8.3: Environmental Toxicology

- Page ID

- 81350

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Environmental toxicology is the scientific study of the health effects associated with exposure to toxic chemicals (Table 1) occurring in the natural, work, and living environments. The term also describes the management of environmental toxins and toxicity and the development of protections for humans and the environment.

Click here for how to do an environmental risk assessment from the EPA: https://www.epa.gov/risk/human-health-risk-assessment

Introduction

Just because something is a chemical, does not make it bad. After all, water is a chemical, air is a chemical, you are made of chemicals. The same goes for something that is labeled “natural” (which, by the way, has no legal definition). Arsenic is natural, cyanide is natural, and radiation is natural. None of those are good for you.

In this section, we will specifically be looking at hazards in the environment. Some of these are natural, some contain natural ingredients, and some are produced entirely by humans. The toxicological hazards described below are those humans can be exposed to and are often used by humans to change something about our environment.

What Makes Something Hazardous?

A hazardous substance is defined in federal government regulations as “one that may cause substantial personal injury or illness during reasonable handling or use, including possible ingestion by children.”

According to the Federal Hazardous Substances Act (FHSA), household products are hazardous if they contain substances that have one or more of the following hazardous properties:

- Corrosive: A product that can burn or destroy living tissue, such as skin or eyes or by chemical action.

- Examples: Drain cleaners, oven cleaners, and lye.

- Irritant: A product is an irritant if it is not corrosive and causes injury to the area of the body that it comes in contact with after immediate, prolonged, or repeated contact.

- Examples: Toilet cleaners, chlorine bleach cleaners, and some pool chemicals.

- Strong Sensitizer: A product that can cause an allergic reaction upon repeated uses of the same substance. Usually this does not happen when a person first comes in contact with the product, but after a second exposure.

- Examples: Dyes, oils, tars, rubber, soaps, cosmetics, perfume, insecticides, wood resins, plants, paints, plastics, glues, fiberglass, metals, and polishes.

- Flammable: Any substance, liquid, solid, or the contents of a self-pressurized container, like aerosol cans, that can be easily set on fire or ignited. Extremely flammable, flammable, and combustible are the three types of flammability based on testing.

- Examples: Paint thinners, some solvents, adhesives, rubber cement, and hair spray.

- Toxic: A product is toxic if it can cause long-term effects like cancer, birth defects, or neurotoxicity (toxic to nerves).

- Examples: Brake fluids, fungicides, insecticides, fertilizers, rat poison, and antifreeze.

Routes of Exposure to Chemicals

Any product is hazardous if it can cause personal injury or illness to humans. To cause health problems, chemicals must be able to enter your body.

There are three main “routes of exposure,” or ways a hazard can get into your body.

- Ingestion: Eating or drinking hazardous substances or contaminated foods and water and absorbing these substances through your gastrointestinal tract.

- Inhalation: Breathing in gases, vapors, and sprays that are absorbed through the lungs and enter the bloodstream.

- Dermal (skin or eye contact): Some hazardous products can be absorbed through the skin or your eyes and cause injuries.

Once chemicals have entered your body, some can move into your bloodstream and reach internal “target” organs, such as the lungs, liver, kidneys, or nervous system.

What Forms do Chemicals Take?

Chemical substances can take a variety of forms. They can be in the form of solids, liquids, dusts, vapors, gases, fibers, mists and fumes. The form a substance is in has a lot to do with how it gets into your body and what harm it can cause. A chemical can also change forms. For example, liquid solvents can evaporate and give off vapors that you can inhale. Sometimes chemicals are in a form that can’t be seen or smelled, so they can’t be easily detected.

What Health Effects Can Chemicals Cause?

An acute effect of a contaminant (The term “contaminant” means hazardous substances, pollutants, pollution, and chemicals) is one that occurs rapidly after exposure to a large amount of that substance. A chronic effect of a contaminant results from exposure to small amounts of a substance over a long period of time. In such a case, the effect may not be immediately obvious. Chronic effect are difficult to measure, as the effects may not be seen for years. Long-term exposure to cigarette smoking, low level radiation exposure, and moderate alcohol use are all thought to produce chronic effects.

For centuries, scientists have known that just about any substance is toxic in sufficient quantities. For example, small amounts of selenium are required by living organisms for proper functioning, but large amounts may cause cancer. The effect of a certain chemical on an individual depends on the dose (amount) of the chemical. This relationship is often illustrated by a dose-response curve which shows the relationship between dose and the response of the individual. Lethal doses in humans have been determined for many substances from information gathered from records of homicides, accidental poisonings, and testing on animals.

A dose that is lethal to 50% of a population of test animals is called the lethal dose-50% or LD-50. Determination of the LD-50 is required for new synthetic chemicals in order to give a measure of their toxicity. A dose that causes 50% of a population to exhibit any significant response (e.g., hair loss, stunted development) is referred to as the effective dose-50% or ED-50. Some toxins have a threshold amount below which there is no apparent effect on the exposed population.

Environmental Contaminants

The contamination of the air, water, or soil with potentially harmful substances can affect any person or community. Contaminants (Table 2) are often chemicals found in the environment in amounts higher than what would be there naturally. We can be exposed to these contaminants from a variety of residential, commercial, and industrial sources. Sometimes harmful environmental contaminants occur biologically, such as mold or a toxic algae bloom.

| Contaminant | Definition |

|---|---|

| Carcinogen | An agent which may produce cancer (uncontrolled cell growth), either by itself or in conjunction with another substance. Examples include formaldehyde, asbestos, radon, vinyl chloride, and tobacco. |

| Teratogen |

A substance which can cause physical defects in a developing embryo. Examples include alcohol and cigarette smoke. |

| Mutagen | A material that induces genetic changes (mutations) in the DNA. Examples include radioactive substances, x-rays and ultraviolet radiation. |

| Neurotoxicant |

A substance that can cause an adverse effect on the chemistry, structure or function of the nervous system. Examples include lead and mercury. |

|

Endocrine disruptor |

A chemical that may interfere with the body’s endocrine (hormonal) system and produce adverse developmental, reproductive, neurological, and immune effects in both humans and wildlife. A wide range of substances, both natural and man-made, are thought to cause endocrine disruption, including pharmaceuticals, dioxin and dioxin-like compounds, arsenic, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), DDT and other pesticides, and plasticizers such as bisphenol A (BPA). |

An Overview of Some Common Contaminants

Arsenic is a naturally occurring element that is normally present throughout our environment in water, soil, dust, air, and food. Levels of arsenic can regionally vary due to farming and industrial activity as well as natural geological processes. The arsenic from farming and smelting tends to bind strongly to soil and is expected to remain near the surface of the land for hundreds of years as a long-term source of exposure. Wood that has been treated with chromated copper arsenate (CCA) is commonly found in decks and railing in existing homes and outdoor structures such as playground equipment. Some underground aquifers are located in rock or soil that has naturally high arsenic content.

Most arsenic gets into the body through ingestion of food or water. Arsenic in drinking water is a problem in many countries around the world, including Bangladesh, Chile, China, Vietnam, Taiwan, India, and the United States. Arsenic may also be found in foods, including rice and some fish, where it is present due to uptake from soil and water. It can also enter the body by breathing dust containing arsenic. Researchers are finding that arsenic, even at low levels, can interfere with the body’s endocrine system. Arsenic is also a known human carcinogen associated with skin, lung, bladder, kidney, and liver cancer.

Mercury is a naturally occurring metal, a useful chemical in some products, and a potential health risk. Mercury exists in several forms; the types people are usually exposed to are methylmercury and elemental mercury. Elemental mercury at room temperature is a shiny, silver-white liquid which can produce a harmful odorless vapor. Methylmercury, an organic compound, can build up in the bodies of long-living, predatory fish. To keep mercury out of the fish we eat and the air we breathe, it’s important to take mercury-containing products to a hazardous waste facility for disposal. Common products sold today that contain small amounts of mercury include fluorescent lights and button-cell batteries.

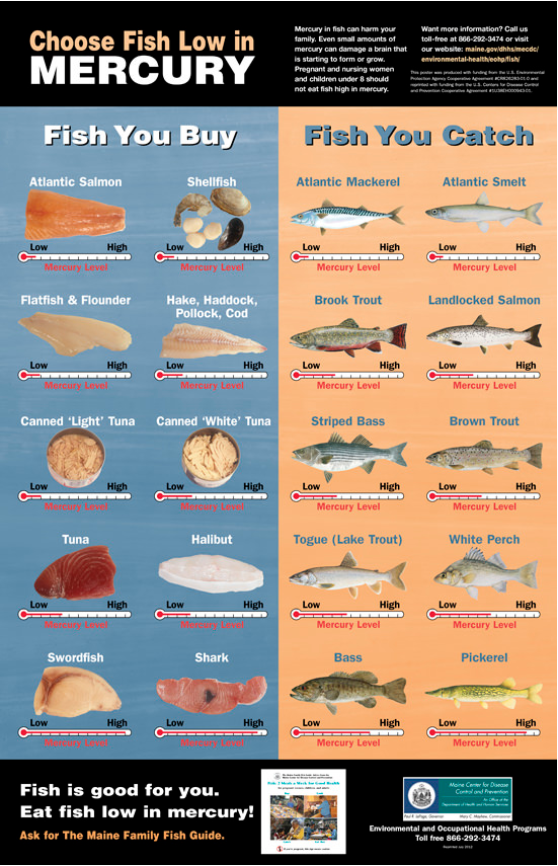

Although fish and shellfish have many nutritional benefits, consuming large quantities of fish increases a person’s exposure to mercury. Pregnant women who eat fish high in mercury on a regular basis run the risk of permanently damaging their developing fetuses. Children born to these mothers may exhibit motor difficulties, sensory problems and cognitive deficits. Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) identifies the typical (average) amounts of mercury in commonly consumed commercial and sport-caught fish.

Bisphenol A (BPA) is a chemical synthesized in large quantities for use primarily in the production of polycarbonate plastics and epoxy resins. Polycarbonate plastics have many applications including use in some food and drink packaging, e.g., water and infant bottles, compact discs, impact-resistant safety equipment, and medical devices. Epoxy resins are used as lacquers to coat metal products such as food cans, bottle tops, and water supply pipes. Some dental sealants and composites may also contribute to BPA exposure. The primary source of exposure to BPA for most people is through the diet. Bisphenol A can leach into food from the protective internal epoxy resin coatings of canned foods and from consumer products such as polycarbonate tableware, food storage containers, water bottles, and baby bottles. The degree to which BPA leaches from polycarbonate bottles into liquid may depend more on the temperature of the liquid or bottle, than the age of the container. BPA can also be found in breast milk.

What can I do to prevent exposure to BPA?

Some animal studies suggest that infants and children may be the most vulnerable to the effects of BPA. Parents and caregivers, can make the personal choice to reduce exposures of their infants and children to BPA:

- Don’t microwave polycarbonate plastic food containers. Polycarbonate is strong and durable, but over time it may break down from over use at high temperatures.

- Plastic containers have recycle codes on the bottom. Some, but not all, plastics that are marked with recycle codes 3 or 7 may be made with BPA.

- Reduce your use of canned foods.

- When possible, opt for glass, porcelain or stainless steel containers, particularly for hot food or liquids.

- Use baby bottles that are BPA free.

Phthalates are a group of synthetic chemicals used to soften and increase the flexibility of plastic and vinyl. Polyvinyl chloride is made softer and more flexible by the addition of phthalates. Phthalates are used in hundreds of consumer products. Phthalates are used in cosmetics and personal care products, including perfume, hair spray, soap, shampoo, nail polish, and skin moisturizers. They are used in consumer products such as flexible plastic and vinyl toys, shower curtains, wallpaper, vinyl miniblinds, food packaging, and plastic wrap. Exposure to low levels of phthalates may come from eating food packaged in plastic that contains phthalates or breathing dust in rooms with vinyl miniblinds, wallpaper, or recently installed flooring that contain phthalates. We can be exposed to phthalates by drinking water that contains phthalates. Phthalates are suspected to be endocrine disruptors.

Lead is a metal that occurs naturally in the rocks and soil of the earth’s crust. It is also produced from burning fossil fuels such as coal, oil, gasoline, and natural gas; mining; and manufacturing. Lead has no distinctive taste or smell. The chemical symbol for elemental lead is Pb. Lead is used to produce batteries, pipes, roofing, scientific electronic equipment, military tracking systems, medical devices, and products to shield X-rays and nuclear radiation. It is used in ceramic glazes and crystal glassware. Because of health concerns, lead and lead compounds were banned from house paint in 1978; from solder used on water pipes in 1986; from gasoline in 1995; from solder used on food cans in 1996; and from tin-coated foil on wine bottles in 1996. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has set a limit on the amount of lead that can be used in ceramics.

Lead and lead compounds are listed as “reasonably anticipated to be a human carcinogen”. It can affect almost every organ and system in your body. It can be equally harmful if breathed or swallowed. The part of the body most sensitive to lead exposure is the central nervous system, especially in children, who are more vulnerable to lead poisoning than adults. A child who swallows large amounts of lead can develop brain damage that can cause convulsions and death; the child can also develop blood anemia, kidney damage, colic, and muscle weakness. Repeated low levels of exposure to lead can alter a child’s normal mental and physical growth and result in learning or behavioral problems. Exposure to high levels of lead for pregnant women can cause miscarriage, premature births, and smaller babies. Repeated or chronic exposure can cause lead to accumulate in your body, leading to lead poisoning.

Formaldehyde is a colorless, flammable gas or liquid that has a pungent, suffocating odor. It is a volatile organic compound, which is an organic compound that easily becomes a vapor or gas. It is also naturally produced in small, harmless amounts in the human body. The primary way we can be exposed to formaldehyde is by breathing air containing it. Releases of formaldehyde into the air occur from industries using or manufacturing formaldehyde, wood products (such as particle-board, plywood, and furniture), automobile exhaust, cigarette smoke, paints and varnishes, and carpets and permanent press fabrics. Nail polish, and commercially applied floor finish emit formaldehyde.

In general, indoor environments consistently have higher concentrations than outdoor environments, because many building materials, consumer products, and fabrics emit formaldehyde. Levels of formaldehyde measured in indoor air range from 0.02–4 parts per million (ppm). Formaldehyde levels in outdoor air range from 0.001 to 0.02 ppm in urban areas.

How Do You Know if a Household Product is Hazardous?

The FSHA requires that if a product contains a hazardous substance, the product must bear a label of specific size, and the label must contain certain information, depending on the toxicity of the product.

“Signal Words” are found on every hazardous product label and indicate how toxic or hazardous a product could be (Table 2). If a signal word is not on a product, it is not hazardous.

Table 2. FSHA Signal Words for Household Products

|

Signal Words |

Properties |

Examples |

|

POISON |

highly toxic |

varnish remover, antifreeze |

|

DANGER |

extremely flammable, corrosive, or highly toxic |

bleach, WD-40 |

|

WARNING CAUTION |

all other hazardous products |

carpet cleaner, cleanser |

Pesticides Have Additional Labeling

Pesticides are defined as chemicals used to prevent, destroy, or repel pests: insects, mice, weeds, fungi, and bacteria. Pesticides also include household products, such as disinfectants or cleaners that are used to destroy the growth of harmful bacteria, viruses, or fungi on household surfaces.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) registers and regulates pesticides under the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA). These products must meet the basic standards:

- the product will not cause harmful effects to human health or the environment, and

- product labeling must meet FIFRA requirements. Examples: insecticides, rodenticides, herbicides, fungicides, microbial pesticides, etc.

Pesticides also have signal words, but they are based on the degree of toxicity or how poisonous the product is (Table 3). Tests are conducted to determine the Lethal Dose50 (LD50) of each pesticide.

LD50 is when 50% of the test population, which is usually mice or rats, dies when administered a specific dose of a pesticide. This is then calculated to a human dose.

The oral LD50 of a substance is expressed in milligrams of chemical per kilogram of body weight (mg/kg).

Table 3. FIFRA Signal Words and Toxicity Rating Scale for Pesticides

|

Signal Words |

Toxicity |

Oral LD50 (mg/kg) |

Examples |

|

DANGER-POISON |

highly toxic |

0 - 50 |

indoor/outdoor insect killer |

|

DANGER |

highly toxic/corrosive |

0 - 50 |

toilet bowl cleaner |

|

WARNING |

moderately toxic |

50 - 500 |

flea spray |

|

CAUTION |

slightly toxic |

500 - 5,000 |

rat poison |

Read Before You Use!

Besides signal words, product labels contain other important information, such as instructions for safe handling, use, and storage, active ingredients, and first aid safety.

As a consumer, make it a habit to read all label information before using any product.

Radiation

Radiation is energy given off by atoms and is all around us. We are exposed to radiation every day from natural sources like soil, rocks, and the sun. We are also exposed to radiation from man-made sources like medical X-rays and smoke detectors. We’re even exposed to low levels of radiation on cross-country flights, from watching television, and even from some construction materials. You cannot see, smell or taste radiation. Some types of radioactive materials are more dangerous than others. So it’s important to carefully manage radiation and radioactive substances to protect health and the environment.

Radon is a radioactive gas that is naturally-occurring, colorless, and odorless. It comes from the natural decay of uranium or thorium found in nearly all soils. It typically moves up through the ground and into the home through cracks in floors, walls and foundations. It can also be released from building materials or from well water. Radon breaks down quickly, giving off radioactive particles. Long-term exposure to these particles can lead to lung cancer. Radon is the leading cause of lung cancer among nonsmokers, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and the second leading cause behind smoking.

Contributors and Attributions

- Essentials of Environmental Science by Kamala Doršner is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modified from the original by Tara Jo Holmberg and Matthew R. Fisher.