13.22: Hox Genes

- Page ID

- 44000

Since the early nineteenth century, scientists have observed that many animals, from the very simple to the complex, shared similar embryonic morphology and development. Surprisingly, a human embryo and a frog embryo, at a certain stage of embryonic development, look remarkably alike. For a long time, scientists did not understand why so many animal species looked similar during embryonic development but were very different as adults. They wondered what dictated the developmental direction that a fly, mouse, frog, or human embryo would take.

Near the end of the twentieth century, a particular class of genes was discovered that had this very job. These genes that determine animal structure are called “homeotic genes,” and they contain DNA sequences called homeoboxes. The animal genes containing homeobox sequences are specifically referred to as Hox genes. This family of genes is responsible for determining the general body plan, such as the number of body segments of an animal, the number and placement of appendages, and animal head-tail directionality. The first Hox genes to be sequenced were those from the fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster). A single Hox mutation in the fruit fly can result in an extra pair of wings or even appendages growing from the “wrong” body part.

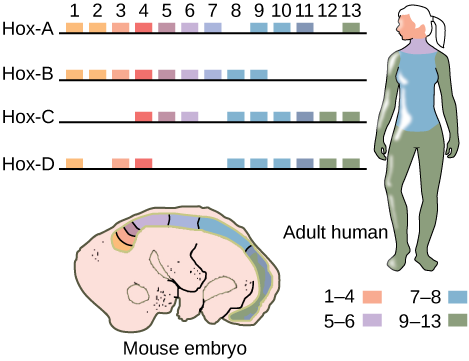

While there are a great many genes that play roles in the morphological development of an animal, what makes Hox genes so powerful is that they serve as master control genes that can turn on or off large numbers of other genes. Hox genes do this by coding transcription factors that control the expression of numerous other genes. Hox genes are homologous in the animal kingdom, that is, the genetic sequences of Hox genes and their positions on chromosomes are remarkably similar across most animals because of their presence in a common ancestor, from worms to flies, mice, and humans (Figure 1).

Hox genes are highly conserved genes encoding transcription factors that determine the course of embryonic development in animals. In vertebrates, the genes have been duplicated into four clusters: Hox-A, Hox-B, Hox-C, and Hox-D. Genes within these clusters are expressed in certain body segments at certain stages of development.

One of the contributions to increased animal body complexity is that Hox genes have undergone at least two duplication events during animal evolution, with the additional genes allowing for more complex body types to evolve.

Practice Question

If a Hox 13 gene in a mouse was replaced with a Hox 1 gene, how might this alter animal development?

[practice-area rows=”2″][/practice-area]

[reveal-answer q=”319959″]Show Answer[/reveal-answer]

[hidden-answer a=”319959″]The animal might develop two heads and no tail.[/hidden-answer]

Contributors and Attributions

- Biology. Provided by: OpenStax CNX. Located at: http://cnx.org/contents/185cbf87-c72e-48f5-b51e-f14f21b5eabd@10.8. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/185cbf87-c72...f21b5eabd@10.8