SS1_2019_Lecture_14

- Page ID

- 23942

Mutations

Errors occurring during DNA replication are not the only way by which mutations can arise in DNA. Mutations, variations in the nucleotide sequence of a genome, can also occur because of physical damage to DNA. Such mutations may be of two types: induced or spontaneous. Induced mutations are those that result from an exposure to chemicals, UV rays, x-rays, or some other environmental agent. Spontaneous mutations occur without any exposure to any environmental agent; they are a result of spontaneous biochemical reactions taking place within the cell.

Mutations may have a wide range of effects. Some mutations are not expressed; these are known as silent mutations. Point mutations are those mutations that affect a single base pair. The most common nucleotide mutations are substitutions, in which one base is replaced by another. These can be of two types, either transitions or transversions. Transition substitution refers to a purine or pyrimidine being replaced by a base of the same kind; for example, a purine such as adenine may be replaced by the purine guanine. Transversion substitution refers to a purine being replaced by a pyrimidine, or vice versa; for example, cytosine, a pyrimidine, is replaced by adenine, a purine. Mutations can also be the result of the addition of a nucleotide, known as an insertion, or the removal of a base, also known as deletion. Sometimes a piece of DNA from one chromosome may get translocated to another chromosome or to another region of the same chromosome; this is known as translocation.

As we will visit later, when a mutation occurs in a protein coding region it may have several effects. Transition or transversion mutants may lead to no change in the protein sequence (known as silent mutations), change the amino acid sequence (known as missense mutations), or create what is known as a stop codon (known as a nonsense mutation). Insertions and deletions in protein coding sequences lead to what are known as frameshift mutations. Missense mutations that lead to conservative changes results in the substitution of similar but not identical amino acids. For example, the acidic amino acid glutamate being substituted for the acidic amino acid aspartate would be considered conservative. In general we do not expect these types of missense mutations to be as severe as a non-conservative amino acid change; such as a glutamate substituted for a valine. Drawing from our understanding of functional group chemistry we can correctly infer that this type of substitution may lead to severe functional consequences, depending upon location of the mutation.

Note: Vocabulary Watch

Note that the preceding paragraph had a lot of potentially new vocabulary - it would be a good idea to learn these terms.

Figure 1. Mutations can lead to changes in the protein sequence encoded by the DNA.

Suggested discussion

Based on your understanding of protein structure, which regions of a protein would you think are more sensitive to substitutions, even conserved amino acid substitutions? Why?

Suggested discussion

A insertion mutation that results in the insertion of three nucleotides is often less deleterious than a mutation that results in the insertion of one nucleotide. Why?

Mutations: Some nomenclature and considerations

Mutation

Etymologically speaking, the term mutation simply means a change or alteration. In genetics, a mutation is a change in the genetic material - DNA sequence - of an organism. By extension, a mutant is the organism in which a mutation has occurred. But what is the change compared to? The answer to this question, is that it depends. The comparison can be made with the direct progenitor (cell or organism) or to patterns seen in a population of the organism in question. It mostly depends on the specific context of the discussion. Since genetic studies often look at a population (or key subpopulations) of individuals we begin by describing the term "wild-type".

Wild Type vs Mutant

What do we mean by "wild type"? Since the definition can depend on context, this concept is not entirely straightforward. Here are a few examples of definitions you may run into:

Possible meanings of "wild-type"

- An organism having an appearance that is characteristic of the species in a natural breeding population (i.e. a cheetah's spots and tear-like dark streaks that extend from the eyes to the mouth).

- The form or forms of a gene most commonly occurring in nature in a given species.

- A phenotype, genotype, or gene that predominates in a natural population of organisms or strain of organisms in contrast to that of natural or laboratory mutant forms.

- The normal, as opposed to the mutant, gene or allele.

The common thread to all of the definitions listed above is based on the "norm" for a set of characteristics with respect to a specific trait compared to the overall population. In the "Pre-DNA sequencing Age" species were classified based on common phenotypes (what they looked like, where they lived, how they behaved, etc.). A "norm" was established for the species in question. For example, Crows display a common set of characteristics, they are large, black birds that live in specific regions, eat certain types of food and behave in a certain characteristic way. If we see one, we know its a crow based on these characteristics. If we saw one with a white head, we would think that either it is a different bird (not a crow) or a mutant, a crow that has some alteration from the norm or wild type.

In this class we take what is common about those varying definitions and adopt the idea that "wild type" is simply a reference standard against which we can compare members of a population.

Suggested discussion

If you were assigning wild type traits to describe a dog, what would they be? What is the difference between a mutant trait and variation of a trait in a population of dogs? Is there a wild type for a dog that we could use as a standard? How would we begin to think about this concept with respect to dogs?

Mutations are simply changes from the "wild type", reference or parental sequence for an organism. While the term "mutation" has colloquially negative connotations we must remember that change is neither inherently "bad". Indeed, mutations (changes in sequences) should not primarily be thought of as "bad" or "good", but rather simply as changes and a source of genetic and phenotypic diversity on which evolution by natural selection can occur. Natural selection ultimately determines the long-term fate of mutations. If the mutation confers a selective advantage to the organism, the mutation will be selected and may eventually become very common in the population. Conversely, if the mutation is deleterious, natural selection will ensure that the mutation will be lost from the population. If the mutation is neutral, that is it neither provides a selective advantage or disadvantage, then it may persist in the population. Different forms of a gene, including those associated with "wild type" and respective mutants, in a population are termed alleles.

Consequences of Mutations

For an individual, the consequence of mutations may mean little or it may mean life or death. Some deleterious mutations are null or knock-out mutations which result in a loss of function of the gene product. These mutations can arise by a deletion of the either the entire gene, a portion of the gene, or by a point mutation in a critical region of the gene that renders the gene product non-functional. These types of mutations are also referred to as loss-of-function mutations. Alternatively, mutations may lead to a modification of an existing function (i.e. the mutation may change the catalytic efficiency of an enzyme, a change in substrate specificity, or a change in structure). In rare cases a mutation may create a new or enhanced function for a gene product; this is often referred to as a gain-of-function mutation. Lastly, mutations may occur in non-coding regions of DNA. These mutations can have a variety of outcomes including altered regulation of gene expression, changes in replication rates or structural properties of DNA and other non-protein associated factors.

Suggested discussion

In the discussion above what types of scenarios would allow such a gain-of-function mutant the ability to out compete a wild type individual within the population? How do you think mutations relate to evolution?

Mutations and cancer

Mutations can affect either somatic cells or germ cells. Sometimes mutations occur in DNA repair genes, in effect compromising the cell's ability to fix other mutations that may arise. If, as a result of mutations in DNA repair genes, many mutations accumulate in a somatic cell, they may lead to problems such as the uncontrolled cell division observed in cancer. Cancers, including forms of pancreatic cancer, colon cancer, and colorectal cancer have been associated with mutations like these in DNA repair genes. If, by contrast, a mutation in DNA repair occurs in germ cells (sex cells), the mutation will be passed on to the next generation, as in the case of diseases like hemophilia and xeroderma pigmentosa. In the case of xeroderma pigmentoas individuals with compromised DNA repair processes become very sensitive to UV radiation. In severe cases these individuals may get severe sun burns with just minutes of exposure to the sun. Nearly half of all children with this condition develop their first skin cancers by age 10.

Consequences of errors in replication, transcription and translation

Something key to think about:

Cells have evolved a variety of ways to make sure DNA errors are both detected and corrected, rom proof reading by the various DNA-dependent DNA polymerases, to more complex repair systems. Why did so many different mechanisms evolve to repair errors in DNA? By contrast, similar proof-reading mechanisms did NOT evolve for errors in transcription or translation. Why might this be? What would be the consequences of an error in transcription? Would such an error effect the offspring? Would it be lethal to the cell? What about translation? Ask the same questions about the process of translation. What would happen if the wrong amino acid was accidentally put into the growing polypeptide during the translation of a protein? Contrast this with DNA replication.

Mutations as instruments of change

Mutations are how populations can adapt to changing environmental pressures

Mutations are randomly created in the genome of every organism, and this in turn creates genetic diversity and a plethora of different alleles per gene per organism in every population on the planet. If mutations did not occur, and chromosomes were replicated and transmitted with 100% fidelity, how would cells and organisms adapt? Whether mutations are retained by evolution in a population depends largely on whether the mutation provides selective advantage, poses some selective cost or is at the very least, not harmful. Indeed, mutations that appear neutral may persist in the population for many generations and only be meaningful when a population is challenged with a new environmental challenge. At this point the apparently previously neutral mutations may provide a selective advantage.

Example: Antibiotic resistance

The bacterium E. coli is sensitive to an antibiotic called streptomycin, which inhibits protein synthesis by binding to the ribosome. The ribosomal protein L12 can be mutated such that streptomycin no longer binds to the ribosome and inhibits protein synthesis. Wild type and L12 mutants grow equally well and the mutation appears to be neutral in the absence of the antibiotic. In the presence of the antibiotic wild type cells die and L12 mutants survive. This example shows how genetic diversity is important for the population to survive. If mutations did not randomly occur, when the population is challenged by an environmental event, such as the exposure to streptomycin, the entire population would die. For most populations this becomes a numbers game. If the mutation rate is 10-6 then a population of 107 cells would have 10 mutants; a population of 108 would have 100 mutants, etc.

Uncorrected errors in DNA replication lead to mutation. In this example, an uncorrected error was passed onto a bacterial daughter cell. This error is in a gene that encodes for part of the ribosome. The mutation results in a different final 3D structure of the ribosome protein. While the wildtype ribosome can bind to streptomycin (an antibiotic that will kill the bacterial cell by inhibiting the ribosome function) the mutant ribosome cannot bind to streptomycin. This bacteria is now resistant to streptomycin.

Source: Bis2A Team original image

Suggested discussion

Based on our example, if you were to grow up a culture of E. coli to population density of 109 cells/ml; would you expect the entire population to be identical? How many mutants would you expect to see in 1 ml of culture?

An example: Lactate dehydrogenase

Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH), the enzyme that catalyzes the reduction of pyruvate into lactic acid in fermentation, while virtually every organism has this activity, the corresponding enzyme and therefore gene differs immensely between humans and bacteria. The proteins are clearly related, they perform the same basic function but have a variety of differences, from substrate binding affinities and reaction rates to optimal salt and pH requirements. Each of these attributes have been evolutionarily tuned for each specific organism through multiple rounds of mutation and selection.

Suggested discussion

We can use comparative DNA sequence analysis to generate hypotheses about the evolutionary relationships between three or more organisms. One way to accomplish this is to compare the DNA or protein sequences of proteins found in each of the organisms we wish to compare. Let us, for example, imagine that we were to compare the sequences of LDH from three different organisms, Organism A, Organism B and Organism C. If we compare the LDH protein sequence from Organism A to that from Organism B we find a single amino acid difference. If we now look at Organism C, we find 2 amino acid differences between its LDH protein and the one in Organism A and one amino acid difference when the enzyme from Organism C is compared to the one in Organism B. Both organisms B and C share a common change compared to organism A.

Schematic depicting the primary structures of LDH proteins from Organism A, Organism B, and Organism C. The letters in the center of the proteins line diagram represent amino acids at a unique position and the proposed differences in each sequence. The N and C termini are also noted H2N and COOH, respectively.

Attribution: Marc T. Facciotti (original work)

Question: Is Organism C more closely related to Organism A or B? The simplest explanation is that Organism A is the earliest form, a mutation occurred giving rise to Organism B. Over time a second mutation arose in the B lineage to give rise to the enzyme found in Organism C. This is the simplest explanation, however we can not rule out other possibilities. Can you think of other ways the different forms of the LDH enzyme arose these three organisms?

Real-life Application:

As we have seen in the "Mutations and Mutants" module, changing even one nucleotide can have major effects on the translated product. Read more about an undergraduate's work on point mutations and GMOs here.

GLOSSARY

- induced mutation:

-

mutation that results from exposure to chemicals or environmental agents

- mutation:

-

variation in the nucleotide sequence of a genome

- mismatch repair:

-

type of repair mechanism in which mismatched bases are removed after replication

- nucleotide excision repair:

-

type of DNA repair mechanism in which the wrong base, along with a few nucleotides upstream or downstream, are removed

- proofreading:

-

function of DNA pol in which it reads the newly added base before adding the next one

- point mutation:

-

mutation that affects a single base

- silent mutation:

-

mutation that is not expressed

- spontaneous mutation:

-

mutation that takes place in the cells as a result of chemical reactions taking place naturally without exposure to any external agent

- transition substitution:

-

when a purine is replaced with a purine or a pyrimidine is replaced with another pyrimidine

- transversion substitution:

-

when a purine is replaced by a pyrimidine or a pyrimidine is replaced by a purine

Introduction to cell division

An evolutionary goal of all living systems is to reproduce. Since the basic unit of life is a cell, and we know - thanks at least in part to Francesco Reid - that life begets new life - this means that there must be a process by which to create new cells from parental cells. We also know intuitively that multicellular organisms must somehow increase their number of cells during their growth by creating copies of existing cells. The process by which one cell creates one or more new cells, for both single and multi-celled organisms, requires a parental cell to divide and is called cell division.

The cell must replicate its DNA so that at least two cells have a functional copy after cell division is complete - we have discussed this process already. The cell must make sufficient copies of the rest of the cellular content so that daughter cells are viable or it must find a way to ensure that the copied DNA (even without a full replica of cellular content) is viable. The cell must divide the replicated cell content and DNA between at least two independently bounded compartments. To ensure success, the process must be happen in an evolutionarily competitive time and be accomplished with an evolutionary selection-friendly amount of biochemical resources.

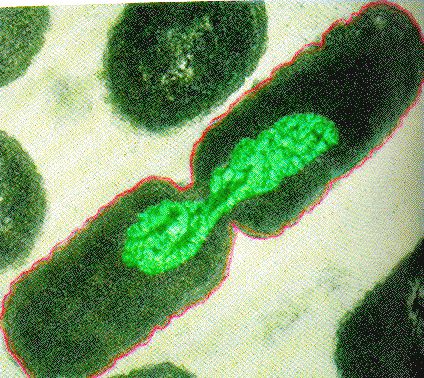

From the standpoint of the Design Challenge framework we can stipulate that the big problem of cell division is to make a copy of a cell. If a condition for success requires that the daughter cells be viable then a number of subproblems can be defined:These images show the steps of binary fission in prokaryotes. (credit: modification of work by “Mcstrother”/Wikimedia Commons)

Control of these processes

Not surprisingly, the process of binary fission is strictly controlled in most bacteria and archaea. Somewhat surprisingly, however, while some key molecular players are know, much remains to be discovered and understood about how decisions are made to coordinate the activities.

While it is not a strict requirement that this process happen in a coordinated manner, Nature has selected for systems in which all of the steps in the process happen in a highly coordinated way. This helps cells meet requirement number 4 in the list above. The coordinated process and the mechanisms of control are generally referred to as the cell cycle. This term can be used to describe the coordinate process used by any cell that is undergoing cell division. When we observe Nature we find that it has evolved two major modes of reproduction: sexual and asexual. Within each of these modes of reproduction we find several major modes of cell division that occur frequently across all domains of life. We consider three of these modes: binary fission (used primarily by single celled bacteria and archaea), mitosis (used often by eukaryotes in processes of cell division NOT associated with sexual reproduction) and meiosis (a process of cell division tightly linked to sexual reproduction). We discuss these processes in the sections that follow.

Figure. First-year UC Davis students enrolled in a hands-on first-year seminar course examine an agar plate of on which they have "painted" designs with an engineered strain of Escherschia coli. The designs only become apparent after the bacteria multiply through the process of binary fission. Opportunities for getting involved in hands-on research abound on the UC Davis campus - make sure to set time aside to get involved before you graduate. (Photo: by undergraduate student Daniel Oberbauer - 2017)

Cell division in the bacteria and archaea

Bacteria and Archaea

Like all other life forms, bacteria and archaea have one key evolutionary driver: to make more of themselves. Typically, bacterial and archaeal cells grow, duplicate all major cellular constituents, like DNA, ribosomes, etc., distribute this content and then divide into two nearly identical daughter cells. This process is called binary fission and is shown mid-process in the figure below. While some bacterial species are known to use several alternative reproductive strategies including making multiple offspring or budding - and all alternative mechanisms still meet the requirements for cell division stipulated above - binary fission is the most commonly laboratory-observed mechanisms for cell division the bacteria and archaea so we limit our discussion to this mechanisms alone.

(Aside: Those who want to read more about alternatives to binary fission in bacteria should check this link out.)

Binary Fission in bacteria starts with DNA replication at the replication origin attached to the cell wall, near the midpoint of the cell. New replication forks can form before the first cell division ends; this phenomenon allows an extremely rapid rate of reproduction. Source: http://biology.kenyon.edu/courses/bi...01/week01.html

Binary Fission

The process of binary fission is the most commonly observed mechanism for cell division in bacteria and archaea (at least the culturable ones studied in the laboratory). The following is a description of a process that happens in some rod-shaped bacteria:

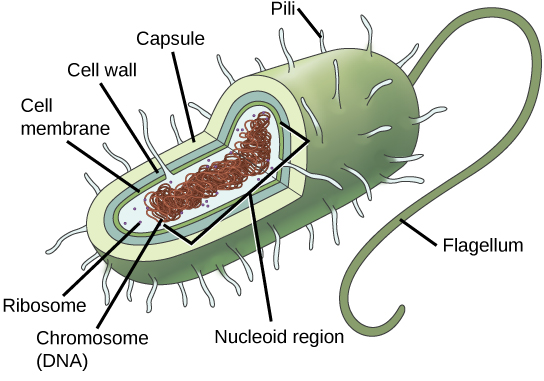

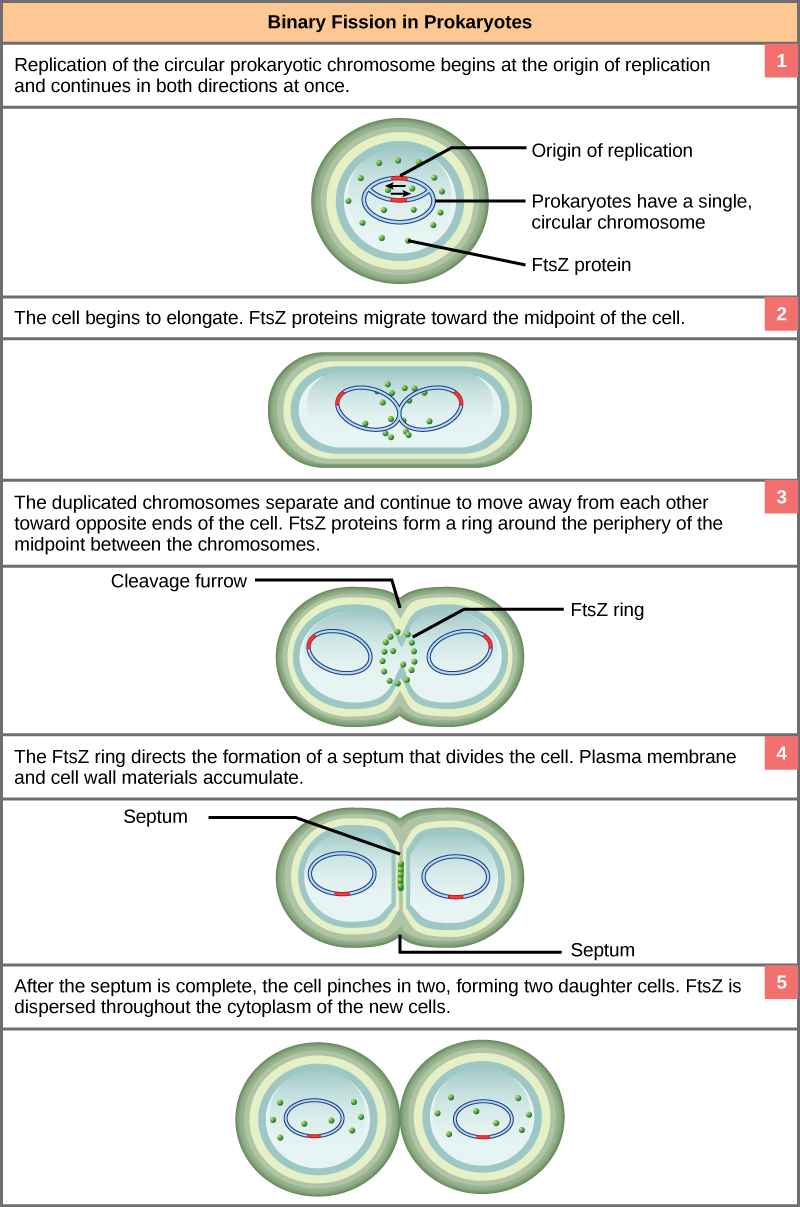

Since we must consider the replication of DNA one structural feature of relevance to DNA replication in the bacteria and archaea is that their genetic material is not enclosed in a nucleus, but instead occupies a specific location, the nucleoid, within the cell. Moreover, the DNA of the nucleoid is associated with numerous proteins that aid in compacting the DNA into a smaller, organized structure. Another organizational feature to note is that the bacterial chromosome is typically attached to the plasma membrane at about the midpoint of the cell. The starting point of replication, the origin, is close to this attachment site. Recall also that replication of the DNA is bidirectional, with replication forks moving away from the origin on both strands of the loop simultaneously. Due to the structural arrangement of the DNA at the midpoint this means that as the new double strands are formed, each origin point moves away from the cell wall attachment toward the opposite ends of the cell.

This process of DNA replication is typically occurring at the same time as a growth in the physical dimensions of the cell. Therefore, as the cell elongates, the growing membrane aids in the transport of the chromosomes towards the two opposite poles of the cells. After the chromosomes have cleared the midpoint of the elongated cell, cytoplasmic separation begins.

The formation of a ring composed of repeating units of a protein called FtsZ (a cytoskeletal protein) directs the formation of a partition between the two new nucleoids. Formation of the FtsZ ring triggers the accumulation of other proteins that work together to recruit new membrane and cell wall materials to the site. Gradually, a septum is formed between the nucleoids, extending from the periphery toward the center of the cell. When the new cell walls are in place, the daughter cells separate.

Prokaryotes, including bacteria and archaea, have a single, circular chromosome located in a central region called the nucleoid.

Possible discussion

How does attaching the replicating chromosome to the cell membrane aid in dividing the two chromosomes after replication is complete?

Eukaryotic Cell Cycle and Mitosis

The cell cycle is an orderly sequence of events used by biological systems to coordinate cell division. In eukaryotes, asexual cell division proceeds via a cell cycle that includes multiple spatially and temporally coordinated events. These include a long preparatory period, called interphase and a mitotic phase called M phase. Interphase is often further divided into distinguishable subphases called G1, S, and G2 phases. Mitosis is the stage in which replicated DNA is distributed to daughter cells and is itself often subdivided into five distinguishable stages: prophase, prometaphase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase. Mitosis is often accompanied by a process called cytokinesis, during which the cytoplasmic components of the daughter cells are separated either by an actin ring (animal cells) or by cell plate formation (plant cells). The passage through these phases are controlled by checkpoints. There are three major checkpoints in the cell cycle: one near the end of G1, a second at the G2–M transition, and the third during metaphase. These regulatory checks serve to ensure that the processes required to successfully move on to the next phase of the cell cycle have been fully completed and that sufficient resources exist to move on to the next phase of cell division.

Cell Cycle

In asexually reproducing eukaryotic cells, one “turn” of the cell cycle consists of two general phases: interphase, followed by mitosis and cytokinesis. Interphase is the period of the cell cycle during which the cell may either be living and not dividing or in which it is preparing itself to divide. Most of the cells in a fully-developed multicellular organisms are typically found in interphase. Mitosis is the the point in the cell cycle associated with division or distribution of replicated genetic material to two daughter cells. During mitosis the cell nucleus breaks down and two new, fully functional, nuclei are formed. Cytokinesis is the process that divides the cytoplasm into two distinctive cells.

Interphase

G1 Phase

The first stage of interphase is called the G1 phase, or first gap, because little change is visible. However, during the G1 stage, the cell is quite active at the biochemical level. The cell is accumulating the building blocks of chromosomal DNA and the associated proteins, as well as accumulating enough energy reserves to complete the task of replicating each chromosome in the nucleus.

A cell moves through a series of phases in an orderly manner. During interphase, G1 involves cell growth and protein synthesis, the S phase involves DNA replication and the replication of the centrosome, and G2 involves further growth and protein synthesis. The mitotic phase follows interphase. Mitosis is nuclear division during which duplicated chromosomes are segregated and distributed into daughter nuclei. Usually the cell will divide after mitosis in a process called cytokinesis in which the cytoplasm is divided and two daughter cells are formed.

S Phase

Throughout interphase, nuclear DNA remains in a semi-condensed chromatin configuration. In S phase (synthesis phase), DNA replication results in the formation of two identical copies of each chromosome—sister chromatids—that are firmly attached at the centromere region. At the end of this stage, each chromosome has been replicated.

In cells using the organelles called centrosomes, these structures are often duplicated during S phase. Centrosomes consists of a pair of rod-like centrioles composed of tubulin and other proteins that sit at right angles to one another other. The two resulting centrosomes will give rise to the mitotic spindle, the apparatus that orchestrates the movement of chromosomes later during mitosis.

G2 Phase

During the G2 phase, or second gap, the cell replenishes its energy stores and synthesizes the proteins necessary for chromosome manipulation. Some cell organelles are duplicated, and the cytoskeleton is dismantled to provide resources for the mitotic spindle. There may be additional cell growth during G2. The final preparations for the mitotic phase must be completed before the cell is able to enter the first stage of mitosis.

G0 Phase

Not all cells adhere to the classic cell-cycle pattern in which a newly formed daughter cell immediately enters interphase, closely followed by the mitotic phase. Cells in the G0 phase are not actively preparing to divide. The cell is in a quiescent (inactive) stage, having exited the cell cycle. Some cells enter G0 temporarily until an external signal triggers the onset of G1. Other cells that never or rarely divide, such as mature cardiac muscle and nerve cells, remain in G0 permanently

A Quick Aside: Structure of Chromosomes During the Cell Cycle

If the DNA from all 46 chromosomes in a human cell nucleus was laid out end to end, it would measure approximately two meters; however, its diameter would be only 2 nm. Considering that the size of a typical human cell is about 10 µm (100,000 cells lined up to equal one meter), DNA must be tightly packaged to fit in the cell’s nucleus. At the same time, it must also be readily accessible for the genes to be expressed. During some stages of the cell cycle, the long strands of DNA are condensed into compact chromosomes. There are a number of ways that chromosomes are compacted.

Suggested discussion

When should we expect to see highly condensed DNA in the cell (which phases of the cell cycle)? When would the DNA remain un-compacted (during which phases of the cell cycle)?

Double-stranded DNA wraps around histone proteins to form nucleosomes that have the appearance of “beads on a string.” The nucleosomes are coiled into a 30-nm chromatin fiber. When a cell undergoes mitosis, the chromosomes condense even further.

Mitosis and Cytokinesis

During the mitotic phase, a cell undergoes two major processes. First, it completes mitosis, during which the contents of the nucleus are equitably pulled apart and distributed between its two halves. Cytokinesis then occurs, dividing the cytoplasm and cell body into two new cells.

Note

The major phases of Mitosis are visually distinct from one another and were originally characterized by what could be seen by viewing dividing cells under a microscope. Some instructors may ask you be able to distinguish each phase be looking at images of cells or more commonly by inspection of cartoon depiction of mitosis. If your instructor is not explicit about this point remember to ask whether this will be expected of you.

The stages of cell division oversee the separation of identical genetic material into two new nuclei, followed by the division of the cytoplasm. Animal cell mitosis is divided into five stages—prophase, prometaphase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase—visualized here by light microscopy with fluorescence. Mitosis is usually accompanied by cytokinesis, shown here by a transmission electron microscope. (credit "diagrams": modification of work by Mariana Ruiz Villareal; credit "mitosis micrographs": modification of work by Roy van Heesbeen; credit "cytokinesis micrograph": modification of work by the Wadsworth Center, NY State Department of Health; donated to the Wikimedia foundation; scale-bar data from Matt Russell)

Prophase

Prophase is the first phase of mitosis, during which the loosely packed chromatin coils and condenses into visible chromosomes. During prophase, each chromosome becomes visible with its identical partner (sister chromatid) attached, forming the familiar X-shape of sister chromatids. The nucleolus disappears early during this phase, and the nuclear envelope also disintegrates.

A major occurrence during prophase concerns a very important structure that contains the origin site for microtubule growth. Cellular structures called centrioles that serve as origin points from which microtubules extend. These tiny structures also play a very important role during mitosis. A centrosome is a pair of centrioles together. The cell contains two centrosomes side-by-side, which begin to move apart during prophase. As the centrosomes migrate to two different sides of the cell, microtubules begin to extend from each like long fingers from two hands extending toward each other. The mitotic spindle is the structure composed of the centrosomes and their emerging microtubules.

Near the end of prophase there is an invasion of the nuclear area by microtubules from the mitotic spindle. The nuclear membrane has disintegrated, and the microtubules attach themselves to the centromeres that adjoin pairs of sister chromatids. The kinetochore is a protein structure on the centromere that is the point of attachment between the mitotic spindle and the sister chromatids. This stage is referred to as late prophase or “prometaphase” to indicate the transition between prophase and metaphase.

Metaphase

Metaphase is the second stage of mitosis. During this stage, the sister chromatids, with their attached microtubules, line up along a linear plane in the middle of the cell. A metaphase plate forms between the centrosomes that are now located at either end of the cell. The metaphase plate is the name for the plane through the center of the spindle on which the sister chromatids are positioned. The microtubules are now poised to pull apart the sister chromatids and bring one from each pair to each side of the cell.

Anaphase

Anaphase is the third stage of mitosis. Anaphase takes place over a few minutes, when the pairs of sister chromatids are separated from one another, forming individual chromosomes once again. These chromosomes are pulled to opposite ends of the cell by their kinetochores, as the microtubules shorten. Each end of the cell receives one partner from each pair of sister chromatids, ensuring that the two new daughter cells will contain identical genetic material.

Telophase

Telophase is the final stage of mitosis. Telophase is characterized by the formation of two new daughter nuclei at either end of the dividing cell. These newly formed nuclei surround the genetic material, which uncoils such that the chromosomes return to loosely packed chromatin. Nucleoli also reappear within the new nuclei, and the mitotic spindle breaks apart, each new cell receiving its own complement of DNA, organelles, membranes, and centrioles. At this point, the cell is already beginning to split in half as cytokinesis begins.

Cytokinesis

Cytokinesis is the second part of the mitotic phase during which cell division is completed by the physical separation of the cytoplasmic components into two daughter cells. Although the stages of mitosis are similar for most eukaryotes, the process of cytokinesis is quite different for eukaryotes that have cell walls, such as plant cells.

In cells such as animal cells that lack cell walls, cytokinesis begins following the onset of anaphase. A contractile ring composed of actin filaments forms just inside the plasma membrane at the former metaphase plate. The actin filaments pull the equator of the cell inward, forming a fissure. This fissure, or “crack,” is called the cleavage furrow. The furrow deepens as the actin ring contracts, and eventually the membrane and cell are cleaved in two (see the figure below).

In plant cells, a cleavage furrow is not possible because of the rigid cell walls surrounding the plasma membrane. A new cell wall must form between the daughter cells. During interphase, the Golgi apparatus accumulates enzymes, structural proteins, and glucose molecules prior to breaking up into vesicles and dispersing throughout the dividing cell. During telophase, these Golgi vesicles move on microtubules to collect at the metaphase plate. There, the vesicles fuse from the center toward the cell walls; this structure is called a cell plate. As more vesicles fuse, the cell plate enlarges until it merges with the cell wall at the periphery of the cell. Enzymes use the glucose that has accumulated between the membrane layers to build a new cell wall of cellulose. The Golgi membranes become the plasma membrane on either side of the new cell wall (see panel b in the figure below).

In part (a), a cleavage furrow forms at the former metaphase plate in the animal cell. The plasma membrane is drawn in by a ring of actin fibers contracting just inside the membrane. The cleavage furrow deepens until the cells are pinched in two. In part (b), Golgi vesicles coalesce at the former metaphase plate in a plant cell. The vesicles fuse and form the cell plate. The cell plate grows from the center toward the cell walls. New cell walls are made from the vesicle contents.

Cell Cycle Check Points

It is essential that daughter cells be nearly exact duplicates of the parent cell. Mistakes in the duplication or distribution of the chromosomes lead to mutations that may be passed forward to every new cell produced from the abnormal cell. To prevent a compromised cell from continuing to divide, there are internal control mechanisms that operate at three main cell cycle checkpoints at which the cell cycle can be stopped until conditions are favorable. These checkpoints occur near the end of G1, at the G2–M transition, and during metaphase (see figure below).

The cell cycle is controlled at three checkpoints. Integrity of the DNA is assessed at the G1 checkpoint. Proper chromosome duplication is assessed at the G2 checkpoint. Attachment of each kinetochore to a spindle fiber is assessed at the M checkpoint.

G1 Checkpoint

The G1 checkpoint determines whether all conditions are favorable for cell division to proceed into S phase where DNA replication occurs. The G1 checkpoint, also called the restriction point, is the point at which the cell irreversibly commits to the cell-division process. In addition to adequate reserves and cell size, there is a check for damage to the genomic DNA at the G1 checkpoint. A cell that does not meet all the requirements will not be released into the S phase.

G2 Checkpoint

The G2 checkpoint bars the entry to the mitotic phase if certain conditions are not met. As in the G1 checkpoint, cell size and protein reserves are assessed. However, the most important role of the G2 checkpoint is to ensure that all of the chromosomes have been replicated and that the replicated DNA is not damaged.

M Checkpoint

The M checkpoint occurs near the end of the metaphase stage of mitosis. The M checkpoint is also known as the spindle checkpoint because it determines if all the sister chromatids are correctly attached to the spindle microtubules. Because the separation of the sister chromatids during anaphase is an irreversible step, the cycle will not proceed until the kinetochores of each pair of sister chromatids are firmly anchored to spindle fibers arising from opposite poles of the cell.

Note

Watch what occurs at the G1, G2, and M checkpoints by visiting this animation of the cell cycle.

When the Cell Cycle gets out of Control

Most people understand that cancer or tumors are caused by abnormal cells that multiply continuously. If the abnormal cells continue to divide unstopped, they can damage the tissues around them, spread to other parts of the body, and eventually result in death. In healthy cells, the tight regulation mechanisms of the cell cycle prevent this from happening, while failures of cell cycle control can cause unwanted and excessive cell division. Failures of control may be caused by inherited genetic abnormalities that compromise the function of certain “stop” and “go” signals. Environmental insult that damages DNA can also cause dysfunction in those signals. Often, a combination of both genetic predisposition and environmental factors lead to cancer.

The process of a cell escaping its normal control system and becoming cancerous may actually happen throughout the body quite frequently. Fortunately, certain cells of the immune system are capable of recognizing cells that have become cancerous and destroying them. However, in certain cases the cancerous cells remain undetected and continue to proliferate. If the resulting tumor does not pose a threat to surrounding tissues, it is said to be benign and can usually be easily removed. If capable of damage, the tumor is considered malignant and the patient is diagnosed with cancer.

Homeostatic Imbalances: Cancer Arises from Homeostatic Imbalances

Cancer is an extremely complex condition, capable of arising from a wide variety of genetic and environmental causes. Typically, mutations or aberrations in a cell’s DNA that compromise normal cell cycle control systems lead to cancerous tumors. Cell cycle control is an example of a homeostatic mechanism that maintains proper cell function and health. While progressing through the phases of the cell cycle, a large variety of intracellular molecules provide stop and go signals to regulate movement forward to the next phase. These signals are maintained in an intricate balance so that the cell only proceeds to the next phase when it is ready. This homeostatic control of the cell cycle can be thought of like a car’s cruise control. Cruise control will continually apply just the right amount of acceleration to maintain a desired speed, unless the driver hits the brakes, in which case the car will slow down. Similarly, the cell includes molecular messengers, such as cyclins, that push the cell forward in its cycle.

In addition to cyclins, a class of proteins that are encoded by genes called proto-oncogenes provide important signals that regulate the cell cycle and move it forward. Examples of proto-oncogene products include cell-surface receptors for growth factors, or cell-signaling molecules, two classes of molecules that can promote DNA replication and cell division. In contrast, a second class of genes known as tumor suppressor genes sends stop signals during a cell cycle. For example, certain protein products of tumor suppressor genes signal potential problems with the DNA and thus stop the cell from dividing, while other proteins signal the cell to die if it is damaged beyond repair. Some tumor suppressor proteins also signal a sufficient surrounding cellular density, which indicates that the cell need not presently divide. The latter function is uniquely important in preventing tumor growth: normal cells exhibit a phenomenon called “contact inhibition;” thus, extensive cellular contact with neighboring cells causes a signal that stops further cell division.

These two contrasting classes of genes, proto-oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes, are like the accelerator and brake pedal of the cell’s own “cruise control system,” respectively. Under normal conditions, these stop and go signals are maintained in a homeostatic balance. Generally speaking, there are two ways that the cell’s cruise control can lose control: a malfunctioning (overactive) accelerator, or a malfunctioning (underactive) brake. When compromised through a mutation, or otherwise altered, proto-oncogenes can be converted to oncogenes, which produce oncoproteins that push a cell forward in its cycle and stimulate cell division even when it is undesirable to do so. For example, a cell that should be programmed to self-destruct (a process called apoptosis) due to extensive DNA damage might instead be triggered to proliferate by an oncoprotein. On the other hand, a dysfunctional tumor suppressor gene may fail to provide the cell with a necessary stop signal, also resulting in unwanted cell division and proliferation.

A delicate homeostatic balance between the many proto-oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes delicately controls the cell cycle and ensures that only healthy cells replicate. Therefore, a disruption of this homeostatic balance can cause aberrant cell division and cancerous growths.