11.4: Overharvesting

- Page ID

- 71489

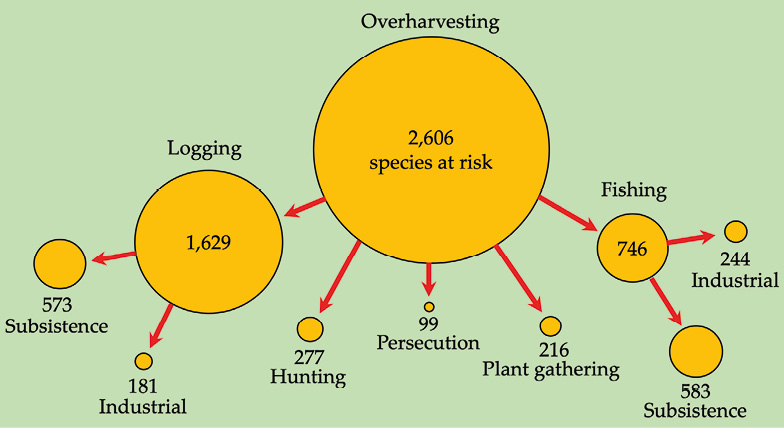

People have always hunted, collected, trapped, or otherwise harvested the food and other natural resources they need to survive. When human populations were small, at least relative to the abundance of their resources, and collection methods were relatively unsophisticated, people could sustainably harvest and hunt wildlife in their local environments. However, as human populations have increased, and roads have provided access to previously remote areas, our impact on the environment has escalated. At the same time, our methods of harvesting have become dramatically more efficient. Guns are now used instead of blowpipes, spears, or arrows, while networks of wire snares indiscriminately catch animals of all types, even young and pregnant females. Populations of species that mature and reproduce rapidly can often recover quickly after harvests and can thus be exploited sustainably; however, species that are slow-maturing and slow-reproducing cannot sustain current harvest levels. Consequently, many species are threatened due to overharvesting (overexploitation), the unsustainable collection of natural resources (Maxwell et al., 2016). Overharvesting may take on many forms, including hunting, fishing, logging, and gathering of plants and animals for medicine, captive collections, subsistence, commerce, or recreation purposes (Figure 11.3.1).

Terrestrial Animals

Terrestrial animals may be overexploited as sources of food, garments, jewelry, medicine, or pets. For example, the poaching of elephants for their valuable ivory and rhinos for their horns, which are used in traditional medicine, is a major threat to these species. There are also concerns about the effect of the pet trade on some terrestrial species such as turtles, amphibians, birds, plants, and even the orangutans. Harvesting of pangolins for their scales and meat, and as curiosities, has led to a drastic decline in population size (figure 11.3.2).

Figure 11.3.2: Pangolins are threatened by overexploitation. This work by David Brossard is licensed under CC-BY.

The Bushmeat Crisis

Bushmeat—wild sources of protein obtained on land by hunting and collecting birds, mammals, snails, and caterpillars—provides much of the protein in people’s diets in many parts of the world. These hunting practices, particularly in equatorial Africa and parts of Asia, are believed to threaten several species with extinction. Traditionally, bush meat in Africa was hunted to feed families directly. However, recent commercialization of the practice now has bush meat available in grocery stores, which has increased harvest rates to the level of unsustainability. Additionally, human population growth has increased the need for protein foods that are not being met from agriculture. Species threatened by the bush meat trade are mostly mammals including many monkeys and the great apes living in the Congo basin. For example, more than 9,000 primates are killed annually for a single market in Côte d’Ivoire (Covey and McGraw, 2014); people from Central Africa harvest an astonishing 5.3 million tons of mammalian bushmeat annually (Fa et al., 2002). Usually seen as a conservation challenge in Africa’s tropical forests, the bushmeat crisis also impacts savannah regions (reviewed in Lindsey et al., 2013)where bushmeat hunters, numbering between 1,500 and 2,000, remove over 600,000 kg of herbivore biomass from Botswana’s Okavango Delta each year, despite the region’s protected status and importance for ecotourism sectors (Rogan et al., 2017).

Very few animal populations can withstand such high extraction rates. Consequently, regions dependent on bushmeat have already seen substantially wildlife declines (Lindsey et al., 2013). At current exploitation rates, supplies are expected to decrease by an additional 80% within the next 50 years (Fa et al., 2003). Unless more sustainable, alternative sources of protein are found, people dependent upon bushmeat will see increased malnutrition and compromised livelihoods as bushmeat species are pushed to extinction. When that happens, families relying on bushmeat will face even worse food insecurity than that which is driving the current bushmeat crisis.

Exacerbating the risk of food insecurity, people in the affected regions will also suffer from compromised ecosystem services as populations of predators, seed dispersers, and pollinators are reduced (Rosin and Poulsen, 2016). For example, reduced mammal populations have been linked to reduced abundance of fruits and other useful plant products available for human consumption (Vanthomme et al., 2010). Some areas are already suffering from “empty forest syndrome”—a condition where a forest appears to be green and healthy, but is practically devoid of animals, and in which ecological processes have been irreversibly altered such that the forest’s species composition will change over subsequent decades (Nasi et al., 2011; Benítez-López et al., 2019). The bushmeat crisis is thus a major concern to people concerned about biodiversity and/or human well-being.

The impact of traditional medicine

As the human population has increased, so has the demand for traditional medicine. Today, harvesting for traditional medicine is putting unsustainable pressure on species exploited for this purpose (Williams et al., 2014). One prominent example is vultures: the demand of vulture body parts, believed to bestow clairvoyant abilities, is driving massive vulture population declines across Africa. The growth in traditional medicine markets in East Asian countries such as China, Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam exacerbates these problems. For example, as tigers (Panthera tigris, EN) and rhinoceros have become scarce in Asia, Asian traditional healers are increasingly targeting African predators and rhinoceros to satisfy their market demands. Another group of species threatened by the Asian traditional medicine trade is sea horses (Hippocampus spp.). Due to population declines from overharvesting, sea horse exports from Kenya and Tanzania to East Asia have halved over recent years; yet, more than 600 kg of dried sea horses (over 254,000 individuals) continue to be exported annually (McPherson and Vincent, 2004). Exploitation for Asian traditional medicine markets has already pushed the western black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis longipes, EX) to extinction. In a similarly perilous position is the northern white rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum cottoni, CR); with only two non-reproductive females left in the world, this species is now considered committed to extinction. A group of species sought after by both African and Asian traditional medicine markets is pangolins, thought to be the most heavily poached animals on Earth. For example, between 2012 and 2016, more than 20 tons of African pangolin scales (involving up to 30,000 animals) were seized during law enforcement operations across the region (Andersen, 2016). The problem is also getting worse: authorities intercepted 13 tons of scales in Singapore in 2019, all from a single shipment believed to travel from Nigeria to Vietnam (Geddie, 2019). With such a large active operational scale, it comes as no surprise that all four African pangolin species are now threatened with extinction (IUCN, 2019).

The impact of live animal trade

Millions of non-domesticated animals are sold as pets around the world each year (Table 11.3.1). Given that many of these pets were originally collected in the wild, it is no surprise that the most popular species tend to be at a high risk of extinction (Bush et al., 2014). These huge numbers are magnified by the extra millions of animals needed to compensate for deaths during collection and shipping. Collection of wild animals for pets and other purposes has a massive impact of biodiversity around the world.

Coral reefs are extremely diverse marine ecosystems that face peril from several processes. Reefs are home to 1/3 of the world’s marine fish species—about 4,000 species—despite making up only one percent of marine habitat. Most home marine aquaria house coral reef species that are wild-caught organisms—not cultured organisms. 82 of the 291 species of African freshwater fish known to occur in the pet trade are considered threatened with extinction (UNEP-WCMC, 2008).

Among the most popular groups of wildlife traded are Africa’s parrots (Figure 11.3.3). For example, 32,000 wild-sourced African grey parrots (Psittacus erithacus, EN) were imported into the European Union in 2005 (UNEP-WCMC, 2007). Combined with habitat loss, the wild bird trade has already caused extirpations of this species in some areas of West Africa (Annorbah et al., 2015). While it is true that collecting wild animals for the pet trade sustains many people’s livelihoods, research on harvesting of ornamental fish has shown that this practice is not sustainable in the long term (Brummet et al., 2010). It is therefore critical to find ways to make these practices more sustainable, for the sake of the pet collectors and biodiversity.

|

Group |

Number traded each year |

Notes |

|---|---|---|

|

Orchids |

250 million |

Mainly cultivated, but about 10% sourced from the wild. Illegal trade—and mislabeling to avoid regulation—a major problem. |

|

Succulent plants |

35 million |

Mainly cultivated, but about 15% sourced from the wild. Illegal trade remains a major problem. |

|

Corals |

13 million |

Collected using destructive methods; used for aquarium decor and jewelry. |

|

Reptiles |

7.2 million |

Mainly sourced from the wild for zoos and pet trade, but increasingly from farms. Does not include large skin trade. |

|

Birds |

2.3 million |

Mostly perching birds destined for zoos and pet trade. Also includes legal and illegal trade of parrots. |

|

Ornamental fish |

2 million |

Most originate from wild reefs, caught by illegal methods that damage the surrounding coral reef and other wildlife. |

|

Primates |

148,000 |

Used for biomedical research, while many also destined for pets, circuses, zoos, and private collections. |

Sources: http://cites-dashboards.unep-wcmc.org, data presented as live specimens exported from 2011–2015. Data generally do not include illegal traded specimens, which are usually not reported to CITES.

Overfishing

Pressure on biodiversity in aquatic environments is also increasing as people continue to harvest fish, sea turtles, dolphins, shellfish, and manatees for meat at increasing rates. For about one billion people, aquatic resources provide their main source of animal protein. Modernized fishing methods play a major role in the decline of biodiversity (Figure 11.3.4). Also, in the marine environment, motorized fleets and enormous factory ships can now spend months at sea where they catch fish to sell at local and global markets (Ramos and Grémillet, 2013; Pauly et al., 2014). Some estimates suggest that wild-caught seafood could be virtually absent by 2050 if current exploitation levels persist (Worm et al., 2006).

Figure 11.3.4: Fishing boats at marine fishers. Alaskan waters have been fished by people for thousands of years, but they are under pressure from modern fishing technologies and large-scale extraction. Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

For many aquatic organisms, the indirect impacts of modern commercial fishing methods outweigh direct exploitation (Figure 11.3.5). One example is ghost fishing, which causes thousands of animals to die each year after becoming entangled in dumped, abandoned, and lost fishing gear. Similarly, approximately 25% of fish harvests are considered bycatch—animals that are accidentally caught, injured, or killed during fishing operations. Recent declines in skates, rays, turtles, sharks, dolphins, and seabirds have all been linked to incidental deaths as bycatch (Cox et al., 2007; Carruthers et al., 2009).

Figure 11.3.6 illustrates the extent of overfishing in the U.S. Despite considerable effort, few fisheries are managed sustainability. For example, the western Atlantic cod fishery was a hugely productive fishery for 400 years, but the introduction of modern fishing vessels in the 1980s and the pressure on the fishery led to it becoming unsustainable. Bluefin tuna are in danger of extinction. The once-abundant Mediterranean swordfish fishery have been depleted to commercial and biological exhaustion.

Figure 11.3.6: Map of overfishing and overfished stocks in the U.S. by region. Stocks on the overfishing list are being harvested too quickly, and those on the overfished list have population sizes that are too low. For example, stocks of Chinook salmon, Coho salmon, and Pacific sardines are overfished in the Pacific. Some species, including stocks of Pacific bluefin tuna and Atlantic cod, are on both the overfishing and overfished lists. Image by NOAA (public domain).

Most fisheries are managed as a common resource, available to anyone willing to fish, even when the fishing territory lies within a country’s territorial waters. Common resources are subject to an economic pressure known as the tragedy of the commons, in which fishers have little motivation to exercise restraint in harvesting a fishery when they do not own the fishery. This results on overexploitation. In a few fisheries, the biological growth of the resource is less than the potential growth of the profits made from fishing if that time and money were invested elsewhere. In these cases—whales are an example—economic forces will drive toward fishing the population to extinction.

Overfishing can result in a radical restructuring of the marine ecosystem in which a dominant species is so overexploited that it no longer serves its ecological function. For example, overfishing a tertiary consumer could causes populations of secondary consumers to increase. Secondary consumers would then feed on primary consumes (like zooplankton), decreasing their population size. With fewer zooplankton, populations of primary producers (phytoplankton, or photosynthetic microorganisms) would be unregulated (see Food Chains). The collapse of fisheries has dramatic and long-lasting effects on local human populations that work in the fishery. In addition, the loss of an inexpensive protein source to populations that cannot afford to replace it will increase the cost of living and limit societies in other ways. In general, the fish taken from fisheries have shifted to smaller species, and the larger species are overfished. The ultimate outcome could clearly be the loss of aquatic systems as food sources.

Overharvesting of plant products

Some plant and fungal species are also overexploited, particularly if they are slow-growing. While legal and illegal timber and firewood extraction is a major source of deforestation throughout parts of the world, it is also an important extinction driver. In fact, logging and other forms of wood harvesting have already contributed to the extinction of at least six plant species in Sub-Saharan Africa, with an additional 116 species considered Critically Endangered in part due to these threats (IUCN, 2019). Other plant species face extinction due to exploitation for medicines, spices, fragrances, and ornaments. For example, White’s ginger (Mondia whitei)—reputed to have aphrodisiac and antidepressant properties—has been harvested to extirpation in parts of central Kenya and South Africa (Aremu et al., 2011). Similarly, harvesting rates of African blackwood (Dalbergia melanoxylon, NT)—popular for making musical instruments and fine furniture—are currently unsustainable because the tree is slow-growing, has low germination rates, and extractions are seldom offset with planting of new seeds or seedlings (Amri et al., 2009). In addition, stocks of wild ginseng, which is valued for its health benefits, are dwindling. Peyote cactus, which causes hallucinations and is used in sacred ceremonies, is also declining. Yarsagumba, dead moth larvae that were infected by fungal parasites (caterpillar fungus, Ophiocordyceps sinensis), is overexploited because it is highly valued in traditional medicine and used as an aphrodisiac (figure 11.3.7).

Figure 11.3.7: Yarsagumba is a combination of moth larvae and the fungus that infected and killed it. Image by Punya (CC-BY-SA).

Challenges in managing overharvesting

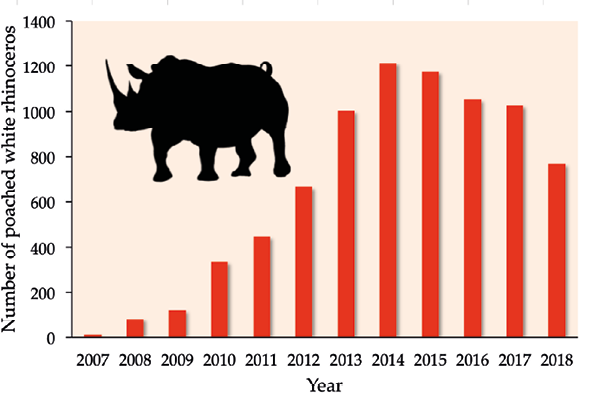

One of the biggest challenges in combating overharvesting is the non-enforcement and/or outright absence of legal controls to protect exploited species. But even where strong regulatory frameworks exist, the sheer scale of the problem poses practical challenges for effective enforcement, as billions of dollars flow among participants in illegal wildlife trade, which include local people trying to make a living, professional poachers, corrupt government officials, unethical dealers, and wealthy buyers who are not concerned about how the wildlife products they use were obtained. The illegal wildlife trade has hit Africa’s megafauna particularly hard. For example, even though there has been an international ban on the ivory trade since 1989, thousands of African elephants continue to be illegally killed on an annual basis (Box 11.3.1). Similarly, despite a ban on rhinoceros horn trade since 1977, an increasing number of rhinoceros succumb to poaching every year (Figure 11.3.8). Worse yet, the illegal wildlife trade shares many characteristics and practices with the illegal trade in drugs and weapons; in some cases, the same syndicates run these various criminal enterprises (Christy and Stirton, 2015). Apprehending these criminal networks is generally very dangerous, requiring vast resources.

Figure 11.3.8 More than 7,200 rhinoceros were illegally killed in South Africa between 2007 and 2017. Fortunately, illegal killings have declined in recent years, thanks to massive anti-poaching campaigns and increased law enforcement efforts. Source: SADEA, CC BY 4.0.

David H.M. Cumming

FitzPatrick Institute of African Ornithology, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa.

Tropical Resource Ecology Programme, University of Zimbabwe, Harare, Zimbabwe.

As our increasingly human-dominated planet enters a new geological era, will there still be room for Earth’s largest land mammals? Or will there be, as happened to mammoths, sabre-toothed cats, and giant sloths during the Pleistocene, another hominid-induced extinction of large mammals? Our new human-dominated era has become known as the Anthropocene (Waters et al., 2015), and the animals are, of course, Africa’s elephants.

Elephants encapsulate the dilemmas of conserving large charismatic mammals. They are dominant ecosystem engineers that, depending on their densities, can facilitate or adversely impact species diversity and ecosystem processes. They are also economically important to ecotourism industries and revered by many; ivory ornaments and carvings have been valued highly by many cultures past and present. But elephants are also regarded as dangerous pests by expanding small-scale farming communities, responsible for destroying crops and killing people. While retaliatory killings and habitat loss (primarily through agricultural expansion) certainly contribute to the endangerment of elephants, poaching to supply Asian markets is the primary cause behind massive population reductions we are currently witnessing (Wittemyer et al., 2014).

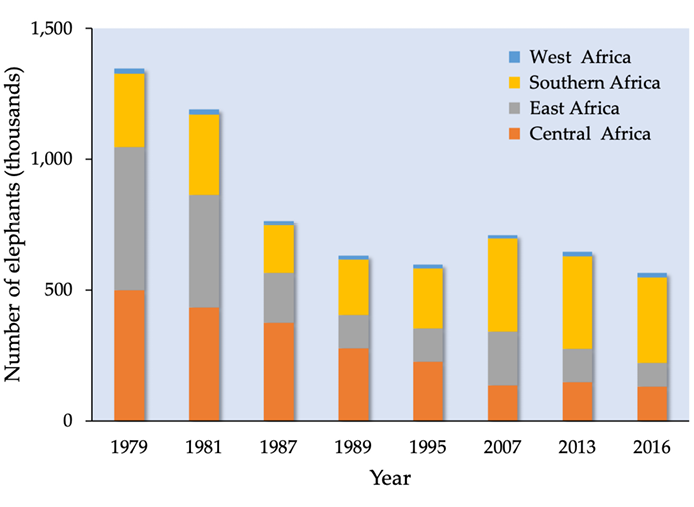

Africa’s elephants have, in the past, been greatly exploited, first for their meat and later also for their ivory. In 1887, about 1,000 tonnes of ivory were being exported from Africa (Spinage, 1973) and, by 1900, elephant populations in many African countries had all but collapsed. In Southern Africa, for example, it was feared that they might soon go extinct. However, with effective protection, elephant populations increased twentyfold, to more than 200,000, south of the Zambezi River by the 1970s. Elsewhere, elephant numbers also recovered, and, in the mid-1970s, the continental elephant population was estimated to be more than 1 million. But a rapid escalation of the illegal killing of elephants for ivory and meat soon followed, accompanied by a steep rise in the price of ivory. In response, African elephants were placed on CITES Appendix II in 1976 to control the international trade in ivory. Elephants in some Southern African countries were well protected, so numbers continued to grow. However, elsewhere poaching and illegal trade in ivory continued and, in 1989, the African elephant was placed on CITES Appendix I, which banned all international trade in elephants and elephant products. The result was a decline in the price of ivory, and recovery of many populations.

Conservationists, and the world at large, traditionally regarded the African elephant as a single species. Recent morphometric and genetic evidence has revealed that forest and savannah elephants represent two distinct species, with forest elephants (Loxodonta cyclotis) occupying the West and Central African forests, and the larger savannah elephants (Loxodonta africana) being widespread in non-forested regions of Sub-Saharan Africa (Roca et al., 2015). The distinction has important implications for their conservation, as each of these elephant species now viewed on its own is even more sensitive to population declines (CBD, 2015).

Since about 2006, poaching of elephants again began to escalate, in part a response to an increase in the price of ivory, poorly funded wildlife agencies, and corruption (Hauenstein et al., 2019). The scale of these killings is extraordinary. For example, an estimated 30,000 elephants were killed in 2013 alone. Forest elephants declined by about 60% (Maisel et al., 2013). While population trends for savannah elephants vary across the region, they too face increased poaching pressure (Chase et al., 2016). Due to these large-scale killings, combined with the impact of habitat loss from agricultural expansion, West Africa’s elephants are today confined to small isolated protected areas with a total population of about 17,000 (Maisel et al., 2013). Elephant population trends in East Africa vary: numbers are increasing in Uganda and Kenya, but Tanzania has lost some 60,000 elephants in the last few years. In Southern Africa, Botswana has the largest elephant population, estimated in 2014 to number at least 130,000. Neighboring Zimbabwe has a population of 83,000 elephants, much the same number as it had in 2001. However, two of Zimbabwe’s four regional populations declined significantly between 2006 and 2014 with a loss of at least 20,000 elephants (Figure 11.3.9).

Global and national efforts to curb elephant poaching are currently focused on improving law enforcement on the ground, intercepting ivory shipments to Asia, closing ivory markets in Africa and Asia, and leading campaigns to reduce demand for ivory in major consuming countries in Asia, particularly in China. Importantly, while these initiatives are relieving poaching pressure on African elephant populations, they fail to address core issues relating to the interactions between people and elephants in the rural areas of Africa. A high proportion of elephant ranges lie outside protected areas where they overlap with people. Relieving continued pressures on elephants, outside as well as inside protected areas, would only happen if people who are harmed by elephants derive enough benefits from elephants and other wildlife to outweigh the direct and indirect costs of sharing land with them. Community-based natural resource management (CBNRM) projects, such as those in Namibia show that this can be achieved. Establishing secure and sustainable funding streams through payments for ecosystem services, or payments for co-existing with large dangerous mammals such as elephants, could extend these promising initiatives even further.

Attributions

Modified by Amie Mazzoni Frazer from the following sources:

- Overexploitation from Environmental Science contributed by Melissa Ha and Rachel Schleiger (licensed under CC-BY)

- Overharvesting from Conservation Biology in Sub-Saharan Africa by John Wilson and Richard Primack

- Threats to Biodiversity and Importance of Biodiversity from Environmental Biology by Matthew R. Fisher (licensed under CC-BY)

- Threats to Biodiversity from General Biology by OpenStax (licensed under CC-BY)

- Case Study: Marine Fisheries from Sustainability: A Comprehensive Foundation by Tom Theis and Jonathan Tomkin, Editors. Download for free at CNX. (licensed under CC-BY)

- Understanding Bycatch. NOAA Fisheries. Accessed 28 March 2021 (public domain)