Passive Transport

- Page ID

- 50634

Energetics of transport

All substances that move through the membrane do so by one of two general methods, which are categorized based on whether the transport process is exergonic or endergonic. Passive transport is the exergonic movement of substances across the membrane. In contrast, active transport is the endergonic movement of substances across the membrane that is coupled to an exergonic reaction.

Passive Transport

Passive transport does not require the cell to expend energy. In passive transport, substances move from an area of higher concentration to an area of lower concentration, down the concentration gradient and energetically favorable. Depending on the chemical nature of the substance, different processes may be associated with passive transport.

Diffusion

Diffusion is a passive process of transport. A single substance tends to move from an area of high concentration to an area of low concentration until the concentration is equal across a space. You are familiar with diffusion of substances through the air. For example, think about someone opening a bottle of ammonia in a room filled with people. The ammonia gas is at its highest concentration in the bottle; its lowest concentration is at the edges of the room. The ammonia vapor will diffuse, or spread away, from the bottle, and gradually, more and more people will smell the ammonia as it spreads. Materials move within the cell’s cytosol by diffusion, and certain materials move through the plasma membrane by diffusion.

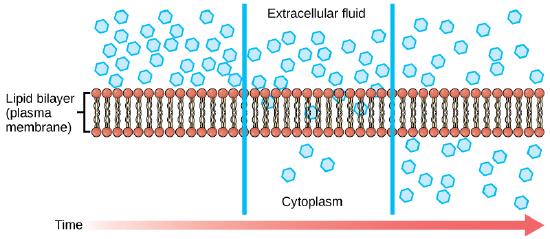

Figure 1. Diffusion through a permeable membrane moves a substance from an area of high concentration (extracellular fluid, in this case) down its concentration gradient (into the cytoplasm). Each separate substance in a medium, such as the extracellular fluid, has its own concentration gradient, independent of the concentration gradients of other materials. In addition, each substance will diffuse according to that gradient. Within a system, there will be different rates of diffusion of the different substances in the medium (Attribution: Mariana Ruiz Villareal, modified)

Factors That Affect Diffusion

If unconstrained, molecules will move through and explore space randomly at a rate that depends on their size, their shape, their environment, and their thermal energy. This type of movement underlies the diffusive movement of molecules through whatever medium they are in. The absence of a concentration gradient does not mean that this movement will stop, just that there may be no net movement of the number of molecules from one area to another, a condition known as dynamic equilibrium.

Factors influencing diffusion include:

- Extent of the concentration gradient: The greater the difference in concentration, the more rapid the diffusion. The closer the distribution of the material gets to equilibrium, the slower the rate of diffusion becomes.

- Shape, size and mass of the molecules diffusing: Large and heavier molecules move more slowly; therefore, they diffuse more slowly. The reverse is typically true for smaller, lighter molecules.

- Temperature: Higher temperatures increase the energy and therefore the movement of the molecules, increasing the rate of diffusion. Lower temperatures decrease the energy of the molecules, thus decreasing the rate of diffusion.

- Solvent density: As the density of a solvent increases, the rate of diffusion decreases. The molecules slow down because they have a more difficult time getting through the denser medium. If the medium is less dense, rates of diffusion increase. Since cells primarily use diffusion to move materials within the cytoplasm, any increase in the cytoplasm’s density will decrease the rate at which materials move in the cytoplasm.

- Solubility: As discussed earlier, nonpolar or lipid-soluble materials pass through plasma membranes more easily than polar materials, allowing a faster rate of diffusion.

- Surface area and thickness of the plasma membrane: Increased surface area increases the rate of diffusion, whereas a thicker membrane reduces it.

- Distance travelled: The greater the distance that a substance must travel, the slower the rate of diffusion. This places an upper limitation on cell size. A large, spherical cell will die because nutrients or waste cannot reach or leave the center of the cell, respectively. Therefore, cells must either be small in size, as in the case of many prokaryotes, or be flattened, as with many single-celled eukaryotes.

Facilitated transport

In facilitated transport, also called facilitated diffusion, materials diffuse across the plasma membrane with the help of membrane proteins. A concentration gradient exists that allows these materials to diffuse into or out of the cell without expending cellular energy. In the case that the materials are ions or polar molecules, compounds that are repelled by the hydrophobic parts of the cell membrane, facilitated transport proteins help shield these materials from the repulsive force of the membrane, allowing them to diffuse into the cell.

Possible NB Discussion  Point

Point

Compare and contrast passive diffusion and facilitated diffusion.

Channels

The integral proteins involved in facilitated transport are collectively referred to as transport proteins, and they function as either channels for the material or carriers. In both cases, they are transmembrane proteins. Different channel proteins have different transport properties. Some have evolved to be have very high specificity for the substance that is being transported while others transport a variety of molecules sharing some common characteristic(s). The interior "passageway" of channel proteins have evolved to provide a low energetic barrier for transport of substances across the membrane through the complementary arrangement of amino acid functional groups (of both backbone and side-chains). Passage through the channel allows polar compounds to avoid the nonpolar central layer of the plasma membrane that would otherwise slow or prevent their entry into the cell. While at any one time significant amounts of water crosses the membrane both in and out the rate of individual water molecule transport may not be fast enough to adapt to changing environmental conditions. For such cases Nature has evolved a special class of membrane proteins called aquaporins that allow water to pass through the membrane at a very high rate.

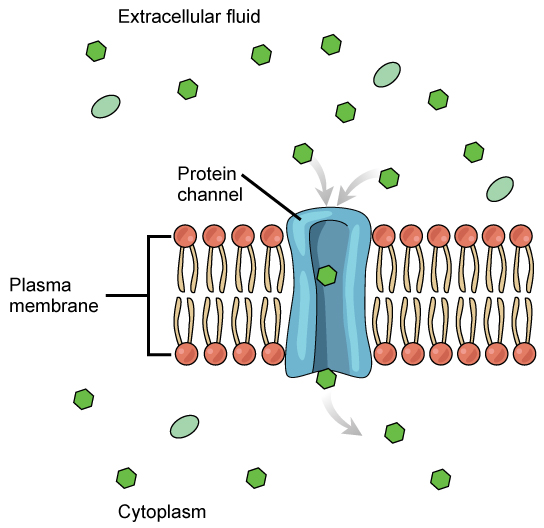

Figure 2: Facilitated transport moves substances down their concentration gradients. They may cross the plasma membrane with the aid of channel proteins. (Attribution: Mariana Ruiz Villareal, modified.)

Channel proteins are either open at all times or they are “gated.” The latter controls the opening of the channel. Various mechanisms may be involved in the gating mechanism. For instance, the attachment of a specific ion or small molecule to the channel protein may trigger opening. Changes in local membrane "stress" or changes in voltage across the membrane may also be triggers to open or close a channel.

Different organisms and tissues in multicellular species express different sets of channel proteins in their membranes depending on the environments they live in or specialized function they play in an organisms. This provides each type of cell with a unique membrane permeability profile that is evolved to complement its "needs" (note the anthropomorphism). For example, in some tissues, sodium and chloride ions pass freely through open channels, whereas in other tissues a gate must be opened to allow passage. This occurs in the kidney, where both forms of channels are found in different parts of the renal tubules. Cells involved in the transmission of electrical impulses, such as nerve and muscle cells, have gated channels for sodium, potassium, and calcium in their membranes. Opening and closing of these channels changes the relative concentrations on opposing sides of the membrane of these ions, resulting a change in electrical potential across the membrane that lead to message propagation in the case of nerve cells or in muscle contraction in the case of muscle cells.

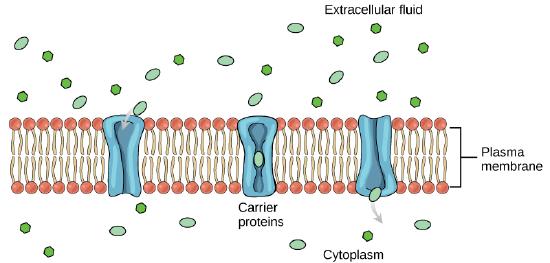

Carrier Proteins

Another type of protein embedded in the plasma membrane is a carrier protein. This aptly named protein binds a substance and, in doing so, triggers a change of its own shape, moving the bound molecule from the outside of the cell to its interior; depending on the gradient, the material may move in the opposite direction. Carrier proteins are typically specific for a single substance. This selectivity adds to the overall selectivity of the plasma membrane. The molecular-scale mechanism of function for these proteins remains poorly understood.

Carrier proteins play an important role in the function of kidneys. Glucose, water, salts, ions, and amino acids needed by the body are filtered in one part of the kidney. This filtrate, which includes glucose, is then reabsorbed in another part of the kidney with the help of carrier proteins. Because there are only a finite number of carrier proteins for glucose, if more glucose is present in the filtrate than the proteins can handle, the excess is not reabsorbed and it is excreted from the body in the urine. In a diabetic individual, this is described as “spilling glucose into the urine.” A different group of carrier proteins called glucose transport proteins, or GLUTs, are involved in transporting glucose and other hexose sugars through plasma membranes within the body.

Channel and carrier proteins transport materials at different rates. Channel proteins transport much more quickly than do carrier proteins. Channel proteins facilitate diffusion at a rate of tens of millions of molecules per second, whereas carrier proteins work at a rate of a thousand to a million molecules per second.

Note: A note of appreciation

The rates of transport just discussed are astounding. Recall that these molecular catalysts are on the scale of 10s of nanometers (10-9 meters) and that they are composed of a self-folding string of 20 amino acids and the relatively small selection of chemical functional groups that they carry.