53.8.1: Honeybee Navigation

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 74422

The domestic honeybee, Apis mellifera, is a colonial insect living in hives containing one queen — a fertile female, a few drones (males), and thousands of workers (infertile females). The workers are responsible for keeping the hive clean, building the wax combs of the hive, tending the young and, when they get older (and when their for gene gets turned on), and foraging for food - nectar and pollen.

ome 5–25% of the workers in the hive are scouts. Their job is to search for new sources of food for the other workers, the foragers, to harvest. While both scouts and foragers look alike, recent research suggests that they represent stable subpopulations with distinctive patterns of gene expression in their brains. (See Liang, Z. S., et al., in the 9 March 2012 issue of Science.)

When food is discovered by scouts, they return to the hive. Shortly after their return, many foragers leave the hive and fly directly to the food. The remarkable thing about this is that the foragers do not follow the scouts back. The scouts may remain in the hive for hours and those that leave continue to hunt for new sources of food even though the foragers are continuing to bring back ample supplies of food from the sites the scouts discovered earlier. So the scout bees have communicated to the foragers the necessary information for them to find the food on their own.

It turns out that the scouts can convey to the foragers information about

- the odor of the food

- its direction from the hive

- its distance from the hive

Distance

When food is within 50–75 meters of the hive, the scouts dance the "round dance" on the surface of the comb (left). But when the food is farther than 75 meters from the hive, the scouts dance the "waggle dance" (right). The waggle dance has two components: (1) a straight run - the direction of which conveys information about the direction of the food and (2) the speed at which the dance is repeated which indicates how far away the food is.

The graph shows the relationship between the speed of the dance and the distance to the food. It is based on data collected by the German ethologist Karl von Frisch. It was he who discovered much of what we know today about honeybee communication (and was honored with a Nobel Prize in 1973).

How do the bees calculate distance? von Frisch thought they measured the distance by assessing the amount of energy it took to get there. But the mechanism turns out to be quite different. The bees measure distance by the motion of images received by their eyes as they fly.

Flicker Effect

Honeybees, like all insects, have compound eyes. These give little information about depth but are very sensitive to "flicker effect". It has long been known to bee keepers that honeybees respond better to flowers

- moving in the breeze

- with complex petals

The importance of flicker effect can be demonstrated by training honeybees to visit food placed on cards with patterns. For example, the bees can distinguish any figure in the top row from any figure in the bottom row more easily than they can distinguish between any of the figures in either row.

Evidence of distance measuring

Working at the University of Notre Dame (Indiana), Esch and Burns found that when the hive and food were placed on top of tall (50 m) buildings, the speed of the waggle dance indicated a distance only half of the distance indicated by bees travelling the same distance (230 m) at ground level. Features of the scenery pass the retina faster when near than when far (compare the changes in your view from an airliner at cruising altitude and as it approaches the runway).

Tests of Searching Behavior

Working at the Australian National University, Srinivasan and his colleagues built tunnels decorating the interior walls with patterns to create flicker. In these three experiments, the bees were first fed in the middle of the tunnel of standard diameter. Then the food was removed.

- Using the same tunnel, foragers came to same spot in the tunnel.

- Using a narrower tunnel, foragers began searching for food near its entrance. Forced to fly closer to the vertical stripes, the images moved by faster.

- Using a tunnel with a larger diameter, foragers searched for food at its far end. Flying farther from the stripes, the images moved by more slowly.

Tests of Dancing Behavior

All tunnels were 6 meters long and located 35 meters from the hive — well within the distance (50–75 m) that normally elicits the round dance.

- Bees were fed at the entrance. Back at the hive, they danced the round dance as you would expect.

- Bees fed at end of tunnel. Back at the hive, they danced the waggle dance. Even though the total distance from the hive (41 m) was still well within the "round" range, the complexity of the scenery passed in the last 6 m, elicited the waggle dance.

- Bees fed at end of tunnel decorated with horizontal stripes. These created no flicker as the bees flew, and on their return to the hive they danced the round dance.

You can read about this second set of experiments in Srinivasan, et. al., Science, 4 February 2000.

Recruits respond to the misinformation given by returning scouts

More recently, the Esch and Srinivasan groups have teamed up to show that naive foragers are fooled by the misinformation that the returning scouts give them. When scouts were fed only 11 m from the hive but at the far end of a striped tunnel, they danced the waggle dance back at the hive as though the food had been 70 m away. Most of the workers they recruited flew out (bypassing the tunnel) 70 m looking for food. You can read about these experiments in Ungless, et. al., Nature, 31 May 2001.

Direction

By itself, the knowledge that food is 6 kilometers (3.7 miles) away is not very useful. But von Frisch also noted that the direction of the straight portion of the waggle dance varied with the direction of the food source from the hive and the time of day.

- At any one time, the direction changes with the location of the food.

- With a fixed source of food, the direction changes by the same angle as the sun during its passage through the sky.

But

- The sun is not visible within the hive.

- The scouts dance on the vertical surface of the combs.

How, then, do they translate flight angles in the darkened hive?

The picture shows the relationship between the angle of the dance on the vertical comb and the bearing of the sun with respect to the location of food. When the food and sun are in the same direction, the straight portion of the waggle dance is directed upward. When the food is at some angle to the right (blue) or left (red) of the sun, the bee orients the straight portion of her dance at the same angle to the right or left of the vertical.

Using radar to track individual bees recruited by the waggle dance, Riley, J. R., et al., (Nature, 12 May 2005) have shown that the recruits do fly in the indicated direction. They even adjust their flight path to compensate for being blown off course by the wind. However, their course is seldom so precise that they can find the food without the aid of vision and/or smell as they neared it.

Other features

Time Sense

When scouts remain in the hive for a long period, they shift the direction of the straight portion of the waggle dance as the day wears on (and the direction of the sun shifts). But they cannot see the sun in the darkened hive. Evidently, they are "aware" of the passing time and make the necessary corrections.

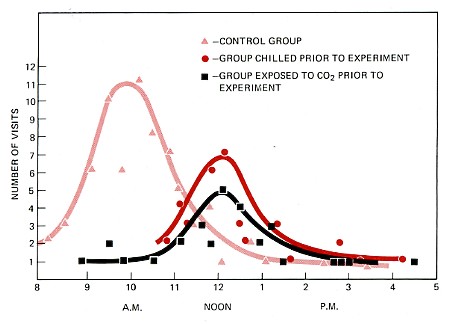

The time sense of honeybees has long been known to people who have sweet snacks in their garden at a set time every day. Within minutes of the regular time, foraging bees arrive for their share of the jam. The speed of the bee's clock seems to be related to its metabolic rate. If normally punctual bees are chilled (to lower their metabolic rate) or exposed to an anesthetizing concentration of carbon dioxide they arrive late to the picnic table (graph above).

Polarized light

von Frisch also discovered that scouts (and foragers) don't actually have to see the sun to navigate. As long as they can see a small patch of clear blue sky, they get along fine. This is because sky light is partially polarized, and the plane of polarization in any part of the sky is determined by the location of the sun. Try it by rotating a pair of polaroid® sun glasses!

Swarming

Before a new queen emerges, the old queen leaves the hive, taking many of the workers with her. The swarm usually settles somewhere, e.g., on a tree branch, while scouts go searching for a new home. Each scout that finds a promising site, returns to the swarm and dances on it just as though she had found food. Eventually, the swarm departs for the location promoted most vigorously. Once the new hive is established, many of the scouts that found the site will become food scouts.

Grooming

Workers have another type of dance — rapidly vibrating from side to side — that tells other workers that she needs help removing dust, pollen, etc. from hard-to-reach places on her body.