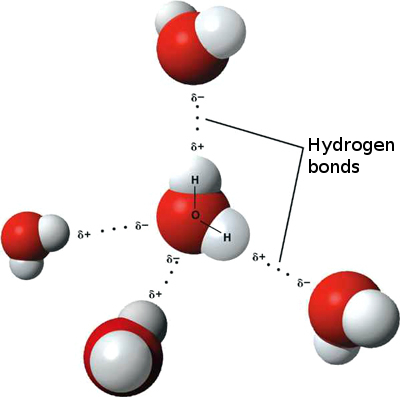

The attractive force between water molecules is a dipole interaction. The hydrogen atoms are bound to the highly electronegative oxygen atom (which also possesses two lone pair sets of electrons, making for a very polar bond. The partially positive hydrogen atom of one molecule is then attracted to the partially negative oxygen atom of a nearby water molecule as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) ).

A hydrogen bond is an intermolecular and intramolecular attractive force in which a hydrogen atom that is covalently bonded to a highly electronegative atom is attracted to a lone pair of electrons on an atom or a partially negative atom in a neighboring polar molecule. Hydrogen bonds are also found intramolecularly in the tertiary and quaternary structures of protein and DNA strands.

Hydrogen bonding occurs only in molecules where hydrogen is covalently bonded to one of three elements: fluorine, oxygen, or nitrogen. These three elements are so electronegative that they withdraw the majority of the electron density in the covalent bond with hydrogen, leaving the H atom very electron-deficient. The H atom nearly acts as a bare proton, leaving it very attracted to lone pair electrons on a nearby atom.

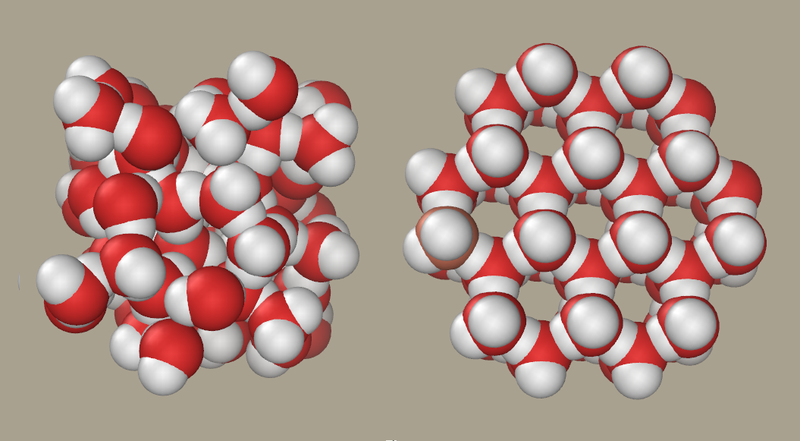

The hydrogen bonding that occurs in water leads to some unusual, but very important properties. Most molecular compounds that have a mass similar to water are gases at room temperature. Because of the strong hydrogen bonds, water molecules are able to stay condensed in the liquid state. Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\) shows how the bent shape and two hydrogen atoms per molecule allow each water molecule to be able to hydrogen bond to two other molecules.

In the liquid state, the hydrogen bonds of water can break and reform as the molecules flow from one place to another. When water is cooled, the molecules begin to slow down. Eventually, when water is frozen to ice, the hydrogen bonds form a very specific network shown on the right side of Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\). When water is liquid, the molecules are more motile and don't produce this rigid structure.

Ionic bonds

Electrons are transferred between atoms. An ion will give one or more electrons to another ion. Table salt, sodium chloride (NaCl), is a common example of an ionic compound. Note that sodium is on the left side of the periodic table and that chlorine is on the right side of the periodic table. In Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\), an atom of lithium donates an electron to an atom of fluorine to form an ionic compound. This happens to full fill their outermost valence shell. The transfer of the electron gives the lithium ion a net charge of +1, and the fluorine ion a net charge of -1. These ions bond because they experience an attractive force due to the difference in sign of their charges.

Review

- How is a covalent bond different from an ionic bond?

- Why is a hydrogen bond a relatively weak bond?

- Diagram the polarity of a water molecule.

- What is a chemical bond?

- Explain why hydrogen and oxygen atoms are more stable when they form bonds in a water molecule.

- How many valence electrons does sodium have? How many valence electrons does chlorine have? How does a chlorine atom bonds with sodium? What is the charge on a sodium ion? What about the chlorine ion?

- When does covalent bonding occur? How does it work?

- How many valence electrons does oxygen have?

Explore More

Attributions

- Mother & daughter by Lyd235, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

- Water molecule by CNX OpenStax, licensed CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

- Covalent bond by DynaBlast, licensed CC BY-SA 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons

- Hydrogen bonding in water, public domain via Wikimedia Commons

- 3D model hydrogen bonds by Michal Maňas, public domain via Wikimedia Commons

- Liquid water and ice by P99am, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

- NaF by Wdcf, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

- Text adapted from Human Biology by CK-12 licensed CC BY-NC 3.0