2020_Spring_Bis2A_Facciotti_Lecture_14

- Page ID

- 27856

Learning objectives associated with 2020_Spring_Bis2A_Facciotti_Lecture_14

|

Fermentation and regeneration of NAD+

Section summary

This section discusses the process of fermentation. Due to the heavy emphasis in this course on central carbon metabolism, the discussion of fermentation understandably focuses on the fermentation of pyruvate. Nevertheless, some of the core principles that we cover in this section apply equally well to the fermentation of many other small molecules.

The "purpose" of fermentation

The oxidation of a variety of small organic compounds is a process that is utilized by many organisms to garner energy for cellular maintenance and growth. The oxidation of glucose via glycolysis is one such pathway. Several key steps in the oxidation of glucose to pyruvate involve the reduction of the electron/energy shuttle NAD+ to NADH. You were already asked to figure out what options the cell might reasonably have to reoxidize the NADH to NAD+ in order to avoid consuming the available pools of NAD+ and to thus avoid stopping glycolysis. Put differently, during glycolysis, cells can generate large amounts of NADH and slowly exhaust their supplies of NAD+. If glycolysis is to continue, the cell must find a way to regenerate NAD+, either by synthesis or by some form of recycling.

In the absence of any other process—that is, if we consider glycolysis alone—it is not immediately obvious what the cell might do. One choice is to try putting the electrons that were once stripped off of the glucose derivatives right back onto the downstream product, pyruvate, or one of its derivatives. We can generalize the process by describing it as the returning of electrons to the molecule that they were once removed, usually to restore pools of an oxidizing agent. This, in short, is fermentation. As we will discuss in a different section, the process of respiration can also regenerate the pools of NAD+ from NADH. Cells lacking respiratory chains or in conditions where using the respiratory chain is unfavorable may choose fermentation as an alternative mechanism for garnering energy from small molecules.

An example: lactic acid fermentation

An everyday example of a fermentation reaction is the reduction of pyruvate to lactate by the lactic acid fermentation reaction. This reaction should be familiar to you: it occurs in our muscles when we exert ourselves during exercise. When we exert ourselves, our muscles require large amounts of ATP to perform the work we are demanding of them. As the ATP is consumed, the muscle cells are unable to keep up with the demand for respiration, O2 becomes limiting, and NADH accumulates. Cells need to get rid of the excess and regenerate NAD+, so pyruvate serves as an electron acceptor, generating lactate and oxidizing NADH to NAD+. Many bacteria use this pathway as a way to complete the NADH/NAD+ cycle. You may be familiar with this process from products like sauerkraut and yogurt. The chemical reaction of lactic acid fermentation is the following:

Pyruvate + NADH ↔ lactic acid + NAD+

Figure 1. Lactic acid fermentation converts pyruvate (a slightly oxidized carbon compound) to lactic acid. In the process, NADH is oxidized to form NAD+. Attribution: Marc T. Facciotti (original work)

Energy story for the fermentation of pyruvate to lactate

An example (if a bit lengthy) energy story for lactic acid fermentation is the following:

The reactants are pyruvate, NADH, and a proton. The products are lactate and NAD+. The process of fermentation results in the reduction of pyruvate to form lactic acid and the oxidation of NADH to form NAD+. Electrons from NADH and a proton are used to reduce pyruvate into lactate. If we examine a table of standard reduction potential, we see under standard conditions that a transfer of electrons from NADH to pyruvate to form lactate is exergonic and thus thermodynamically spontaneous. The reduction and oxidation steps of the reaction are coupled and catalyzed by the enzyme lactate dehydrogenase.

A second example: alcohol fermentation

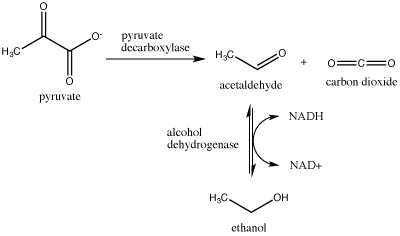

Another familiar fermentation process is alcohol fermentation, which produces ethanol, an alcohol. The alcohol fermentation reaction is the following:

Figure 2. Ethanol fermentation is a two-step process. Pyruvate (pyruvic acid) is first converted into carbon dioxide and acetaldehyde. The second step converts acetaldehyde to ethanol and oxidizes NADH to NAD+. Attribution: Marc T. Facciotti (original work)

In the first reaction, a carboxyl group is removed from pyruvic acid, releasing carbon dioxide as a gas (some of you may be familiar with this as a key component of various beverages). The second reaction removes electrons from NADH, forming NAD+ and producing ethanol (another familiar compound—usually in the same beverage) from the acetaldehyde, which accepts the electrons.

Fermentation pathways are numerous

While the lactic acid fermentation and alcohol fermentation pathways described above are examples, there are many more reactions (too numerous to go over) that Nature has evolved to complete the NADH/NAD+ cycle. It is important that you understand the general concepts behind these reactions. In general, cells try to maintain a balance or constant ratio between NADH and NAD+; when this ratio becomes unbalanced, the cell compensates by modulating other reactions to compensate. The only requirement for a fermentation reaction is that it uses a small organic compound as an electron acceptor for NADH and regenerates NAD+. Other familiar fermentation reactions include ethanol fermentation (as in beer and bread), propionic fermentation (it's what makes the holes in Swiss cheese), and malolactic fermentation (it's what gives Chardonnay its more mellow flavor—the more conversion of malate to lactate, the softer the wine). In Figure 3, you can see a large variety of fermentation reactions that various bacteria use to reoxidize NADH to NAD+. All of these reactions start with pyruvate or a derivative of pyruvate metabolism, such as oxaloacetate or formate. Pyruvate is produced from the oxidation of sugars (glucose or ribose) or other small, reduced organic molecules. It should also be noted that other compounds can be used as fermentation substrates besides pyruvate and its derivatives. These include methane fermentation, sulfide fermentation, or the fermentation of nitrogenous compounds such as amino acids. You are not expected to memorize all of these pathways. You are, however, expected to recognize a pathway that returns electrons to products of the compounds that were originally oxidized to recycle the NAD+/NADH pool and to associate that process with fermentation.

Figure 3. This figure shows various fermentation pathways using pyruvate as the initial substrate. In the figure, pyruvate is reduced to a variety of products via different and sometimes multistep (dashed arrows represent possible multistep processes) reactions. All details are deliberately not shown. The key point is to appreciate that fermentation is a broad term not solely associated with the conversion of pyruvate to lactic acid or ethanol. Source: Marc T. Facciotti (original work)

A note on the link between substrate-level phosphorylation and fermentation

Fermentation occurs in the absence of molecular oxygen (O2). It is an anaerobic process. Notice there is no O2 in any of the fermentation reactions shown above. Many of these reactions are quite ancient, hypothesized to be some of the first energy-generating metabolic reactions to evolve. This makes sense if we consider the following:

- The early atmosphere was highly reduced, with little molecular oxygen readily available.

- Small, highly reduced organic molecules were relatively available, arising from a variety of chemical reactions.

- These types of reactions, pathways, and enzymes are found in many different types of organisms, including bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes, suggesting these are very ancient reactions.

- The process evolved long before O2 was found in the environment.

- The substrates, highly reduced, small organic molecules, like glucose, were readily available.

- The end products of many fermentation reactions are small organic acids, produced by the oxidation of the initial substrate.

- The process is coupled to substrate-level phosphorylation reactions. That is, small, reduced organic molecules are oxidized, and ATP is generated by first a red/ox reaction followed by the substrate-level phosphorylation.

- This suggests that substrate-level phosphorylation and fermentation reactions coevolved.

Consequences of fermentation

Imagine a world where fermentation is the primary mode for extracting energy from small molecules. As populations thrive, they reproduce and consume the abundance of small, reduced organic molecules in the environment, producing acids. One consequence is the acidification (decrease in pH) of the environment, including the internal cellular environment. This can be disruptive, since changes in pH can have a profound influence on the function and interactions among various biomolecules. Therefore, mechanisms needed to evolve that could remove the various acids. Fortunately, in an environment rich in reduced compounds, substrate-level phosphorylation and fermentation can produce large quantities of ATP.

It is hypothesized that this scenario was the beginning of the evolution of the F0F1-ATPase, a molecular machine that hydrolyzes ATP and translocates protons across the membrane (we'll see this again in the next section). With the F0F1-ATPase, the ATP produced from fermentation could now allow for the cell to maintain pH homeostasis by coupling the free energy of hydrolysis of ATP to the transport of protons out of the cell. The downside is that cells are now pumping all of these protons into the environment, which will now start to acidify.

Oxidation of Pyruvate and the TCA Cycle

Overview of Pyruvate Metabolism and the TCA Cycle

Under

The different fates of pyruvate and other end products of glycolysis

The glycolysis module left off with the end-products of glycolysis: 2 pyruvate molecules, 2 ATPs and 2 NADH molecules. This module and the module on fermentation explore what the cell can do with the pyruvate, ATP and NADH that

The fates of ATP and NADH

ATP can

What to do with the

The fate of cellular pyruvate

- Pyruvate can be a terminal electron acceptor (either directly or indirectly) in fermentation

reactions and we discuss this in the fermentation module. Pyruvate can be secreted from the cell as a waste product.- Pyruvate can

be further oxidized to extract more free energy from this fuel. - Pyruvate can serve as a valuable intermediate compound linking some core carbon processing metabolic

pathways

The further oxidation of pyruvate

In respiring bacteria and archaea, the pyruvate is further oxidized in the cytoplasm. In aerobically respiring eukaryotic cells, cells transport the pyruvate molecules produced at the end of glycolysis into mitochondria. These sites of cellular respiration house oxygen consuming electron transport chains (ETC in the module on respiration and electron transport). Organisms from all three domains of life share similar mechanisms to further oxidize the pyruvate to CO2. First pyruvate

Conversion of Pyruvate into Acetyl-CoA

In a multi-step reaction

In the presence of a suitable terminal electron acceptor, acetyl

The Tricarboxcylic Acid (TCA) Cycle

In bacteria and archaea reactions in the TCA cycle typically happen in the cytosol. In eukaryotes, the TCA cycle takes place in the matrix of mitochondria. Almost all (but not all) of the enzymes of the TCA cycle are water soluble (not in the membrane), with the single exception of the enzyme succinate dehydrogenase, which

Figure 2. In the TCA cycle, the acetyl group from acetyl

Attribution: “

We are explicitly referring to eukaryotes, bacteria and archaea when we discuss the location of the TCA cycle because many beginning students of biology only associate the TCA cycle with mitochondria. Yes, the TCA cycle occurs in the mitochondria of eukaryotic cells. However, this pathway is not exclusive to eukaryotes;

Steps in the TCA Cycle

Step 1:

The first step of the cycle is a condensation reaction involving the two-carbon acetyl group of acetyl-

Step 2:

In step two, citrate loses one water molecule and gains another as citrate converts into its isomer, isocitrate.

Step 3:

In step three, isocitrate

Step 4:

Step 4

Possible NB Discussion  Point

Point

We have seen several steps in this and other pathways that

Step 5:

In step five, a substrate level phosphorylation event occurs. Here, an inorganic phosphate (Pi)

Step 6:

Step six is another red/ox

Step 7:

Water

Summary

Note that this process (oxidation of pyruvate to Acetyl-

Connections to Carbon Flow

One hypothesis that we have explored in this reading and in class is the idea that "central metabolism" evolved to generate carbon precursors for catabolic reactions. Our hypothesis also states that as cells evolved, these reactions became linked into pathways: glycolysis and the TCA cycle, to maximize their effectiveness for the cell. We can postulate that a side benefit to evolving this metabolic pathway was the generation of NADH from the complete oxidation of glucose - we saw the beginning of this idea when we discussed fermentation. We have already discussed how glycolysis not only provides ATP from substrate level phosphorylation but also yields a net of 2 NADH molecules and 6 essential precursors: glucose-6-P, fructose-6-P, 3-phosphoglycerate, phosphoenolpyruvate, and pyruvate. While ATP can

During the process of pyruvate oxidation via the TCA cycle,

Possible NB Discussion  Point

Point

Additional Links

Here are some additional links to videos and pages that you may find useful.

Chemwiki Links

Chemwiki TCA cycle - link down untilkey content corrections are made to the resource