1.3.3: Instruments of Microscopy

- Page ID

- 42468

Section Learning Objectives

- Identify and describe the parts of a brightfield microscope

- Calculate total magnification for a compound microscope

- Describe the distinguishing features and typical uses for various types of light microscopes and electron microscopes

Related Chapter Learning Outcomes:

- Determine the appropriate type of microscopy to use in a situation (bright field, fluorescence, TEM, SEM)

- Distinguish between images produced by various forms of microscopy (bright field, fluorescence, TEM, SEM)

- Provide a rough timeline of the development of the forms of microscopy presented (bright field, fluorescence, TEM, SEM)

The early pioneers of microscopy opened a window into the invisible world of microorganisms. But microscopy continued to advance in the centuries that followed. In 1830, Joseph Jackson Lister created an essentially modern light microscope. The 20th century saw the development of microscopes that leveraged nonvisible light, such as fluorescence microscopy, which uses an ultraviolet light source, and electron microscopy, which uses short-wavelength electron beams. These advances led to major improvements in magnification, resolution, and contrast. By comparison, the relatively rudimentary microscopes of van Leeuwenhoek and his contemporaries were far less powerful than even the most basic microscopes in use today. In this section, we will survey the broad range of modern microscopic technology and common applications for each type of microscope.

Magnification, Resolution, and Contrast

Microscopes magnify images and use the properties of light to create useful images of small objects. Magnification is defined as the ability of a lens to enlarge the image of an object when compared to the real object. For example, a magnification of 10⨯ means that the image appears 10 times the size of the object as viewed with the naked eye.

Greater magnification typically improves our ability to see details of small objects, but magnification alone is not sufficient to make the most useful images. It is often useful to enhance the resolution of objects: the ability to tell that two separate points or objects are separate. A low-resolution image appears fuzzy, whereas a high-resolution image appears sharp. Two factors affect resolution. The first is wavelength. Shorter wavelengths are able to resolve smaller objects; thus, an electron microscope has a much higher resolution than a light microscope, since it uses an electron beam with a very short wavelength, as opposed to the long-wavelength visible light used by a light microscope. The second factor that affects resolution is numerical aperture, which is a measure of a lens’s ability to gather light. The higher the numerical aperture, the better the resolution.

Even when a microscope has high resolution, it can be difficult to distinguish small structures in many specimens because microorganisms are relatively transparent. It is often necessary to increase contrast to detect different structures in a specimen. Various types of microscopes use different features of light or electrons to increase contrast—visible differences between the parts of a specimen. Additionally, dyes that bind to some structures but not others can be used to improve the contrast between images of relatively transparent objects (see Staining Microscopic Specimens).

Light Microscopy

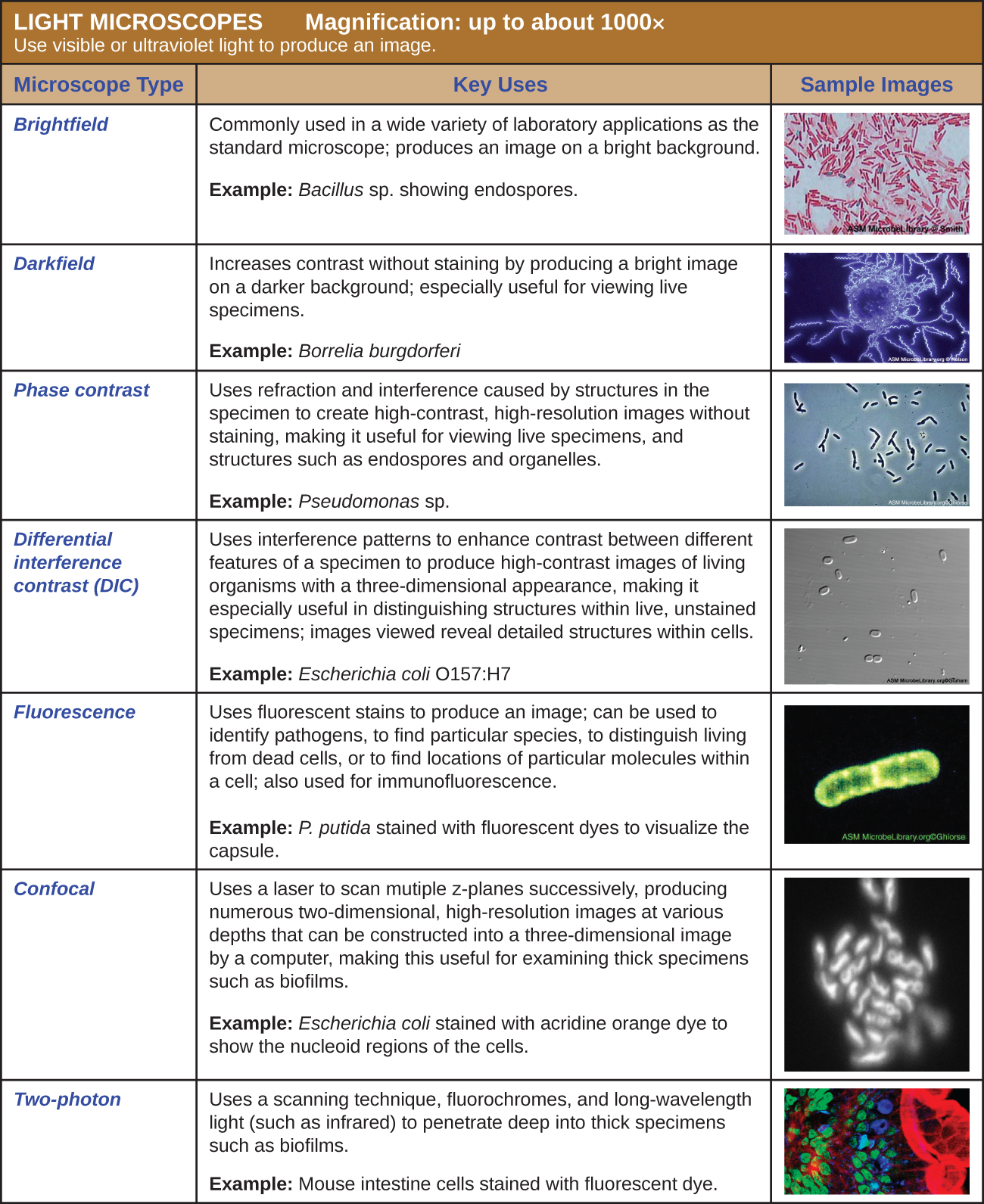

Many types of microscopes fall under the category of light microscopes, which use light to visualize images. Examples of light microscopes include brightfield microscopes, darkfield microscopes, phase-contrast microscopes, differential interference contrast microscopes, fluorescence microscopes, confocal scanning laser microscopes, and two-photon microscopes. These various types of light microscopes can be used to complement each other in diagnostics and research.

Brightfield Microscopes

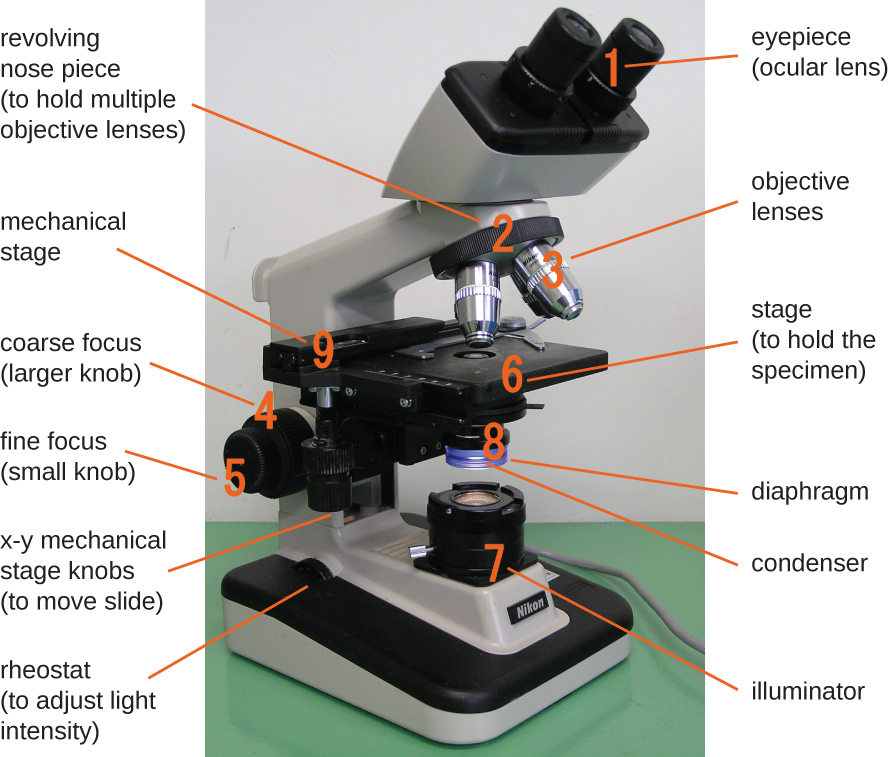

The brightfield microscope, perhaps the most commonly used type of microscope, is a compound microscope with two or more lenses that produce a dark image on a bright background. Some brightfield microscopes are monocular (having a single eyepiece), though most newer brightfield microscopes are binocular (having two eyepieces), like the one shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\); in either case, each eyepiece contains a lens called an ocular lens. The ocular lenses typically magnify images 10 times (10⨯). At the other end of the body tube are a set of objective lenses on a rotating nosepiece. The magnification of these objective lenses typically ranges from 4⨯ to 100⨯, with the magnification for each lens designated on the metal casing of the lens. The ocular and objective lenses work together to create a magnified image. The total magnification is the product of the ocular magnification times the objective magnification:

\[\text{ocular magnification} \times \text{objective magnificationocular magnification}\; \times\; \text{objective magnification} \nonumber\]

For example, if a \(40 \times\) objective lens is selected and the ocular lens is \(10\times\), the total magnification would be

\[(40×)(10×)=400× \nonumber\]

Components of a typical brightfield microscope.

The item being viewed is called a specimen. The specimen is placed on a glass slide, which is then clipped into place on the stage(a platform) of the microscope. Once the slide is secured, the specimen on the slide is positioned over the light using the x-y mechanical stage knobs. These knobs move the slide on the surface of the stage, but do not raise or lower the stage. Once the specimen is centered over the light, the stage position can be raised or lowered to focus the image. The coarse focusing knob is used for large-scale movements with 4⨯ and 10⨯ objective lenses; the fine focusing knob is used for small-scale movements, especially with 40⨯ or 100⨯ objective lenses.

When images are magnified, they become dimmer because there is less light per unit area of image. Highly magnified images produced by microscopes, therefore, require intense lighting. In a brightfield microscope, this light is provided by an illuminator, which is typically a high-intensity bulb below the stage. Light from the illuminator passes up through condenser lens (located below the stage), which focuses all of the light rays on the specimen to maximize illumination. The position of the condenser can be optimized using the attached condenser focus knob; once the optimal distance is established, the condenser should not be moved to adjust the brightness. If less-than-maximal light levels are needed, the amount of light striking the specimen can be easily adjusted by opening or closing a diaphragm between the condenser and the specimen. In some cases, brightness can also be adjusted using the rheostat, a dimmer switch that controls the intensity of the illuminator.

A brightfield microscope creates an image by directing light from the illuminator at the specimen; this light is differentially transmitted, absorbed, reflected, or refracted by different structures. Different colors can behave differently as they interact withchromophores (pigments that absorb and reflect particular wavelengths of light) in parts of the specimen. Often, chromophores are artificially added to the specimen using stains, which serve to increase contrast and resolution. In general, structures in the specimen will appear darker, to various extents, than the bright background, creating maximally sharp images at magnifications up to about 1000⨯. Further magnification would create a larger image, but without increased resolution. This allows us to see objects as small as bacteria, which are visible at about 400⨯ or so, but not smaller objects such as viruses.

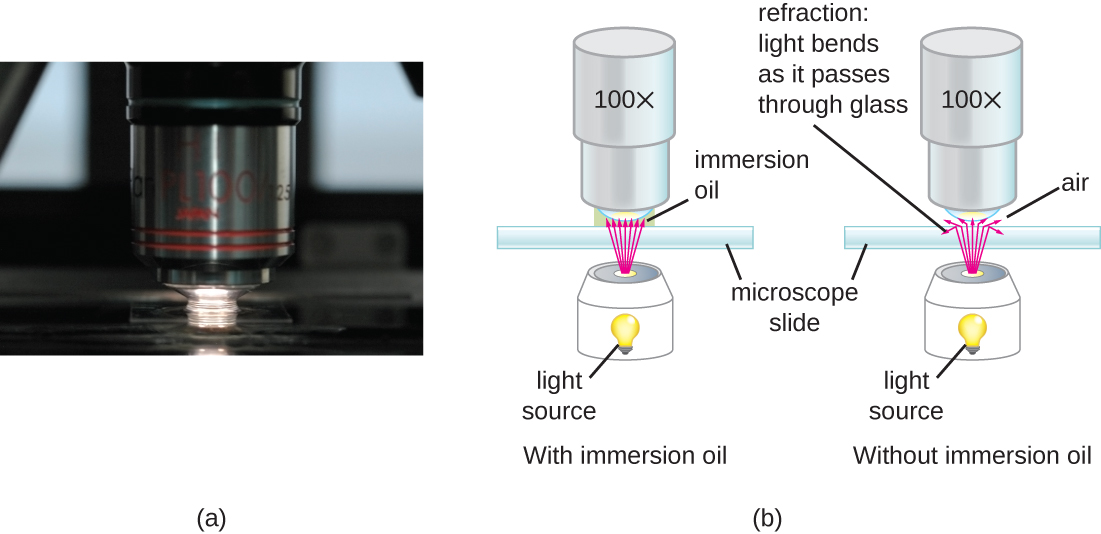

At very high magnifications, resolution may be compromised when light passes through the small amount of air between the specimen and the lens. This is due to the large difference between the refractive indices of air and glass; the air scatters the light rays before they can be focused by the lens. To solve this problem, a drop of oil can be used to fill the space between the specimen and an oil immersion lens, a special lens designed to be used with immersion oils. Since the oil has a refractive index very similar to that of glass, it increases the maximum angle at which light leaving the specimen can strike the lens. This increases the light collected and, thus, the resolution of the image (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)). A variety of oils can be used for different types of light.

MICROSCOPE MAINTENANCE: BEST PRACTICES

Even a very powerful microscope cannot deliver high-resolution images if it is not properly cleaned and maintained. Since lenses are carefully designed and manufactured to refract light with a high degree of precision, even a slightly dirty or scratched lens will refract light in unintended ways, degrading the image of the specimen. In addition, microscopes are rather delicate instruments, and great care must be taken to avoid damaging parts and surfaces. Among other things, proper care of a microscope includes the following:

- cleaning the lenses with lens paper

- not allowing lenses to contact the slide (e.g., by rapidly changing the focus)

- protecting the bulb (if there is one) from breakage

- not pushing an objective into a slide

- not using the coarse focusing knob when using the 40⨯ or greater objective lenses

- only using immersion oil with a specialized oil objective, usually the 100⨯ objective

- cleaning oil from immersion lenses after using the microscope

- cleaning any oil accidentally transferred from other lenses

- covering the microscope or placing it in a cabinet when not in use

Fluorescence Microscopes

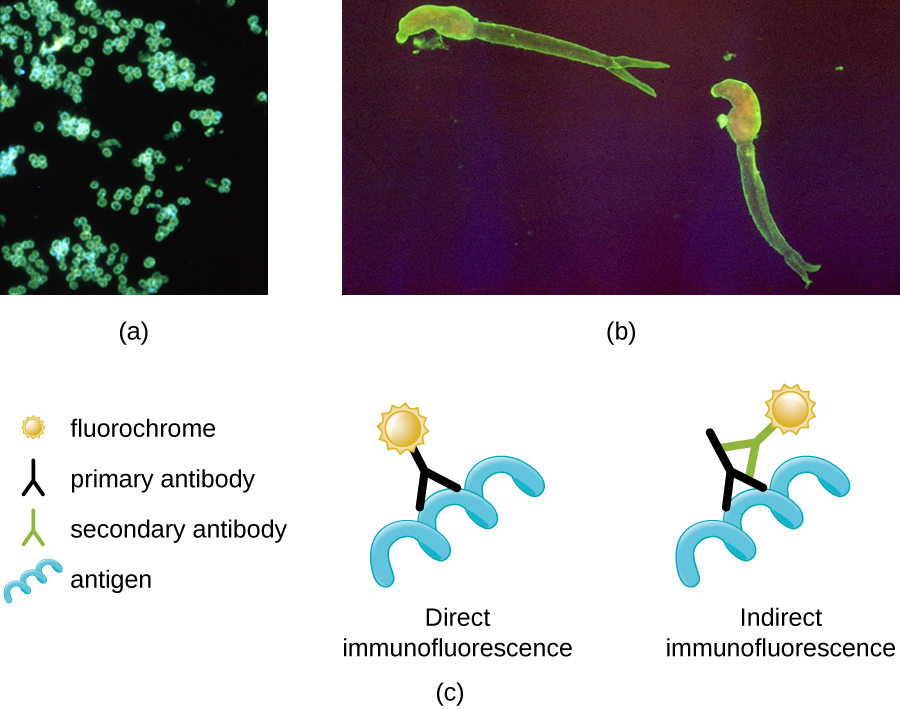

A fluorescence microscope uses fluorescent chromophores called fluorochromes, which are capable of absorbing energy from a light source and then emitting this energy as visible light. Fluorochromes include naturally fluorescent substances (such as chlorophylls) as well as fluorescent stains that are added to the specimen to create contrast. Dyes such as Texas red and FITC are examples of fluorochromes. Other examples include the nucleic acid dyes 4’,6’-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and acridine orange.

The microscope transmits an excitation light, generally a form of EMR with a short wavelength, such as ultraviolet or blue light, toward the specimen; the chromophores absorb the excitation light and emit visible light with longer wavelengths. The excitation light is then filtered out (in part because ultraviolet light is harmful to the eyes) so that only visible light passes through the ocular lens. This produces an image of the specimen in bright colors against a dark background.

Fluorescence microscopes are especially useful in clinical microbiology. They can be used to identify pathogens, to find particular species within an environment, or to find the locations of particular molecules and structures within a cell. Approaches have also been developed to distinguish living from dead cells using fluorescence microscopy based upon whether they take up particular fluorochromes. Sometimes, multiple fluorochromes are used on the same specimen to show different structures or features.

One of the most important applications of fluorescence microscopy is a technique called immunofluorescence, which is used to identify certain disease-causing microbes by observing whether antibodies bind to them. (Antibodies are protein molecules produced by the immune system that attach to specific pathogens to kill or inhibit them.) There are two approaches to this technique: direct immunofluorescence assay (DFA) and indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA). In DFA, specific antibodies (e.g., those that the target the rabies virus) are stained with a fluorochrome. If the specimen contains the targeted pathogen, one can observe the antibodies binding to the pathogen under the fluorescent microscope. This is called a primary antibody stain because the stained antibodies attach directly to the pathogen.

In IFA, secondary antibodies are stained with a fluorochrome rather than primary antibodies. Secondary antibodies do not attach directly to the pathogen, but they do bind to primary antibodies. When the unstained primary antibodies bind to the pathogen, the fluorescent secondary antibodies can be observed binding to the primary antibodies. Thus, the secondary antibodies are attached indirectly to the pathogen. Since multiple secondary antibodies can often attach to a primary antibody, IFA increases the number of fluorescent antibodies attached to the specimen, making it easier visualize features in the specimen (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)).

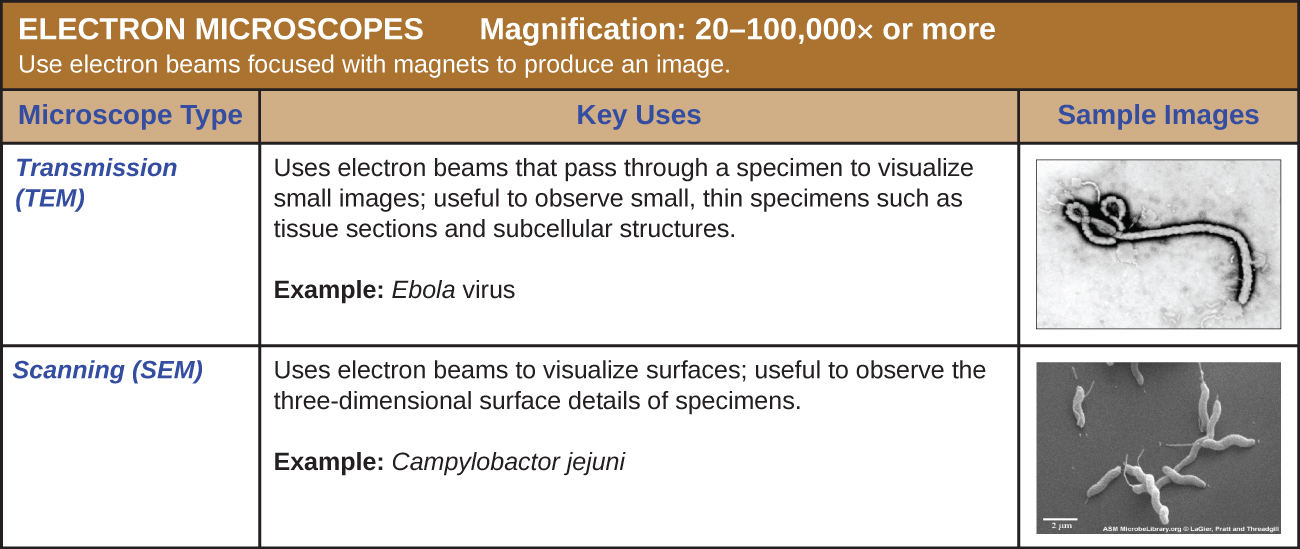

Electron Microscopy

The electron microscope was invented in 1931 by Max Knoll and Ernst Ruska at the Berlin Technische Hochschule, but it was not commercially available until 1938.

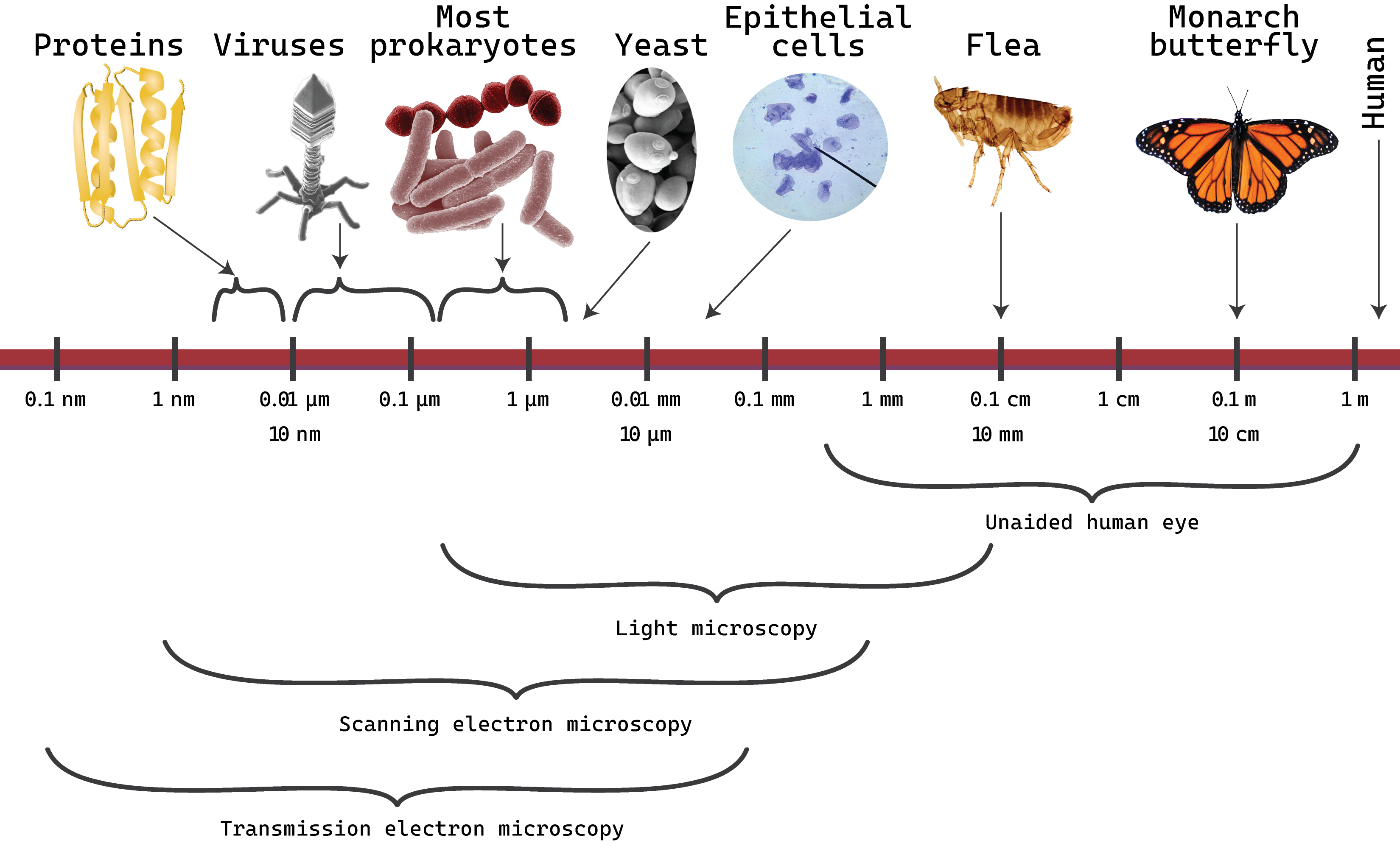

The maximum theoretical resolution of images created by light microscopes is ultimately limited by the wavelengths of visible light. Most light microscopes can only magnify 1000⨯, and a few can magnify up to 1500⨯, but this does not begin to approach the magnifying power of an electron microscope (EM), which uses short-wavelength electron beams rather than light to increase magnification and resolution.

Electrons, like electromagnetic radiation, can behave as waves, but with wavelengths of 0.005 nm, they can produce much better resolution than visible light. An EM can produce a sharp image that is magnified up to 100,000⨯. Thus, EMs can resolve subcellular structures as well as some molecular structures (e.g., single strands of DNA); however, electron microscopy cannot be used on living material because of the methods needed to prepare the specimens.

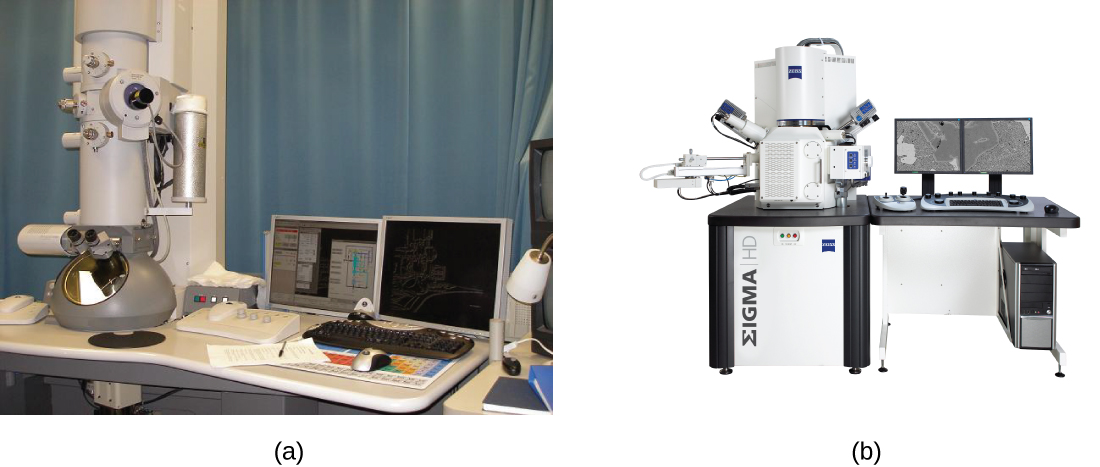

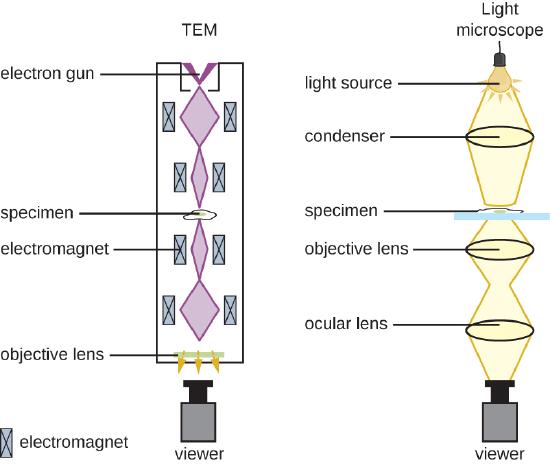

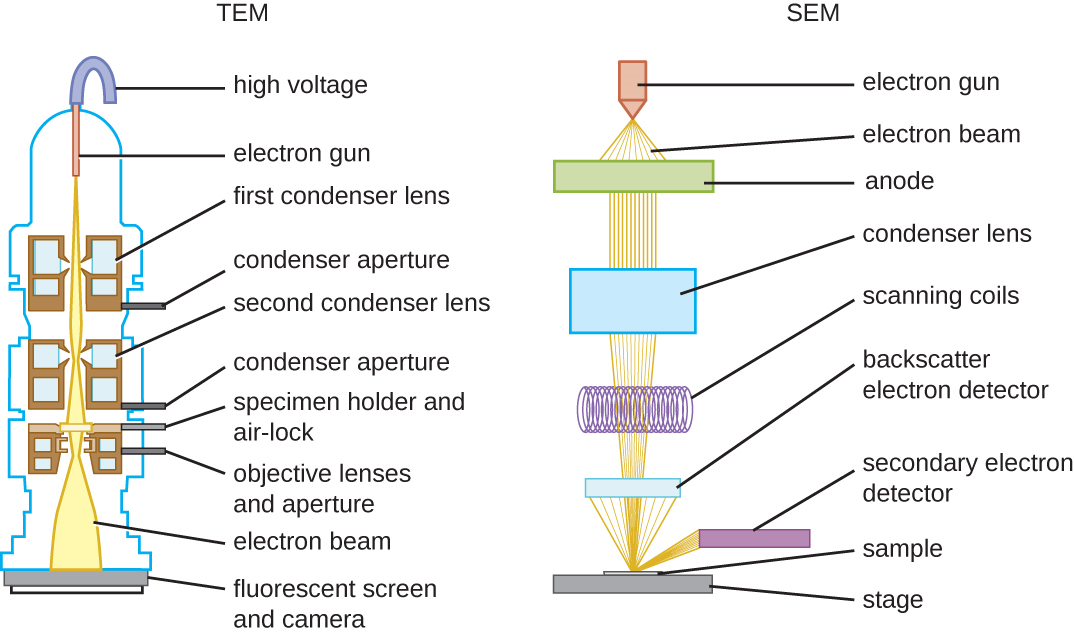

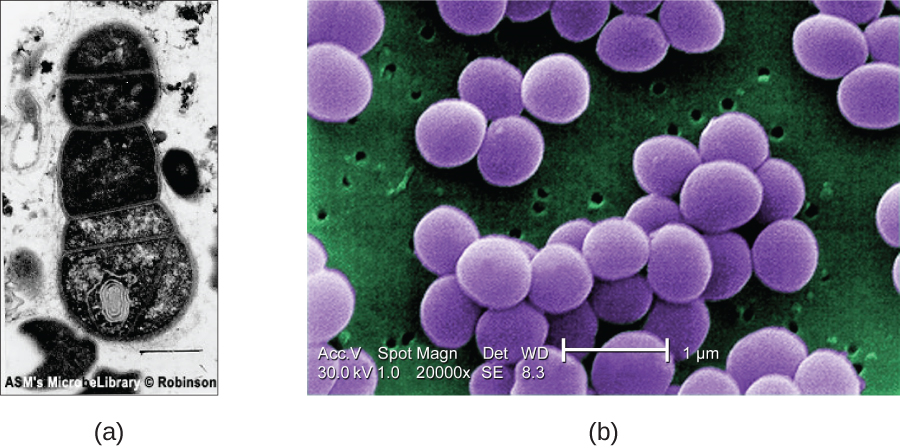

There are two basic types of EM: the transmission electron microscope (TEM) and the scanning electron microscope (SEM)(Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)). The TEM is somewhat analogous to the brightfield light microscope in terms of the way it functions. However, it uses an electron beam from above the specimen that is focused using a magnetic lens (rather than a glass lens) and projected through the specimen onto a detector. Electrons pass through the specimen, and then the detector captures the image (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)).

For electrons to pass through the specimen in a TEM, the specimen must be extremely thin (20–100 nm thick). The image is produced because of varying opacity in various parts of the specimen. This opacity can be enhanced by staining the specimen with materials such as heavy metals, which are electron dense. TEM requires that the beam and specimen be in a vacuum and that the specimen be very thin and dehydrated. The specific steps needed to prepare a specimen for observation under an EM are discussed in detail in the next section.

SEMs form images of surfaces of specimens, usually from electrons that are knocked off of specimens by a beam of electrons. This can create highly detailed images with a three-dimensional appearance that are displayed on a monitor (Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\)). Typically, specimens are dried and prepared with fixatives that reduce artifacts, such as shriveling, that can be produced by drying, before being sputter-coated with a thin layer of metal such as gold. Whereas transmission electron microscopy requires very thin sections and allows one to see internal structures such as organelles and the interior of membranes, scanning electron microscopy can be used to view the surfaces of larger objects (such as a pollen grain) as well as the surfaces of very small samples (Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\)). Some EMs can magnify an image up to 2,000,000⨯.1

Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\): Typical organism sizes and useful ranges of forms of microscopy. (2024; J. Kagle)

Exercise \(\PageIndex{5}\)

- What are some advantages and disadvantages of electron microscopy, as opposed to light microscopy, for examining microbiological specimens?

- What kinds of specimens are best examined using TEM? SEM?

Key Concepts and Summary

- Numerous types of microscopes use various technologies to generate micrographs. Most are useful for a particular type of specimen or application.

- Light microscopy uses lenses to focus light on a specimen to produce an image. Commonly used light microscopes include brightfield, darkfield, phase-contrast, differential interference contrast, fluorescence, confocal, and two-photon microscopes.

- Electron microscopy focuses electrons on the specimen using magnets, producing much greater magnification than light microscopy. The transmission electron microscope (TEM) and scanning electron microscope (SEM) are two common forms.

- Scanning probe microscopy produces images of even greater magnification by measuring feedback from sharp probes that interact with the specimen. Probe microscopes include the scanning tunneling microscope (STM) and the atomic force microscope (AFM).

Footnotes

- 1 “JEM-ARM200F Transmission Electron Microscope,” JEOL USA Inc, www.jeolusa.com/PRODUCTS/Tran...specifications. Accessed 8/28/2015.

Glossary

- atomic force microscope

- a scanning probe microscope that uses a thin probe that is passed just above the specimen to measure forces between the atoms and the probe

- binocular

- having two eyepieces

- brightfield microscope

- a compound light microscope with two lenses; it produces a dark image on a bright background

- coarse focusing knob

- a knob on a microscope that produces relatively large movements to adjust focus

- chromophores

- pigments that absorb and reflect particular wavelengths of light (giving them a color)

- condenser lens

- a lens on a microscope that focuses light from the light source onto the specimen

- confocal microscope

- a scanning laser microscope that uses fluorescent dyes and excitation lasers to create three-dimensional images

- darkfield microscope

- a compound light microscope that produces a bright image on a dark background; typically a modified brightfield microscope

- diaphragm

- a component of a microscope; typically consists of a disk under the stage with holes of various sizes; can be adjusted to allow more or less light from the light source to reach the specimen

- differential interference-contrast microscope

- a microscope that uses polarized light to increase contrast

- electron microscope

- a type of microscope that uses short-wavelength electron beams rather than light to increase magnification and resolution

- fine focusing knob

- a knob on a microscope that produces relatively small movements to adjust focus

- fluorescence microscope

- a microscope that uses natural fluorochromes or fluorescent stains to increase contrast

- fluorochromes

- chromophores that fluoresce (absorb and then emit light)

- illuminator

- the light source on a microscope

- immunofluorescence

- a technique that uses a fluorescence microscope and antibody-specific fluorochromes to determine the presence of specific pathogens in a specimen

- monocular

- having a single eyepiece

- objective lenses

- on a light microscope, the lenses closest to the specimen, typically located at the ends of turrets

- ocular lens

- on a microscope, the lens closest to the eye (also called an eyepiece)

- oil immersion lens

- a special objective lens on a microscope designed to be used with immersion oil to improve resolution

- phase-contrast microscope

- a light microscope that uses an annular stop and annular plate to increase contrast

- rheostat

- a dimmer switch that controls the intensity of the illuminator on a light microscope

- scanning electron microscope (SEM)

- a type of electron microscope that bounces electrons off of the specimen, forming an image of the surface

- scanning probe microscope

- a microscope that uses a probe that travels across the surface of a specimen at a constant distance while the current, which is sensitive to the size of the gap, is measured

- scanning tunneling microscope

- a microscope that uses a probe that is passed just above the specimen as a constant voltage bias creates the potential for an electric current between the probe and the specimen

- stage

- the platform of a microscope on which slides are placed

- total magnification

- in a light microscope is a value calculated by multiplying the magnification of the ocular by the magnification of the objective lenses

- transmission electron microscope (TEM)

- a type of electron microscope that uses an electron beam, focused with magnets, that passes through a thin specimen

- two-photon microscope

- a microscope that uses long-wavelength or infrared light to fluoresce fluorochromes in the specimen

- x-y mechanical stage knobs

- knobs on a microscope that are used to adjust the position of the specimen on the stage surface, generally to center it directly above the light

Contributor

Nina Parker, (Shenandoah University), Mark Schneegurt (Wichita State University), Anh-Hue Thi Tu (Georgia Southwestern State University), Philip Lister (Central New Mexico Community College), and Brian M. Forster (Saint Joseph’s University) with many contributing authors. Original content via Openstax (CC BY 4.0; Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction)