23.5: Infancy

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 22629

What a Life!

Sleep, cry, eat, repeat. Oh, the life of an infant. Newborn infants actually do spend most of their time in these three “pursuits.” However, by the end of their first year, they have greatly expanded their repertoire. By their first birthday, infants are typically starting to walk and talk, and they are spending about as much time awake as asleep. Clearly, infancy is a time of tremendous change.

Defining Infancy

Infancy refers to the first year of life after birth, and an infant is defined as a human being between birth and the first birthday. The term baby is usually considered synonymous with an infant, although it is commonly applied to the young of other animals, as well as humans. Human infants seem weak and helpless at birth, but they are actually born with a surprising range of abilities. Most of their senses are quite well developed, and they can also communicate their needs by crying, like the three-day-old baby in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\). During their first year, infants develop many other abilities, some of which are described in this concept. They also grow more rapidly during their first year than they will at any other time during the rest of their life.

Neonate

A newborn infant is called a neonate up until the first four weeks after birth. A neonate, like the crying baby pictured in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\), does not usually look like the plump, chubby-cheeked “Gerber baby” that most people envision when they hear the term "baby."

Status of the Newborn: Apgar Score

Immediately after birth, a simple test called an Apgar test, is administered to an infant to evaluate its transition from the uterus to the outside world (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). The newborn is assessed on each of five easy-to-measure traits, and for each trait is given a score of 0, 1, or 2 (where 0 is the worst value and 2 is the best). After an infant is assessed on each trait, the values of all five traits are added together to yield the Apgar score. The highest (best) possible score is 10, but a score of 7 or higher is considered normal. A score of 4-6 is considered fairly low, and a score of 3 or lower is considered critically low. The purpose of the Apgar test is to determine quickly whether a newborn needs immediate medical care. It is not designed to predict long-term health issues.

The five traits that are assessed in an Apgar test are listed in Table \(\PageIndex{1}\). The table also shows how the acronym APGAR can be used to help remember the five traits.

| Acronym (APGAR) | Trait | Score of 0 | Score of 1 | Score of 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A = Appearance | skin color | blue or pale all over | blue at extremities; body pink | extremities and body both pink |

| P = Pulse | heart rate | absent | <100 beats per minute | >100 beats per minute |

| G = Grimace | reflex irritability grimace | no response to stimulation | the grimace on suction or aggressive stimulation | cry on stimulation |

| A = Activity | activity | none | some flexion | flexed arms and legs that resist extension |

| R = Respiration | respiratory effort | absent | weak, irregular gasping | strong, robust cry |

Umbilical Cord

The umbilical cord of a newborn infant contains the umbilical artery and vein. The cord will normally be cut within seconds of birth, leaving a stub about 3-5 cm (1-2 in.) long (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)). The umbilical stub will dry out, shrivel, darken, and spontaneously fall off within about three weeks of birth. This will become the navel after it fully heals.

Physical Characteristics of the Neonate

Right after birth, a newborn’s skin is wet. It may be covered with streaks of blood, and coated with patches of waxy white vernix. The newborn may also have peeling skin on the wrists, hands, ankles, and feet. Some newborns still have the fine, colorless hair called lanugo, but it usually disappears within the first month after birth. Infants may be born with a full head of hair, or they may have very little hair, or even be bald. A newborn’s body proportions are distinctive, as well. The shoulders and hips are relatively wide, and the arms and legs are relatively long compared to the rest of the body. In addition, the abdomen protrudes slightly.

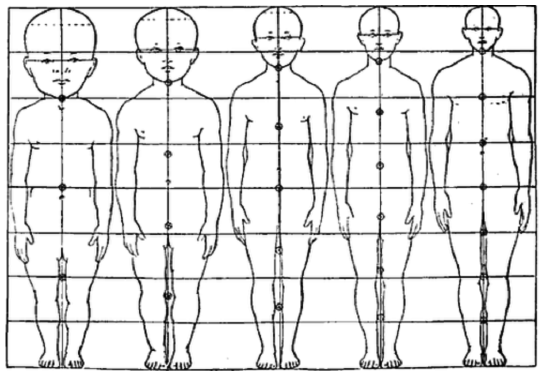

A newborn’s head, especially the cranium, is very large in proportion to the body. As shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\), the newborn head makes up about one-quarter of the baby’s total body length, whereas the head of an adult makes up only about one-seventh of the adult’s total body length. The body is drawn to be the same length (height) at each age to make the differences in body proportion — and especially head size — more apparent.

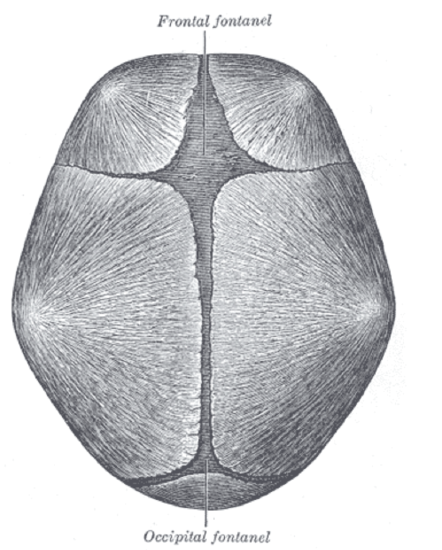

Many regions of the neonate’s skull have not yet been converted to bone, leaving “soft spots” known as fontanels (Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\)). The two largest fontanels are the diamond-shaped anterior (frontal) fontanel, located at the top front of the skull, and the smaller triangular-shaped posterior (occipital) fontanel, located at the back of the head. During birth, the fontanels enable the bony plates of the skull to move and change shape, allowing the child's head to pass through the birth canal. Right after birth, the head may be temporarily misshapen for this reason. The ossification of the bones of the skull causes the posterior fontanel to close during the first two or three months after birth, and the anterior fontanel to close by nine to 18 months after birth.

Size and Growth of the Neonate

In the wealthier nations of the world, the total body length of a full-term infant at birth normally ranges between 46 and 56 cm (18 and 22 in.), with an average of 51 cm (20 in.). The birth weight of a full-term infant normally ranges from 2.5 to 4.5 kg (5.5 to 10 lb), with an average of 3.4 kg (7.5 lb). For pre-term infants, these numbers are likely to be lower, because these infants have had a shorter period of prenatal growth.

During the first week following birth, it is normal for the weight of a neonate to decrease by about three to seven percent of the birth weight. For example, a baby born at an average weight of 3.4 kg (7.5 lb) might weigh only 3.2 kg (7.1 lb) by the seventh day after birth. This loss of weight is a normal result of the resorption and urination of the fluid that initially fills the lungs. A contributing factor may be a delay of a few days before feeding becomes well established, which is also normal. After the first week, a healthy neonate should start to gain up to 20 g (0.7 oz) per day.

Neonate Senses

Some senses in newborns are already relatively well developed. Other senses are still immature and need to develop further after birth.

Sense of Touch in the Neonate

Newborns have a well-developed sense of touch, and they usually respond positively to soft stroking and cuddling. Gentle rocking back and forth, massages, and warm baths are also positively received by neonates, and they may calm a crying infant. Newborns can often comfort themselves by sucking their thumb, finger, or pacifier.

Vision in the Neonate

Newborns' vision is not yet fully developed. Both the retinas and the parts of the brain involved in vision are still immature. Most newborns are only able to focus on objects that are directly in front of their face and about 46 cm (18 in.) away. However, this is sufficient for the infant to see the mother’s face, as well as the areola and nipple. When a newborn is not feeding, sleeping, or crying, it is generally staring at objects within its visual range. Usually, anything that is shiny has sharp contrasting colors, or has a complex pattern will catch an infant’s eye. However, the neonate, like the infant pictured in Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\), has a clear preference for looking at human faces above all else.

Newborns have limited color perception. About three-quarters of newborns can distinguish red, but fewer than half can distinguish green, yellow, or blue. Color perception, however, improves quickly after birth. A newborn infant also lacks depth perception, which is the ability to see in three dimensions. This ability starts to develop only after an infant becomes mobile later in infancy. It continues to develop throughout early childhood.

Hearing in the Neonate

A sense of hearing is well developed at birth. Newborns usually respond more readily to female than male voices, and the sound of voices, especially the mother’s voice, may have a soothing effect on the infant. Sounds that the infant heard before birth — such as the parent’s breathing and heartbeat — are also comforting to the newborn.

Loud or sudden noises, on the other hand, are likely to startle and frighten a newborn. The neonate also responds to sounds of potential danger — such as angry voices of adults, thunder, or the cries of other infants — with greater attention. They may turn toward the sounds and blink their eyes.

Taste and Smell in the Neonate

Newborns can respond to different tastes, including sweet, sour, bitter, and salty tastes. They generally show a preference for sweet tastes. They also show a preference for the smell of foods that their mother ate regularly during pregnancy. Presumably, this occurs because amniotic fluid changes taste with different foods eaten by the mother.

Newborn Reflexes

Newborns have a number of instinctive behaviors, or reflexes, that help them survive. Crying is one example. It is instinctive in newborn infants, who may use it to express a variety of feelings, such as hunger, discomfort, overstimulation, or loneliness. The need to suckle is also instinctive. They have a sucking reflex that allows them to extract milk from the mother’s nipple or from the nipple on a bottle right after birth. In addition, infants have an instinctive behavior known as the rooting reflex that helps them find the nipple by touch. When an infant’s cheek is stroked or it rubs against an object, the baby automatically turns its head in that direction to find the nipple.

Infants are born with other reflexes that aid them in maintaining close physical contact with their caregiver. These reflexes help them hold onto the caregiver so they are less likely to fall, and also so they can satisfy their basic need for constant physical contact. Two of these reflexes are the Moro reflex and the grasping reflex.

- The Moro reflex is an instinctive behavior that is normally present in an infant from birth up until about three or four months of age. It occurs in response to a sudden loss of support when the infant feels as though it is falling. It involves three distinct components: suddenly spreading out the arms, bringing the arms back in toward the body, and, usually, crying. If the baby really were falling, these motions might help it reach out and grab its mother or another caregiver.

- The grasping reflex is the instinctive grasping of a finger or other object that is placed in the palm of an infant. This reflex actually arises before birth and is present until an infant is about five or six months of age. It may help an infant grip and hang on to the mother or another caregiver.

Milestones in Infant Development

Many developments occur during infancy. These include developments in several areas — motor skills, sensory abilities, and cognitive abilities. Infants vary in the exact timing of these developments, but the sequence of the developments is usually similar from one infant to another.

Two Months

During the first two months after birth, an infant normally develops the ability to hold their head erect and steady when they are held in an upright position. They will also develop the ability to roll from their side to their back. They are likely to start cooing and babbling at their parents and other people they know, and they will also start smiling at their parents (Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\)).

Four Months

By the end of the fourth month after birth, an infant can roll from front to side, lift their head 90 degrees while lying prone, sit up with support, and hold their head steady for brief periods. They will turn their head toward sounds and follow objects with their eyes. They will start to make vowel sounds and begin to laugh. They may even squeal with delight.

Six Months

Around six months of age, an infant is normally able to pick up objects and transfer them from hand to hand. They can also pull themselves into a sitting position. Their vision will have improved so it is now almost as acute as adult vision. The infant will also start noticing colors and start to show the ability to discriminate depth. They are likely to enjoy vocal play and may start making two-syllable sounds such as “mama” or “dada.” They may also start to show anxiety toward strangers.

Ten Months

By about ten months of age, an infant can wiggle and crawl, like the infant pictured in Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\), and can sit unsupported. If they drop a toy they will look for it, and they can now pick up objects with a pincer grasp (using the tips of the thumb and forefinger). They babble in a way that starts to resemble the cadences of speech. They are likely to exhibit fear around strangers.

Twelve Months

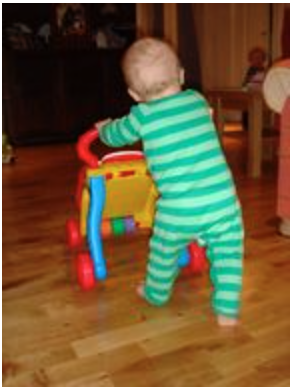

By the end of the first year, an infant normally can stand while holding onto furniture or someone’s hand. They may even be starting to walk, as the infant in Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\). When they drop toys, they watch where the toys go. The babies may cooperate with dressing, and they may wave goodbye. They may also babble a few words repeatedly and show that they understand simple commands.

Dental Development in the First Year

The deciduous (baby) teeth generally start to emerge around six months of age. The emergence of teeth is called teething. While the teeth are close to emerging through the gums, the gums may become red, swollen, and painful. The baby is likely to drool and be fussy during the few days it takes for the teeth to finally emerge. The baby might also refuse to eat or drink because of the discomfort. The two lower central incisors usually emerge first at about six months, followed by the two upper central incisors at about eight months. The four lateral incisors (two upper and two lower) emerge at roughly ten months.

Physical Growth in the First Year

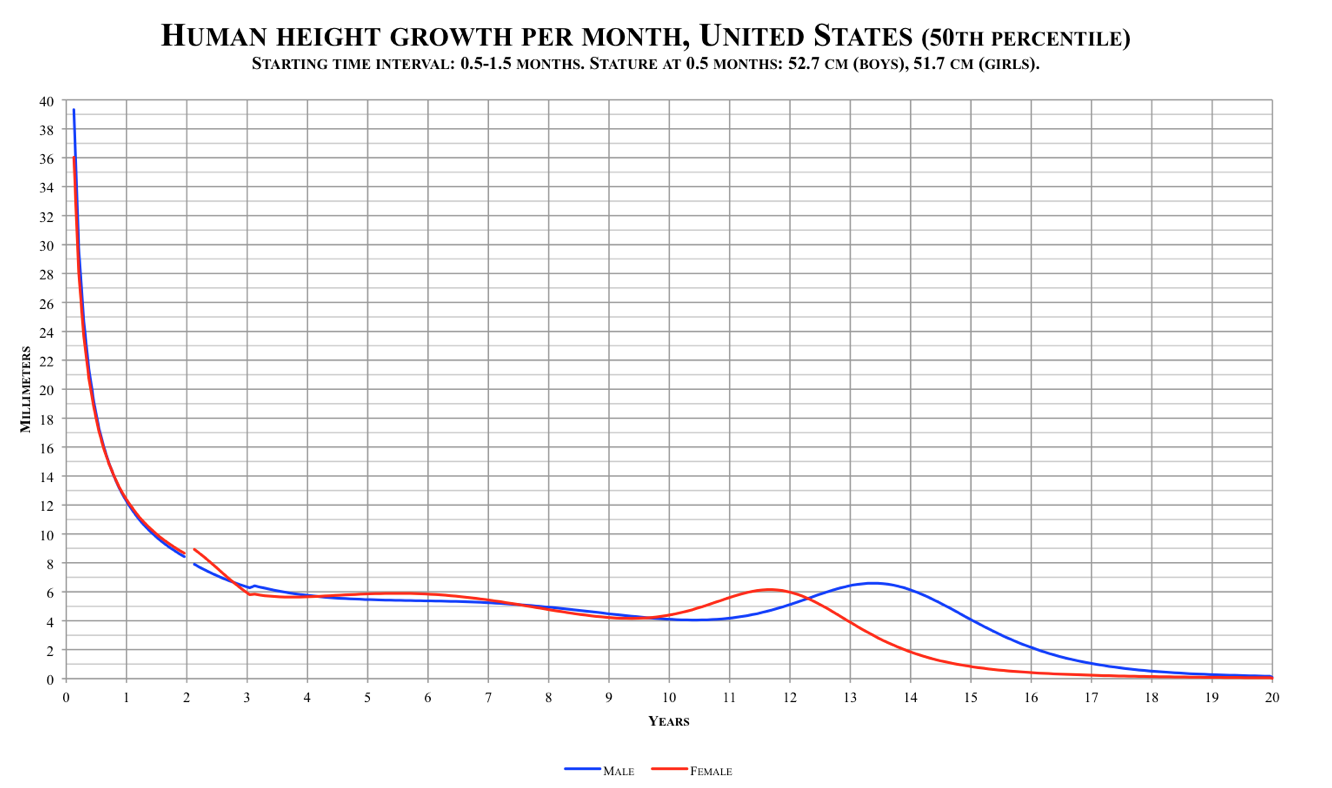

Infancy is the period of most rapid growth after birth. Growth during infancy is even faster than it is during puberty when the adolescent growth spurt occurs, as shown in the graph in Figure \(\PageIndex{12}\).

Growth in Weight and Length

Following the initial weight loss right after birth, an infant normally gains an average of about 28 g (1 oz) per day during the first two months. Then, weight gain slows somewhat, and the infant normally gains about 0.45 kg (1 lb) per month during the remainder of the first year. At this rate of weight gain, an infant generally doubles its birth weight by six months after birth and triples its birth weight by 12 months after birth.

Growth in overall body length is also very rapid during infancy, especially in the first few months. Infants normally grow about 2.5 cm (1.0 in.) per month during the first six months. During the second six months, they normally grow about 1.2 cm (0.5 in.) per month. At this rate of growth in length, an infant may close to double its birth length by the end of the first year!

During doctor visits throughout the first year of life, a baby’s weight and length are measured. The baby’s values are compared to standard weight and length values for infants of the same age to assess whether the baby is growing normally. The actual weight and length are generally considered to be less important than evidence showing that the baby is failing to grow normally between visits. Babies that grow too slowly may have a health problem or maybe undernourished. If this goes uncorrected, it can produce permanent deficits in size. On the other hand, a faster-than-normal increase in weight may result in the infant becoming too heavy and being at greater risk of obesity later in life.

Feature: Reliable Sources

Sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) is the unexplained death, usually during sleep, of a seemingly healthy infant. In the U.S., SIDS is one of the leading causes of death in the first year of life, with about two thousand infants dying in the U.S. each year from SIDS. The cause of SIDS is unknown, although scientists suspect that immaturity or abnormality of the part of the brain that controls arousal from sleep and breathing may be involved. Researchers have also identified several factors that increase the risk of SIDS. Some risks include male sex, pre-term birth, low birth weight, exposure to secondhand smoke, and sleeping on the stomach. Certain practices — such as placing an infant on its back to sleep and not using pillows or blankets in the crib — can help reduce the risk of SIDS.

Go online to learn more about SIDS. Find reliable sources that answer the following questions.

- What current research is being undertaken to better understand the cause of SIDS? What risk factors or areas of concern are being investigated?

- How can parents reduce the risk of SIDS in their infants? Which three reliable sources of information on SIDS would you recommend to new parents to raise their awareness of SIDS and how to reduce the risk of SIDS in their infants?

Review

- Define infancy, infant, and neonate.

- What is an Apgar test? When and why is it administered?

- Describe what happens to the umbilical cord after birth.

- What are some physical characteristics of a neonate?

- What are the average length and weight of a well-nourished, full-term newborn?

- Why do newborns typically lose some weight in the first week after birth?

- Describe newborn sensory abilities.

- Identify some of the reflexes that are present in newborn infants, and how they help the newborn survive.

- Identify a milestone in infant development that typically occurs by each of the ages below. In general, how does the timing of developmental milestones vary among infants at the ages of two months, four months, six months, ten months, and one year

- Outline dental development in the first year.

- Describe growth during infancy.

- Define the infant mortality rate, and explain its significance.

- A mother brings her six-month-old to visit the pediatrician. She is concerned that he does not weigh nearly as much as his cousin, who is the same age. What is one piece of information that the pediatrician would likely want to know in order to help assess whether the infant’s weight is a concern?

- A baby is born and a nurse immediately records the observations below. What is this baby’s APGAR score? Is this score considered normal? Explain your answer.

- Its skin is blue at the extremities, but the body is pink.

- Its heart rate is 98 beats per minute.

- Baby cries on stimulation.

- Baby has flexed arms and legs that resist extension.

- Baby has a strong, robust cry.

Explore More

Blood in the umbilical cord is a rich source of stem cells that could potentially cure diseases, but cord blood is usually disposed of after birth. Watch the video below to learn about a public cord blood banking program that stores donated cord blood so that these valuable stem cells can be used to save lives.

Attributions

- Baby sleeping by ULOVInteractive, Pixabay license

- Newborn crying by Evan-Amos, public domain via Wikimedia Commons

- Newborn by Bigroger27509, public domain via Wikimedia Commons

- Doorknippen navelstreng by Mech, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

- Male figures showing proportions in five ages by http://wellcomeimages.org/Wellcome, CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

- Skull at birth by Henry Gray, public domain via Wikimedia Commons

- Breastfeeding by capsulanudes via Pixabay license

- Child's hand by Tembinkosi Sikupela via Unsplash license

- Infant smiling, public domain via pxhere

- Baby crawling by Bualong Pata, public domain via Wikimedia Commons

- Learning to walk by Shaun MItchem, CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

- Human height growth per month by Cantus, CC0 via Wikimedia Commons

- Text adapted from Human Biology by CK-12 licensed CC BY-NC 3.0