Introduction to Respiration and Electron Transport Chains

General Overview and Points to Keep In Mind

In the next few modules, we learn about the process of respiration and the roles that electron transport chains play in this process. A definition of the word "respiration" that most people are familiar with is "the act of breathing". When we breathe, we bring air, including molecular oxygen, into our lungs from outside of the body. The oxygen then becomes reduced, and waste products, including the reduced oxygen in the form of water, are exhaled. More generically, some reactant comes into the organism and then gets reduced and leaves the body as a waste product.

This generic idea, in a nutshell, can be applied across biology. Note that oxygen need not always be the compound that is brought in, reduced, and dumped as waste. The compounds onto which the electrons that are "dumped" are known as "terminal electron acceptors." The molecules from which the electrons originate vary across biology (so far, we have only looked at one source - the reduced carbon-based molecule glucose).

In between the original electron source and the terminal electron acceptor are a series of biochemical reactions involving at least one redox reaction. These redox reactions harvest energy for the cell by coupling an exergonic redox reaction to an energy-requiring reaction in the cell. In respiration, a special set of enzymes carry out a linked series of redox reactions that ultimately transfer electrons to the terminal electron acceptor.

These "chains" of redox enzymes and electron carriers are called electron transport chains (ETC). In aerobically respiring eukaryotic cells the ETC is composed of four large, multi-protein complexes embedded in the inner mitochondrial membrane and two small diffusible electron carriers shuttling electrons between them. Electrons pass from enzyme to enzyme through a series of redox reactions. These reactions couple exergonic redox reactions to the endergonic transport of hydrogen ions across the inner mitochondrial membrane. This process contributes to the creation of a transmembrane electrochemical gradient. The electrons passing through the ETC gradually lose potential energy until the point the ETC deposits them on the terminal electron acceptor. The cell typically disposes of the reduced terminal electron as waste. When oxygen acts as the final electron acceptor, the free energy difference of this multi-step redox process is ~ -60 kcal/mol when NADH donates electrons or ~ -45 kcal/mol when FADH2 donates.

Note: Oxygen is not the only terminal electron acceptor in nature

Recall, that we use oxygen as an example of only one of many possible terminal electron acceptors that can be found in nature. The free energy differences associated with respiration in anaerobic organisms will be different.

In prior modules we discussed the general concept of redox reactions in biology and introduced the Electron Tower, a tool to help you understand redox chemistry and to estimate the direction and magnitude of potential energy differences for various redox couples. In later modules, substrate level phosphorylation and fermentation were discussed, and we saw that enzymes could directly couple exergonic redox reactions to the endergonic synthesis of ATP.

We hypothesize these processes to be one of the oldest forms of energy production used by cells. In this section, we discuss the next evolutionary advancement in cellular energy metabolism, oxidative phosphorylation. Foremost recall that oxidative phosphorylation does not imply the use of oxygen. Rather, the term oxidative phosphorylation is used because this process of ATP synthesis relies on redox reactions to generate an electrochemical transmembrane potential the cell can then use to do the work of ATP synthesis.

A Quick Overview of Principles Relevant to Electron Transport Chains

An ETC begins with the addition of electrons, donated from NADH, FADH2 or other reduced compounds. These electrons move through a series of electron transporters, enzymes that are embedded in a membrane, or other carriers that undergo redox reactions. The free energy transferred from these exergonic redox reactions is often coupled to the endergonic movement of protons across a membrane. Since the membrane is an effective barrier to charged species, this pumping results in an unequal accumulation of protons on either side of the membrane. This "polarizes" or "charges" the membrane, with a net positive (protons) on one side of the membrane and a negative charge on the other side of the membrane. The separation of charge creates an electrical potential. In addition, the accumulation of protons also causes a pH gradient known as a chemical potential across the membrane. Together these two gradients (electrical and chemical) are called an electro-chemical gradient.

Review: The Electron Tower

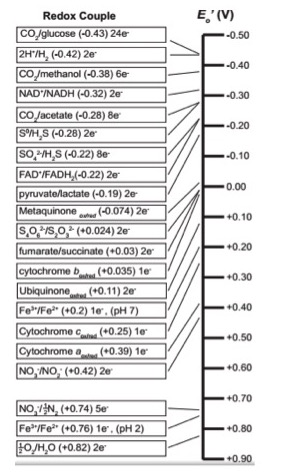

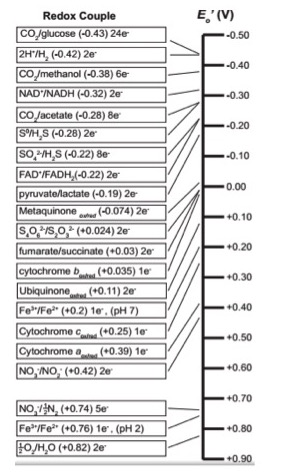

Since redox chemistry is so central to the topic we begin with a quick review of the table of reduction potential - sometimes called the "redox tower" or "electron tower". You may hear your instructors use these terms interchangeably. As we discussed in previous modules, all kinds of compounds can take part in biological redox reactions. Making sense of all of this information and ranking potential redox pairs can be confusing. We have developed a tool to rate redox half reactions based on their reduction potentials or E0' values. Whether a particular compound can act as an electron donor (reductant) or electron acceptor (oxidant) depends on what other compound it is interacting with. The redox tower ranks a variety of common compounds (their half reactions) from most negative E0', compounds that readily get rid of electrons, to the most positive E0', compounds most likely to accept electrons. The tower organizes these half reactions based on the ability of electrons to accept electrons. In addition, in many redox towers, each half reaction is written by convention with the oxidized form on the left followed by the reduced form to its right. The two forms may be either separated by a slash, for example, we write the half reaction for the reduction of NAD+ to NADH: NAD+/NADH + 2e-, or by separate columns. We show an electron tower below.

Figure 1. A common biological "redox tower"

Note

Use the redox tower above as a reference guide to orient you as to the reduction potential of the various compounds in the ETC. Redox reactions may be either exergonic or endergonic depending on the relative redox potentials of the donor and acceptor. Also remember there are many different ways of looking at this conceptually; this type of redox tower is just one way.

Note: Language shortcuts reappear

In the redox table above some entries seem to be written in unconventional ways. For instance Cytochrome cox/red. There only appears to be one form listed. Why? This is another example of language shortcuts (likely because someone was too lazy to write cytochrome twice) that can confuse - particularly to students. We could rewrite the notation above as Cytochrome cox/Cytochrome cred to show that the cytochrome c protein can exist in either and oxidized state Cytochrome cox or reduced state Cytochrome cred.

Review Redox Tower Video

For a short video on how to use the redox tower in redox problems click here. This video was made by Dr. Easlon for Bis2A students.

Using the redox tower: A tool to help understand electron transport chains

By convention, we write the tower half reactions with the oxidized form of the compound on the left and the reduced form on the right. Notice that compounds such as glucose and hydrogen gas are excellent electron donors and have very low reduction potentials E0'. Compounds, such as oxygen and nitrite, whose half reactions have relatively high positive reduction potentials (E0') make we find good electron acceptors at the opposite end of the table.

Example: Menaquinone

Let's look at menaquinoneox/red. This compound sits in the middle of the redox tower with a half-reaction E0' value of -0.074 eV. Menaquinoneox can spontaneously (ΔG<0) accept electrons from reduced forms of compounds with lower half-reaction E0'. Such transfers form menaquinonered and the oxidized form of the original electron donor. In the table above, examples of compounds that could act as electron donors to menaquinone include FADH2, an E0' value of -0.22, or NADH, with an E0' value of -0.32 eV. Remember, the reduced forms are on the right-hand side of the redox pair.

Once menaquinone has been reduced, it can now spontaneously (ΔG<0) donate electrons to any compound with a higher half-reaction E0' value. Electron acceptors include cytochrome box with an E0' value of 0.035 eV; or ubiquinoneox with an E0' of 0.11 eV. Remember that the oxidized forms lie on the left side of the half reaction.