5.7: Foodborne Diseases

- Page ID

- 92593

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Picnics like this one can be a lot of fun. Food always seems to taste better when eaten outdoors. Ants and other insects can be attracted to picnic foods and be annoying. However, a greater potential hazard may lurk within the picnic foods themselves: microorganisms that cause foodborne disease.

What Is Foodborne Disease?

Foodborne disease, commonly called food poisoning, is any disease that is transmitted via food. Picnic foods create a heightened risk of foodborne disease mainly because of problems with temperature control. If hot foods are not kept hot enough or cold foods are not kept cold enough, foods may enter a temperature range in which microorganisms such as bacteria can thrive.

Many people do not think about food safety until a foodborne disease affects them or a family member. While the food supply in the United States is one of the safest in the world, the CDC estimates that 76 million Americans a year get a foodborne disease, of whom more than 300,000 are hospitalized and 5,000 die. Preventing foodborne disease remains a major public health challenge.

Causes of Foodborne Disease

Most foodborne diseases are caused by microorganisms in food. Some are caused by toxins in food or adulteration of food by foreign bodies.

Microorganisms

Microorganisms that cause foodborne diseases include bacteria, viruses, parasites, and prions. The four most common foodborne pathogens in the United States are a virus called norovirus and three genera of bacteria: Salmonella species (such as Salmonella typhimurium, pictured below), Clostridium perfringens, and Campylobacter jejune. Although norovirus causes many more cases of foodborne disease, Salmonella species are the pathogens in food that are most likely to be deadly. Parasites that cause human foodborne diseases are mostly zoonoses — animal infections that can be transmitted to humans. Parasites such as pork tapeworm (Taenia solium) are ingested when people eat inadequately cooked infected animal tissue. The prions that cause mad-cow disease have been transmitted to people through the ingestion of contaminated beef.

Toxins

Toxins are another common cause of foodborne disease. Toxins may come from a variety of sources. Foods may be contaminated with toxins in the environment. Pesticides applied to farm fields are common examples of environmental food toxins. Toxins may be produced by microorganisms in food. An example is botulism toxin that is produced by the bacterium Clostridium botulinum. Some toxins occur naturally in certain plants and fungi. A common example is mushrooms. Dozens of species are poisonous and some are deadly, like the aptly named death-cap mushroom pictured below. Many deadly mushrooms look similar to edible species, making them even more dangerous. Food plants can also be infected with fungi that make people sick when they eat the plants. Fungi in the genus Aspergillus are frequently found in nuts, maize, and corn. They produce a toxin called aflatoxin, which targets the liver, potentially causing cirrhosis of the liver and liver cancer.

Adulteration by Foreign Bodies

Another potential cause of the foodborne disease is the adulteration of foods by foreign bodies. Foreign bodies refer to any substances or particles that are not meant to be foods. They can include pests such as insects, animal feces such as mouse droppings, hairs (human or nonhuman), cigarette butts, and wood chips, to name just a few. Some foods are at risk of contamination with lead or other toxic chemicals because they are stored or cooked in unsafe containers, such as ceramic pots with lead-based glaze.

Characteristics of Foodborne Diseases

Foodborne diseases differ in specific characteristics but they share some commonalities, often including similar symptoms.

Symptoms and Incubation Period

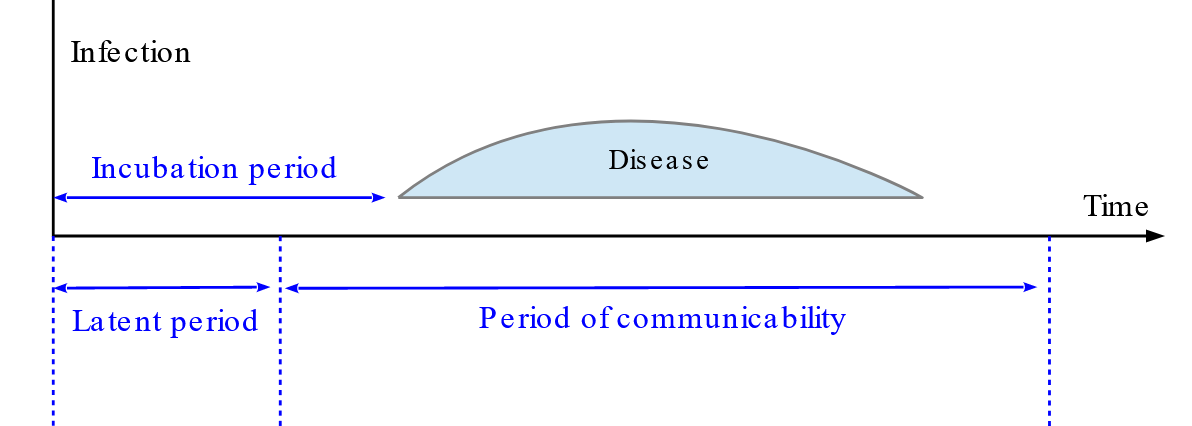

Foodborne diseases commonly cause gastrointestinal symptoms such as vomiting and diarrhea. They also frequently cause fevers, aches, and pains. The length of time between the consumption of contaminated food and the first appearance of symptoms is called the incubation period. This concept is illustrated in the figure below. The incubation period for a foodborne disease can range from a few hours to several days or even longer, depending on the cause of the disease. Toxins generally cause symptoms sooner than microorganisms. When symptoms do not appear for days, it is difficult to connect them with the agent that caused them.

During the incubation period, microbes generally pass through the stomach and into the small intestine. Once in the small intestine, they attach to cells lining the intestinal walls and begin to multiply. Some types of microbes stay in place in the intestine, although they may produce toxins that are absorbed into the bloodstream and carried to cells throughout the body. Other types of microbes directly invade deeper body tissues.

Infectious Dose

Whether a person becomes ill from a microbe or a toxin depends on how much of the agent was consumed. The amount that must be consumed to cause disease is called the infectious dose. It varies by disease agent and also by host factors, such as age and overall health.

Sporadic Cases vs. Outbreaks

The vast majority of reported cases of foodborne disease occur as sporadic cases in individuals. The origin of most sporadic cases is never determined. Only a small number of foodborne disease cases happen as part of disease outbreaks. An outbreak of a foodborne disease occurs when two or more people experience the same disease after consuming food from a common source. The majority of foodborne disease outbreaks originate in restaurants, but they also originate in nursing homes, hospitals, schools, and summer camps.

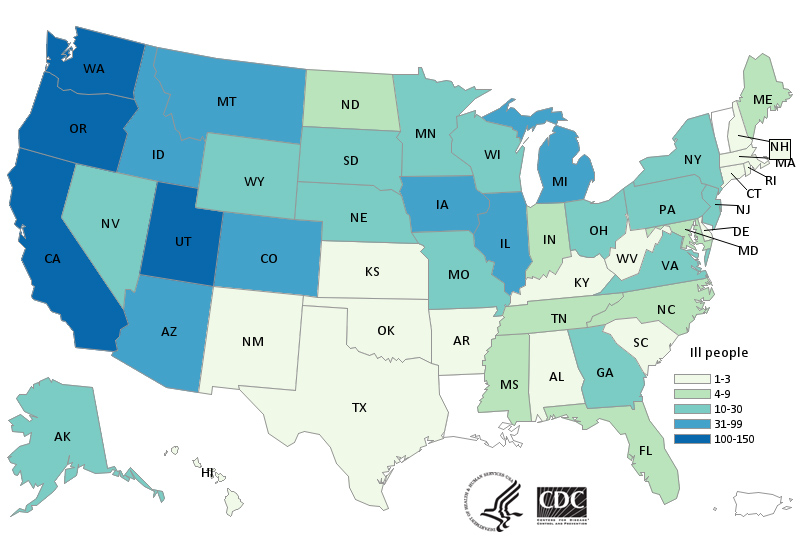

An example of a foodborne disease outbreak in the United States is the Salmonella outbreak shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\). The CDC map below shows where most of the cases occurred. The reported cases began in July and were traced back to onions produced in California. Within 2 weeks the onions were recalled. The outbreak was over by October. Overall, a total of 1,127 people across 48 states, were infected with the outbreak strain of Salmonella Newport. There were 167 hospitalizations and no deaths reported.

Factors that Increase the Risk of Food Contamination

The foodborne disease usually arises from food contamination through improper handling, preparation, or storage of food. Food can become contaminated at any stage from the farmer’s field to the consumer’s plate.

Poor Hygiene

Many foods become contaminated by microorganisms because of poor hygienic practices, such as handling or preparing foods with unwashed hands. Consider norovirus, the leading cause of foodborne disease in the United States. The virus can easily contaminate food because it is very tiny and highly infective. People sick with the virus shed billions of virus particles. Unfortunately, It takes fewer than 20 virus particles to make someone else sick. Food can become contaminated with virus particles when infected people get stool or vomit on their hands and then fail to wash their hands before handling food. People who consume food can ingest the virus particles and get sick.

Cross-Contamination

Another major way that foods become contaminated is through cross-contamination. This occurs when microbes are transferred from one food to another. Some raw foods commonly contain bacteria such as Salmonella, including eggs, poultry, and meat. These foods should never come into contact with ready-to-eat foods, such as raw fruits and vegetables or bread. If a cutting board, knife, or counter-top is used to prepare contaminated foods, it should not be used to prepare other foods without proper cleaning in between.

Failure of Temperature Control

Foods contaminated with bacteria or other microorganisms may become even more dangerous if failure of temperature control allows the rapid multiplication of microorganisms. Bacteria generally multiply most rapidly at temperatures between about 4 and 60 degrees C (40 and 140 degrees F). Perishable foods that remain within that temperature range for more than two hours may become dangerous to eat because of rapid bacterial growth.

Prevention of Foodborne Disease

Preventing foodborne disease is both a personal and a society-wide problem. Both governments and individuals must work to solve it.

The Government’s Role

In the United States, the prevention of foodborne disease is mainly the role of government agencies such as the Food and Drug Administration and local departments of health. Such government agencies are responsible for setting and enforcing strict rules of hygiene in food handling in stores and restaurants (see the sign below). Government agencies are also responsible for enforcing safety regulations in food production, from the way foods are grown and processed to the way they are shipped and stored. Government regulations require that food to be traceable to their point of origin and date of processing. This helps epidemiologists identify the source of foodborne disease outbreaks.

Food Safety at Home

At home, the prevention of foodborne disease depends mainly on good food safety practices.

- Regular handwashing is one of the most effective defenses against the spread of foodborne diseases. Always wash hands before and after handling or preparing food and before eating.

- Rotate food in your pantry so older items are used first. Make sure foods have not expired before you consume them. Be aware that perishable foods such as unpreserved meats and dairy products have a relatively short storage life, usually just a few days in the refrigerator.

- Rinse fresh produce before eating. This is especially important if the produce is to be eaten raw. Even if you do not plan to eat the outer skin or rind, wash it because microbes or toxins on the surface can contaminate the inside when the food is cut open or peeled.

- Many bacteria in food can be killed by thorough cooking, but food must reach an internal temperature of at least 74 degrees C (165 degrees F) to kill any bacteria the food contains. Use a cooking thermometer like the one pictured below to ensure food gets hot enough to make it safe to eat.

- Foods meant to be eaten hot should be kept hot until served, and foods meant to be eaten cold should be kept refrigerated until served. Perishable leftovers should be refrigerated as soon as possible. Any perishable foods left at a temperature between 4 and 60 degrees C (40 and 140 degrees F) for more than two hours should be thrown out.

- Make sure the temperature in the refrigerator is kept at or below 4 degrees C (40 degrees F) to inhibit bacterial growth in refrigerated foods. If your refrigerator does not have a built-in thermometer, you can buy one to monitor the temperature. This is especially important in a power outage. If the temperature stays below 40 degrees F until the power comes back on, the food is safe to eat. If the temperature goes above 40 degrees F for two hours or more, the food may no longer be safe and should not be consumed.

- Keep the temperature of the freezer below 18 degrees C (0 degrees F). Foods frozen at this temperature will keep indefinitely, although they may gradually deteriorate in quality.

- Do not thaw foods at room temperature. Freezing foods does not kill microbes; it preserves them. They will become active again as soon as they thaw. Either thaw frozen foods slowly in the refrigerator or thaw them quickly in the microwave, cool water, or while cooking. Never refreeze food once it has thawed.

Myths about foodborne diseases abound. Some of the most common myths are debunked below.

Myth: It must have been the mayonnaise.

Reality: Mayonnaise is acidic enough that it does not provide a good medium for the growth of bacteria unless it becomes heavily contaminated by a dirty utensil or is mixed with other foods that decrease its acidity. Mayo may have gotten a bad rap because it is often consumed at picnics, where temperature control may be poor and lead to bacterial growth in other, non-acidic foods.

Myth: Foodborne disease is caused by food that has “gone bad.”

Reality: Eating spoiled or rotten food is seldom the cause of foodborne disease. Most cases of foodborne disease are caused by contamination of food by unwashed hands or cross-contamination of food by unwashed utensils or cutting boards.

Myth: Foodborne disease is caused by eating restaurant foods.

Reality: Foodborne disease is caused by contamination of foods in the home as well as in restaurants. Restaurant kitchens must be regularly inspected to ensure sanitary conditions for food preparation. There are no such inspections of home kitchens.

Myth: Foodborne disease is caused by the last food eaten.

Reality: Symptoms of the foodborne disease may not strike for several hours to several days following infection, so the last meal eaten may not be the culprit. This makes it very difficult to know which food caused the symptoms.

Review

- What is a foodborne disease?

- How common are foodborne diseases in the United States?

- What are the main causes of foodborne disease? Give examples of each cause.

- Define the incubation period and infectious dose.

- Discuss similarities and differences among foodborne diseases.

- Compare and contrast sporadic cases and disease outbreaks of foodborne disease.

- What are the three main ways that food becomes contaminated?

- List three food safety practices that can help prevent transmission of foodborne disease in the home.

- If you store cooked leftovers at room temperature (about 68 degrees F) for more than two hours, are they safe to eat if you heat them up well first? Explain your answer.

- True or False. There is no need to wash a melon before cutting it because you will not be eating the rind.

- True or False. Foodborne diseases can sometimes cause a form of cancer.

- Explain why it can be hard to trace the source of a foodborne disease if it has a long incubation period.

- Which are a bacterial species that can cause foodborne disease?

- Clostridium perfringens

- Norovirus

- Taenia solium

- All of the above

- Why do you think the incubation period for a foodborne disease is generally shorter when the agent is a toxin compared to a microorganism?

- Why do you think it is often recommended to rapidly cool a large quantity of homemade soup by putting the pot in an ice water bath before storing it in the refrigerator?

Attributions

- Picnic by Dylan Lake, licensed CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

- Salmonella by US gov, public domain via Wikimedia Commons

- Amanita phalloides by George Chernilevsky, public domain via Wikimedia Commons

- Concept of incubation period by Patilsaurabhr, public domain via Wikimedia Commons

- Salmonella outbreak by CDC, public domain

- Clean hands guardians of health by CDC/ Minnesota Department of Health, R.N. Barr Library; Librarians Melissa Rethlefsen and Marie Jones, public domain via Wikimedia Commons

- Pork thermometer by USDA, public domain via Wikimedia Commons

- Text adapted from Human Biology by CK-12 licensed CC BY-NC 3.0