14.7: Classes in the Phylum Cnidaria

- Page ID

- 44729

- Identify the features of animals classified in class Anthozoa

- Identify the features of animals classified in class Scyphozoa

- Identify the features of animals classified in class Cubozoa

- Identify the features of animals classified in class Hydrozoa

Class Anthozoa

The class Anthozoa includes all cnidarians that exhibit a polyp body plan only; in other words, there is no medusa stage within their life cycle. Examples include sea anemones (Figure 1), sea pens, and corals, with an estimated number of 6,100 described species. Sea anemones are usually brightly colored and can attain a size of 1.8 to 10 cm in diameter. These animals are usually cylindrical in shape and are attached to a substrate. A mouth opening is surrounded by tentacles bearing cnidocytes.

The mouth of a sea anemone is surrounded by tentacles that bear cnidocytes. The slit-like mouth opening and pharynx are lined by a groove called a siphonophore. The pharynx is the muscular part of the digestive system that serves to ingest as well as egest food, and may extend for up to two-thirds the length of the body before opening into the gastrovascular cavity. This cavity is divided into several chambers by longitudinal septa called mesenteries. Each mesentery consists of one ectodermal and one endodermal cell layer with the mesoglea sandwiched in between. Mesenteries do not divide the gastrovascular cavity completely, and the smaller cavities coalesce at the pharyngeal opening. The adaptive benefit of the mesenteries appears to be an increase in surface area for absorption of nutrients and gas exchange.

Sea anemones feed on small fish and shrimp, usually by immobilizing their prey using the cnidocytes. Some sea anemones establish a mutualistic relationship with hermit crabs by attaching to the crab’s shell. In this relationship, the anemone gets food particles from prey caught by the crab, and the crab is protected from the predators by the stinging cells of the anemone. Anemone fish, or clownfish, are able to live in the anemone since they are immune to the toxins contained within the nematocysts.

Anthozoans remain polypoid throughout their lives and can reproduce asexually by budding or fragmentation, or sexually by producing gametes. Both gametes are produced by the polyp, which can fuse to give rise to a free-swimming planula larva. The larva settles on a suitable substratum and develops into a sessile polyp.

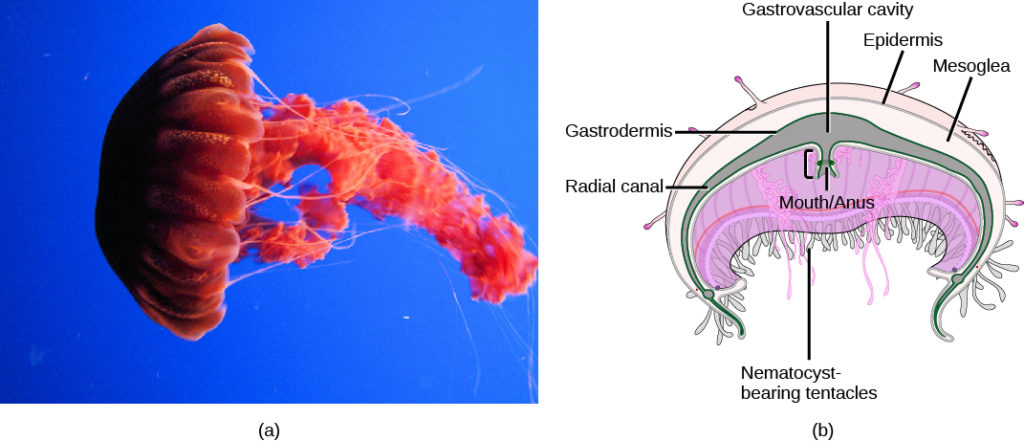

Class Scyphozoa

Class Scyphozoa includes all the jellies and is exclusively a marine class of animals with about 200 known species. The defining characteristic of this class is that the medusa is the prominent stage in the life cycle, although there is a polyp stage present. Members of this species range from 2 to 40 cm in length but the largest scyphozoan species, Cyanea capillata, can reach a size of 2 m across. Scyphozoans display a characteristic bell-like morphology (Figure 2).

In the jellyfish, a mouth opening is present on the underside of the animal, surrounded by tentacles bearing nematocysts. Scyphozoans live most of their life cycle as free-swimming, solitary carnivores. The mouth leads to the gastrovascular cavity, which may be sectioned into four interconnected sacs, called diverticuli. In some species, the digestive system may be further branched into radial canals. Like the septa in anthozoans, the branched gastrovascular cells serve two functions: to increase the surface area for nutrient absorption and diffusion; thus, more cells are in direct contact with the nutrients in the gastrovascular cavity.

In scyphozoans, nerve cells are scattered all over the body. Neurons may even be present in clusters called rhopalia. These animals possess a ring of muscles lining the dome of the body, which provides the contractile force required to swim through water. Scyphozoans are dioecious animals, that is, the sexes are separate. The gonads are formed from the gastrodermis and gametes are expelled through the mouth. Planula larvae are formed by external fertilization; they settle on a substratum in a polypoid form known as scyphistoma. These forms may produce additional polyps by budding or may transform into the medusoid form. The life cycle (Figure 3) of these animals can be described as polymorphic, because they exhibit both a medusal and polypoid body plan at some point in their life cycle.

Class Cubozoa

This class includes jellies that have a box-shaped medusa, or a bell that is square in cross-section; hence, are colloquially known as “box jellyfish.” These species may achieve sizes of 15–25 cm. Cubozoans display overall morphological and anatomical characteristics that are similar to those of the scyphozoans. A prominent difference between the two classes is the arrangement of tentacles. This is the most venomous group of all the cnidarians (Figure 4).

The cubozoans contain muscular pads called pedalia at the corners of the square bell canopy, with one or more tentacles attached to each pedalium. These animals are further classified into orders based on the presence of single or multiple tentacles per pedalium. In some cases, the digestive system may extend into the pedalia. Nematocysts may be arranged in a spiral configuration along the tentacles; this arrangement helps to effectively subdue and capture prey. Cubozoans exist in a polypoid form that develops from a planula larva. These polyps show limited mobility along the substratum and, like scyphozoans, may bud to form more polyps to colonize a habitat. Polyp forms then transform into the medusoid forms.

Class Hydrozoa

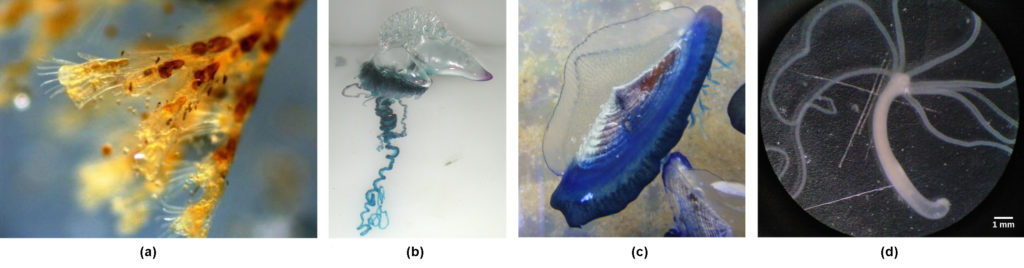

Hydrozoa includes nearly 3,200 species; most are marine, although some freshwater species are known (Figure 5). Animals in this class are polymorphs, and most exhibit both polypoid and medusoid forms in their life cycle, although this is variable.

The polyp form in these animals often shows a cylindrical morphology with a central gastrovascular cavity lined by the gastrodermis. The gastrodermis and epidermis have a simple layer of mesoglea sandwiched between them. A mouth opening, surrounded by tentacles, is present at the oral end of the animal. Many hydrozoans form colonies that are composed of a branched colony of specialized polyps that share a gastrovascular cavity, such as in the colonial hydroid Obelia. Colonies may also be free-floating and contain medusoid and polypoid individuals in the colony as in Physalia (the Portuguese Man O’ War) or Velella (By-the-wind sailor). Even other species are solitary polyps (Hydra) or solitary medusae (Gonionemus). The true characteristic shared by all of these diverse species is that their gonads for sexual reproduction are derived from epidermal tissue, whereas in all other cnidarians they are derived from gastrodermal tissue.

Contributors and Attributions

- Biology. Provided by: OpenStax CNX. Located at: http://cnx.org/contents/185cbf87-c72e-48f5-b51e-f14f21b5eabd@10.8. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/185cbf87-c72...f21b5eabd@10.8