15.4: Ecology of Ecosystems

- Page ID

- 79091

Life in an ecosystem is often about competition for limited resources, a characteristic of the theory of natural selection. Competition in communities (all living things within specific habitats) is observed both within species and among different species. The resources for which organisms compete include organic material from living or previously living organisms, sunlight, and mineral nutrients, which provide the energy for living processes and the matter to make up organisms’ physical structures. Other critical factors influencing community dynamics are the components of its physical and geographic environment: a habitat’s latitude, amount of rainfall, topography (elevation), and available species. These are all important environmental variables that determine which organisms can exist within a particular area.

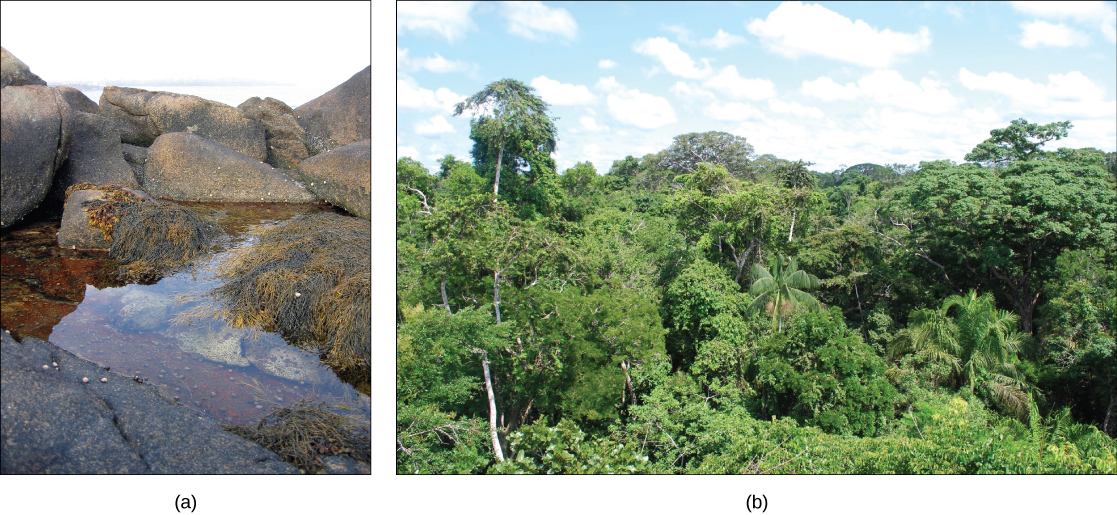

An ecosystem is a community of living organisms and their interactions with their abiotic (non-living) environment. Ecosystems can be small, such as the tide pools found near the rocky shores of many oceans, or large, such as the Amazon Rainforest in Brazil (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)).

There are three broad categories of ecosystems based on their general environment: freshwater, ocean water, and terrestrial. Within these broad categories are individual ecosystem types based on the organisms present and the type of environmental habitat.

Ocean ecosystems are the most common, comprising 75 percent of the Earth's surface and consisting of three basic types: shallow ocean, deep ocean water, and deep ocean surfaces (the low depth areas of the deep oceans). The shallow ocean ecosystems include extremely biodiverse coral reef ecosystems, and the deep ocean surface is known for its large numbers of plankton and krill (small crustaceans) that support it. These two environments are especially important to aerobic respirators worldwide as the phytoplankton perform 40 percent of all photosynthesis on Earth. Although not as diverse as the other two, deep ocean ecosystems contain a wide variety of marine organisms. Such ecosystems exist even at the bottom of the ocean where light is unable to penetrate through the water.

Freshwater ecosystems are the rarest, occurring on only 1.8 percent of the Earth's surface. Lakes, rivers, streams, and springs comprise these systems; they are quite diverse, and they support a variety of fish, amphibians, reptiles, insects, phytoplankton, fungi, and bacteria.

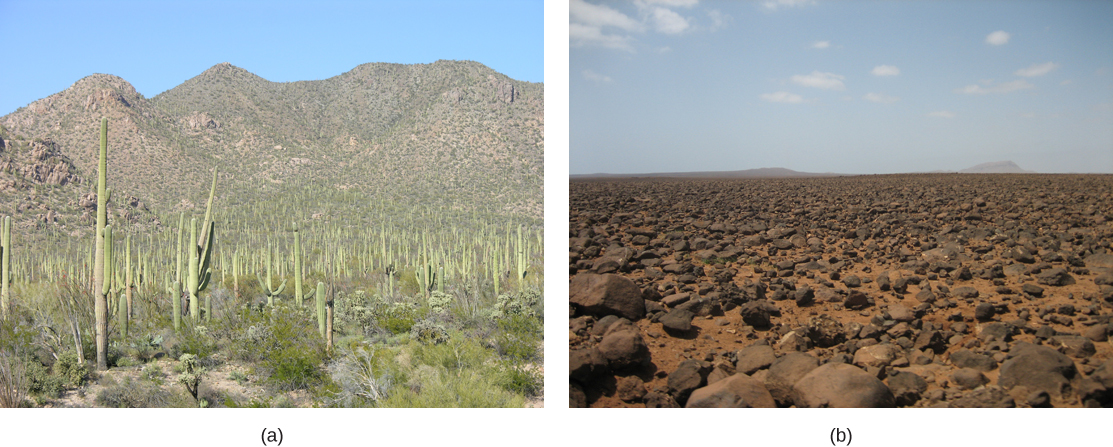

Terrestrial ecosystems, also known for their diversity, are grouped into large categories called biomes, such as tropical rain forests, savannas, deserts, coniferous forests, deciduous forests, and tundra. Grouping these ecosystems into just a few biome categories obscures the great diversity of the individual ecosystems within them. For example, there is great variation in desert vegetation: the saguaro cacti and other plant life in the Sonoran Desert, in the United States, are relatively abundant compared to the desolate rocky desert of Boa Vista, an island off the coast of Western Africa (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)).

Ecosystems are complex with many interacting parts. They are routinely exposed to various disturbances, or changes in the environment that effect their compositions: yearly variations in rainfall and temperature and the slower processes of plant growth, which may take several years. Many of these disturbances are a result of natural processes. For example, when lightning causes a forest fire and destroys part of a forest ecosystem, the ground is eventually populated by grasses, then by bushes and shrubs, and later by mature trees, restoring the forest to its former state. The impact of environmental disturbances caused by human activities is as important as the changes wrought by natural processes. Human agricultural practices, air pollution, acid rain, global deforestation, overfishing, eutrophication, oil spills, and illegal dumping on land and into the ocean are all issues of concern to conservationists.

Equilibrium is the steady state of an ecosystem where all organisms are in balance with their environment and with each other. In ecology, two parameters are used to measure changes in ecosystems: resistance and resilience. The ability of an ecosystem to remain at equilibrium in spite of disturbances is called resistance. The speed at which an ecosystem recovers equilibrium after being disturbed, called its resilience. Ecosystem resistance and resilience are especially important when considering human impact. The nature of an ecosystem may change to such a degree that it can lose its resilience entirely. This process can lead to the complete destruction or irreversible altering of the ecosystem.

Evolution Connection: Three-spined Stickleback

It is well established by the theory of natural selection that changes in the environment play a major role in the evolution of species within an ecosystem. However, little is known about how the evolution of species within an ecosystem can alter the ecosystem environment. In 2009, Dr. Luke Harmon, from the University of Idaho in Moscow, published a paper that for the first time showed that the evolution of organisms into subspecies can have direct effects on their ecosystem environment.1

The three-spines stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus) is a freshwater fish that evolved from a saltwater fish to live in freshwater lakes about 10,000 years ago, which is considered a recent development in evolutionary time (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). Over the last 10,000 years, these freshwater fish then became isolated from each other in different lakes. Depending on which lake population was studied, findings showed that these sticklebacks then either remained as one species or evolved into two species. The divergence of species was made possible by their use of different areas of the pond for feeding called micro niches.

Dr. Harmon and his team created artificial pond microcosms in 250-gallon tanks and added muck from freshwater ponds as a source of zooplankton and other invertebrates to sustain the fish. In different experimental tanks they introduced one species of stickleback from either a single-species or double-species lake.

Over time, the team observed that some of the tanks bloomed with algae while others did not. This puzzled the scientists, and they decided to measure the water's dissolved organic carbon (DOC), which consists of mostly large molecules of decaying organic matter that give pond-water its slightly brownish color. It turned out that the water from the tanks with two-species fish contained larger particles of DOC (and hence darker water) than water with single-species fish. This increase in DOC blocked the sunlight and prevented algal blooming. Conversely, the water from the single-species tank contained smaller DOC particles, allowing more sunlight penetration to fuel the algal blooms.

This change in the environment, which is due to the different feeding habits of the stickleback species in each lake type, probably has a great impact on the survival of other species in these ecosystems, especially other photosynthetic organisms. Thus, the study shows that, at least in these ecosystems, the environment and the evolution of populations have reciprocal effects that may now be factored into simulation models.

Research into Ecosystem Dynamics: Ecosystem Experimentation and Modeling

The study of the changes in ecosystem structure caused by changes in the environment (disturbances) or by internal forces is called ecosystem dynamics. Ecosystems are characterized using a variety of research methodologies. Some ecologists study ecosystems using controlled experimental systems, while some study entire ecosystems in their natural state, and others use both approaches.

A holistic ecosystem model attempts to quantify the composition, interaction, and dynamics of entire ecosystems; it is the most representative of the ecosystem in its natural state. A food web is an example of a holistic ecosystem model. However, this type of study is limited by time and expense, as well as the fact that it is neither feasible nor ethical to do experiments on large natural ecosystems. To quantify all different species in an ecosystem and the dynamics in their habitat is difficult, especially when studying large habitats such as the Amazon Rainforest, which covers 1.4 billion acres (5.5 million km2) of the Earth’s surface.

For these reasons, scientists study ecosystems under more controlled conditions. Experimental systems usually involve either partitioning a part of a natural ecosystem that can be used for experiments, termed a mesocosm, or by re-creating an ecosystem entirely in an indoor or outdoor laboratory environment, which is referred to as a microcosm. A major limitation to these approaches is that removing individual organisms from their natural ecosystem or altering a natural ecosystem through partitioning may change the dynamics of the ecosystem. These changes are often due to differences in species numbers and diversity and also to environment alterations caused by partitioning (mesocosm) or re-creating (microcosm) the natural habitat. Thus, these types of experiments are not totally predictive of changes that would occur in the ecosystem from which they were gathered.

As both of these approaches have their limitations, some ecologists suggest that results from these experimental systems should be used only in conjunction with holistic ecosystem studies to obtain the most representative data about ecosystem structure, function, and dynamics.

Scientists use the data generated by these experimental studies to develop ecosystem models that demonstrate the structure and dynamics of ecosystems. Three basic types of ecosystem modeling are routinely used in research and ecosystem management: a conceptual model, an analytical model, and a simulation model. A conceptual model is an ecosystem model that consists of flow charts to show interactions of different compartments of the living and nonliving components of the ecosystem. A conceptual model describes ecosystem structure and dynamics and shows how environmental disturbances affect the ecosystem; however, its ability to predict the effects of these disturbances is limited. Analytical and simulation models, in contrast, are mathematical methods of describing ecosystems that are indeed capable of predicting the effects of potential environmental changes without direct experimentation, although with some limitations as to accuracy. An analytical model is an ecosystem model that is created using simple mathematical formulas to predict the effects of environmental disturbances on ecosystem structure and dynamics. A simulation model is an ecosystem model that is created using complex computer algorithms to holistically model ecosystems and to predict the effects of environmental disturbances on ecosystem structure and dynamics. Ideally, these models are accurate enough to determine which components of the ecosystem are particularly sensitive to disturbances, and they can serve as a guide to ecosystem managers (such as conservation ecologists or fisheries biologists) in the practical maintenance of ecosystem health.

Conceptual Models

Conceptual models are useful for describing ecosystem structure and dynamics and for demonstrating the relationships between different organisms in a community and their environment. Conceptual models are usually depicted graphically as flow charts. The organisms and their resources are grouped into specific compartments with arrows showing the relationship and transfer of energy or nutrients between them. Thus, these diagrams are sometimes called compartment models.

To model the cycling of mineral nutrients, organic and inorganic nutrients are subdivided into those that are bioavailable (ready to be incorporated into biological macromolecules) and those that are not. For example, in a terrestrial ecosystem near a deposit of coal, carbon will be available to the plants of this ecosystem as carbon dioxide gas in a short-term period, not from the carbon-rich coal itself. However, over a longer period, microorganisms capable of digesting coal will incorporate its carbon or release it as natural gas (methane, CH4), changing this unavailable organic source into an available one. This conversion is greatly accelerated by the combustion of fossil fuels by humans, which releases large amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. This is thought to be a major factor in the rise of the atmospheric carbon dioxide levels in the industrial age. The carbon dioxide released from burning fossil fuels is produced faster than photosynthetic organisms can use it. This process is intensified by the reduction of photosynthetic trees because of worldwide deforestation. Most scientists agree that high atmospheric carbon dioxide is a major cause of global climate change.

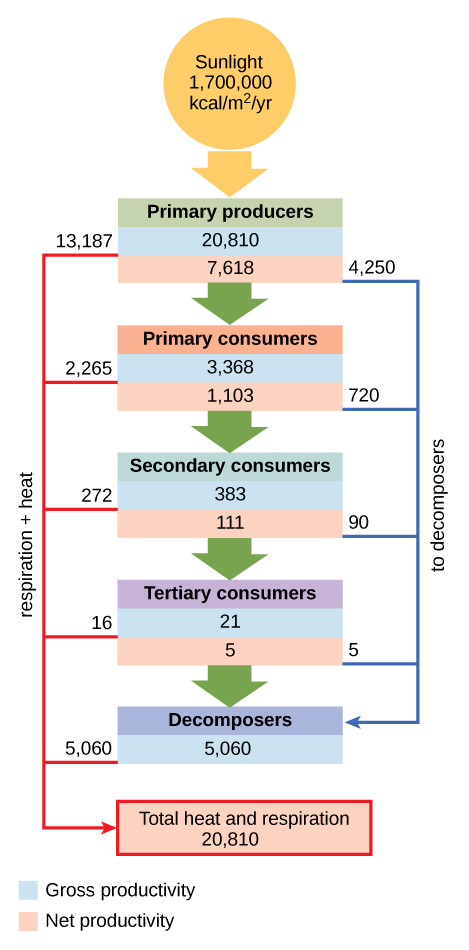

Conceptual models are also used to show the flow of energy through particular ecosystems. Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) is based on Howard T. Odum’s classical study of the Silver Springs, Florida, holistic ecosystem in the mid-twentieth century.2 This study shows the energy content and transfer between various ecosystem compartments.

Analytical and Simulation Models

The major limitation of conceptual models is their inability to predict the consequences of changes in ecosystem species and/or environment. Ecosystems are dynamic entities and subject to a variety of abiotic and biotic disturbances caused by natural forces and/or human activity. Ecosystems altered from their initial equilibrium state can often recover from such disturbances and return to a state of equilibrium. As most ecosystems are subject to periodic disturbances and are often in a state of change, they are usually either moving toward or away from their equilibrium state. There are many of these equilibrium states among the various components of an ecosystem, which affects the ecosystem overall. Furthermore, as humans have the ability to greatly and rapidly alter the species content and habitat of an ecosystem, the need for predictive models that enable understanding of how ecosystems respond to these changes becomes more crucial.

Analytical models often use simple, linear components of ecosystems, such as food chains, and are known to be complex mathematically; therefore, they require a significant amount of mathematical knowledge and expertise. Although analytical models have great potential, their simplification of complex ecosystems is thought to limit their accuracy. Simulation models that use computer programs are better able to deal with the complexities of ecosystem structure.

A recent development in simulation modeling uses supercomputers to create and run individual-based simulations, which accounts for the behavior of individual organisms and their effects on the ecosystem as a whole. These simulations are considered to be the most accurate and predictive of the complex responses of ecosystems to disturbances.

Landscape Ecology

Landscapes (or seascapes in the marine context) are a mosaic of “patches”, each of which represents an ecological community. A landscape may contain various kinds of communities for the following reasons:

- each community reflects particular environmental conditions, such as different soil or bedrock types or variations of standing water (as in lakes, streams, or wetlands)

- the communities represent various stages in succession, such as patches of different age after wildfire or insect damage

- the communities may be related to land-use, as when parts of landscapes are affected by urbanization, agriculture, forestry, roads, or other human influences.

Over time, the spatial patterns of communities on landscapes are highly dynamic. This largely reflects the influence of disturbances and successional recovery. A patch that today is a pasture, a recent clear-cut, or a burn may be a mature forest after 50 years of succession. Similarly, a pond may in-fill over the centuries and become a wetland, which with further time may succeed into a forest. Ecologists use the term “shifting mosaic” to integrate the spatial and temporal variations of communities on landscapes. The following factors affect the shifting mosaic of communities.

- Patch size relates to the area of particular stands of communities (a stand is a community in a specific place). All species need some minimal area of habitat to support their populations, and small patches may not be adequate for that purpose. Relatively small patches may, however, help to support a population living in several stands on the landscape (an extensive population of this sort is known as a metapopulation). This can happen if the patches are connected by corridors to other suitable habitat, or if the species is capable of dispersing through surrounding inhospitable habitat (for this to occur, the landscape matrix must be permeable to movements of the species).

- The amount of edge is important because it influences the length of ecotone (transitional) habitat associated with a patch. A circular patch has the smallest ratio of edge to area, and smaller patches have higher ratios than larger ones of the same shape. An ecotone between patch types is a particular kind of habitat, and it may be selectively used by “edge species.” However, the greater the ratio of edge to area, the less “interior” habitat there is (this is uninfluenced by ecological conditions associated with an ecotone). Ecologists have identified “interior species” that are less successful if they try to use habitat close to an edge. Certain forest birds, for example, experience greater rates of predation and nest parasitism in small remnants of mature forest.

- Connectedness refers to the presence of links between otherwise discrete patches of similar habitat. These links may be used by a species as corridors to move among patches, allowing their metapopulation to function on the landscape. As was noted previously, connectedness is also related to the ability of a species to disperse among habitable patches through the surrounding habitat.

- Age-class adjacency is important in a landscape in which patches represent different stages of a successional sequence. This commonly occurs in landscapes affected by disturbances such as wildfire, insect epidemics, or clear-cutting. In general, patches of a similar post-disturbance age will be comparable in many aspects of habitat, while those of different age will be less similar. This can be an important consideration for movements of species among isolated patches that are suitable as habitat.

- Complex habitat requirements are characteristic of some larger animals, such as deer, bear, and wolf. These species need different kinds of habitat patches for specific purposes at various times of year. Because these animals participate in various kinds of communities, all of the habitat patches they need must be present on the landscape if a viable metapopulation is to be sustained.

- Landscape-level biodiversity is related to the richness of community types over a large area. A landscape that is uniformly covered by a single community has less biodiversity at this scale than one composed of a rich and dynamic mosaic of different kinds of communities.

- Landscape-level functions operate over extensive areas, and they may integrate the influences of many kinds of communities. A watershed, for example, is the expanse of terrain from which water drains into a stream, lake, or some other waterbody. Most watersheds contain various kinds of habitat patches, each with particular influences on hydrology and water chemistry. In general, watersheds covered with mature forest yield the cleanest flows of water. Other environmental services provided by well-vegetated landscapes include evapotranspiration, control of erosion, moderation of climatic extremes, and absorption of atmospheric carbon dioxide and release of oxygen.

Landscape ecology is an important subject area in environmental science. Humans commonly affect individual stands of particular kinds of communities, but many of the ecological effects must be managed at the scale of landscapes and seascapes.

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\): A landscape is a mosaic of various kinds of communities, each stand of which represent a patch. In addition, landscapes are subjected to patch dynamics associated with natural disturbances, such as wildfire, windstorms, and insect outbreaks. However, the patch dynamics of many forested landscapes are being increasingly structured by forestry. In this aerial view of an area in New Brunswick, the natural forest is being harvested by clear-cutting (the lighter patches are snow in clear-cuts), which initiates a succession that restores a forest for another harvest in 60-80 years. Unless some areas are set aside for protection, this entire landscape may become used in this way. Source: M. Sullivan.

Footnotes

- 1 Nature (Vol. 458, April 1, 2009)

- 2 Howard T. Odum, “Trophic Structure and Productivity of Silver Springs, Florida,” Ecological Monographs 27, no. 1 (1957): 47–112.

Contributors and Attributions

Modified by Kyle Whittinghill from the following sources

- 46.1: Ecology of Ecosystems by OpenStax, is licensed CC BY by

Connie Rye (East Mississippi Community College), Robert Wise (University of Wisconsin, Oshkosh), Vladimir Jurukovski (Suffolk County Community College), Jean DeSaix (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill), Jung Choi (Georgia Institute of Technology), Yael Avissar (Rhode Island College) among other contributing authors. Original content by OpenStax (CC BY 4.0; Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/185cbf87-c72...f21b5eabd@9.87).

- Essentials of Environmental Science by Kamala Doršner is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

- Ecology: From Individuals to the Biosphere from Environmental Science: A Canadian Perspective by Bill Freedman