20.8: Colon (Large Intestine), Rectum, and Anus

- Page ID

- 53823

Colon (Large Intestine), Rectum, and Anus

This ileocecal valve controls the flow of chyme from the ileum into the cecum. Once chyme enters the large intestine, the “food” substance is then called feces.

The colon, also called the large intestine, processes feces after the majority of the nutrients have been absorbed in the small intestine. This organ is responsible for absorbing the water and electrolytes remaining in the feces in addition to absorbing vitamins, including B vitamins and vitamin K that are produced by colonic bacteria living in the colon. In fact, there are trillions of bacteria living in the colon that produce vitamins absorbed in the colon. These bacteria also have important immune roles, protecting the colon from infection. The colon also helps to store and propel waste from the body.

Above: Structures of the colon. (Left) Diagram of the different regions and structures of the colon. (Top right) some of the epiploic appendages are shown on the surface of the colon. (Bottom right) The colon is attached to the posterior body wall with serosa called mesocolon. The mesocolon is named for regions of colon it is attached to: ascending mesocolon, transverse mesocolon, descending mesocolon, and sigmoid mesocolon.

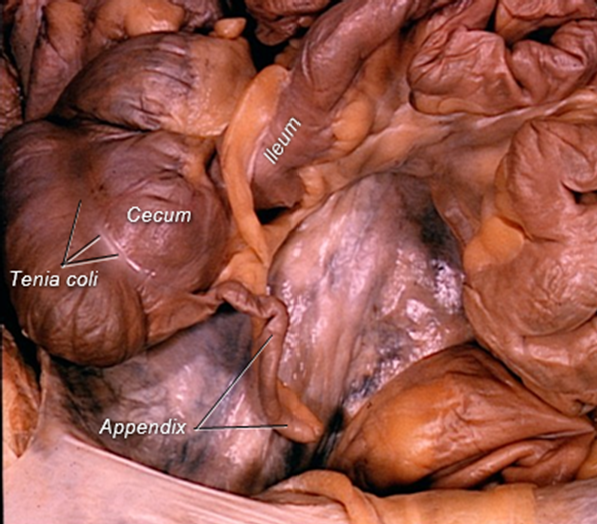

There are five regions of the colon. In order from the ileocecal valve to the rectum: cecum, ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon, and sigmoid colon. The cecum is a pouch where feces enter the colon and the appendix is attached and in the inferior aspect of the cecum. The terms ascending, transverse, and descending refer to the movements feces take as they move toward the rectum.

Above: Cadaver image of the cecum and appendix.

The colon has rounded pouches called haustra, each divided by indentations called haustral folds. Along the exterior surface of the colon are fatty appendages formed of peritoneum called epiploic appendages.

There are three flexures (a fancy way to say a bend or curve) in of the colon: right colic flexure (also called the hepatic flexure for its proximity to the liver), left colic flexure (also called the splenic flexure for its proximity to the spleen), and the sigmoid flexure (sigmoid = "S" or "C" shaped structure).

The tenia coli is a longitudinal band of muscle that spans the entire length of the large intestine. It helps move feces through the large intestine. There are a total of three tenia coli.

Above: The large intestine, composed of the four basic tunics, is differentiated from small intestine by the lack of villi, straight intestinal glands and taeniae coli. The large intestine was cut longitudinally through a taenia coli in the bottom left image. Tissue is magnified by 10x.

Above: The mucosa of the large intestine is lined by absorptive and goblet cells forming a simple columnar epithelium with microvilli. Goblet cells increase in number from the beginning to the termination of the large intestine, providing lubrication. A reduced number of enteroendocrine cells is present. Straight intestinal glands are typical of the large intestine. Tissue is magnified by 400x.

The descending colon, sigmoid colon, and rectum store feces until expelled. The sigmoid colon additionally aids in forcing feces from the body. For feces to pass from the body through the anus, it needs to pass through two sphincters: the internal anal sphincter and the external anal sphincter. The autonomic nervous system (involuntarily) controls your internal anal sphincter (smooth muscle), and there is voluntary control over the external anal sphincter (skeletal muscle).

Above: Diagram showing the position of the internal anal sphincter (smooth muscle, involuntary) and external anal sphincter (skeletal muscle, voluntary).

Clinical Application: Appendicitis

The appendix is a tube of tissue about the size of a pinky finger (exact thickness and length varies) attached to the cecum. The lumen of the appendix is continuous with that of the cecum, which allows fecal matter to fill the appendix. When the appendix is agitated (typically caused by a component of fecal matter getting stuck in the lumen), it becomes inflamed and is known as appendicitis. Symptoms of appendicitis include severe pain in the lower right quadrant of the abdomen (where the appendix is located), vomiting, and fever. Blood, urine, and radiographic tests can help verify the diagnosis. If left untreated, the inflamed appendix may perforate or rupture, allowing fecal matter and bacteria to spill into the abdominal cavity. This can cause peritonitis (inflammation of the peritoneum), which can be fatal. Therefore, medical attention should be sought immediately if appendicitis is suspected. Typical treatment includes consists of an emergency surgical procedure called an appendectomy to remove the appendix. Because they are sharp and do not digest, one of the most common things that become lodged in the appendix and cause appendicitis is fingernails!

Attributions

- "Anatomy 204L: Laboratory Manual (Second Edition)" by Ethan Snow, University of North Dakota is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

- "Digital Histology" by Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology and the Office of Faculty Affairs, Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine and the ALT Lab at Virginia Commonwealth University is licensed under CC BY 4.0

- "Gray's Anatomy plates" by Henry Vandyke Carte is in the Public Domain

- "Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014" by Blausen.com staff is licensed under CC BY 3.0