5.3: Active Transport

- Page ID

- 1847

Skills to Develop

- Understand how electrochemical gradients affect ions

- Distinguish between primary active transport and secondary active transport

Active transport mechanisms require the use of the cell’s energy, usually in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP). If a substance must move into the cell against its concentration gradient—that is, if the concentration of the substance inside the cell is greater than its concentration in the extracellular fluid (and vice versa)—the cell must use energy to move the substance. Some active transport mechanisms move small-molecular weight materials, such as ions, through the membrane. Other mechanisms transport much larger molecules.

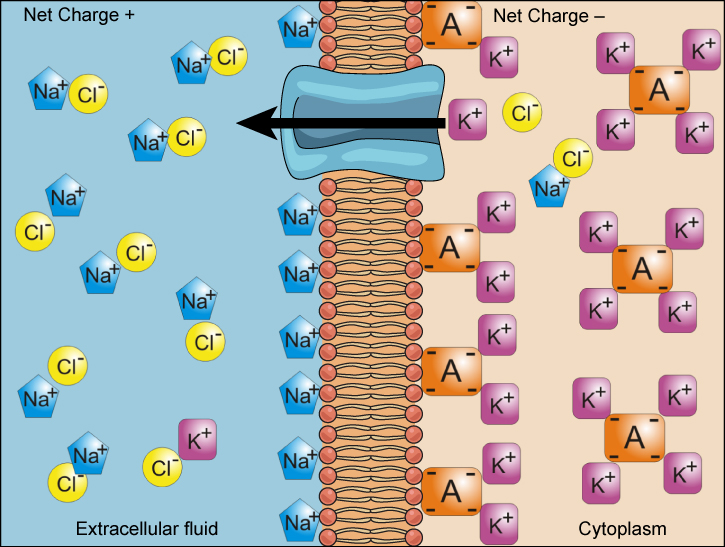

Electrochemical Gradient

We have discussed simple concentration gradients—differential concentrations of a substance across a space or a membrane—but in living systems, gradients are more complex. Because ions move into and out of cells and because cells contain proteins that do not move across the membrane and are mostly negatively charged, there is also an electrical gradient, a difference of charge, across the plasma membrane. The interior of living cells is electrically negative with respect to the extracellular fluid in which they are bathed, and at the same time, cells have higher concentrations of potassium (K+) and lower concentrations of sodium (Na+) than does the extracellular fluid. So in a living cell, the concentration gradient of Na+ tends to drive it into the cell, and the electrical gradient of Na+ (a positive ion) also tends to drive it inward to the negatively charged interior. The situation is more complex, however, for other elements such as potassium. The electrical gradient of K+, a positive ion, also tends to drive it into the cell, but the concentration gradient of K+ tends to drive K+ out of the cell (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). The combined gradient of concentration and electrical charge that affects an ion is called its electrochemical gradient.

Art Connection

Injection of a potassium solution into a person’s blood is lethal; this is used in capital punishment and euthanasia. Why do you think a potassium solution injection is lethal?

Moving Against a Gradient

To move substances against a concentration or electrochemical gradient, the cell must use energy. This energy is harvested from ATP generated through the cell’s metabolism. Active transport mechanisms, collectively called pumps, work against electrochemical gradients. Small substances constantly pass through plasma membranes. Active transport maintains concentrations of ions and other substances needed by living cells in the face of these passive movements. Much of a cell’s supply of metabolic energy may be spent maintaining these processes. (Most of a red blood cell’s metabolic energy is used to maintain the imbalance between exterior and interior sodium and potassium levels required by the cell.) Because active transport mechanisms depend on a cell’s metabolism for energy, they are sensitive to many metabolic poisons that interfere with the supply of ATP.

Two mechanisms exist for the transport of small-molecular weight material and small molecules. Primary active transport moves ions across a membrane and creates a difference in charge across that membrane, which is directly dependent on ATP. Secondary active transport describes the movement of material that is due to the electrochemical gradient established by primary active transport that does not directly require ATP.

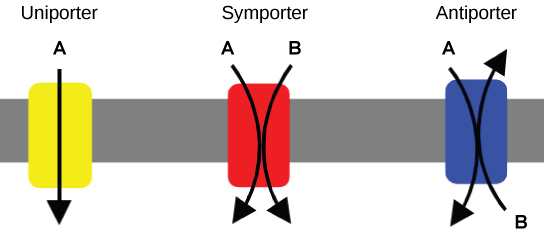

Carrier Proteins for Active Transport

An important membrane adaption for active transport is the presence of specific carrier proteins or pumps to facilitate movement: there are three types of these proteins or transporters (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)). A uniporter carries one specific ion or molecule. A symporter carries two different ions or molecules, both in the same direction. An antiporter also carries two different ions or molecules, but in different directions. All of these transporters can also transport small, uncharged organic molecules like glucose. These three types of carrier proteins are also found in facilitated diffusion, but they do not require ATP to work in that process. Some examples of pumps for active transport are Na+-K+ ATPase, which carries sodium and potassium ions, and H+-K+ ATPase, which carries hydrogen and potassium ions. Both of these are antiporter carrier proteins. Two other carrier proteins are Ca2+ ATPase and H+ ATPase, which carry only calcium and only hydrogen ions, respectively. Both are pumps.

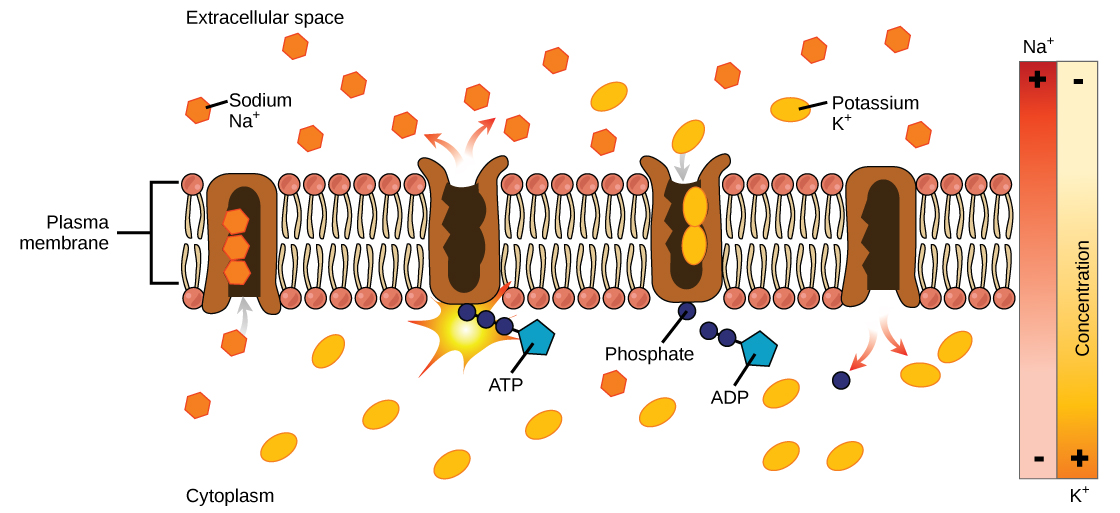

Primary Active Transport

The primary active transport that functions with the active transport of sodium and potassium allows secondary active transport to occur. The second transport method is still considered active because it depends on the use of energy as does primary transport (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)).

One of the most important pumps in animals cells is the sodium-potassium pump (Na+-K+ ATPase), which maintains the electrochemical gradient (and the correct concentrations of Na+ and K+) in living cells. The sodium-potassium pump moves K+ into the cell while moving Na+ out at the same time, at a ratio of three Na+ for every two K+ ions moved in. The Na+-K+ ATPase exists in two forms, depending on its orientation to the interior or exterior of the cell and its affinity for either sodium or potassium ions. The process consists of the following six steps.

- With the enzyme oriented towards the interior of the cell, the carrier has a high affinity for sodium ions. Three ions bind to the protein.

- ATP is hydrolyzed by the protein carrier and a low-energy phosphate group attaches to it.

- As a result, the carrier changes shape and re-orients itself towards the exterior of the membrane. The protein’s affinity for sodium decreases and the three sodium ions leave the carrier.

- The shape change increases the carrier’s affinity for potassium ions, and two such ions attach to the protein. Subsequently, the low-energy phosphate group detaches from the carrier.

- With the phosphate group removed and potassium ions attached, the carrier protein repositions itself towards the interior of the cell.

- The carrier protein, in its new configuration, has a decreased affinity for potassium, and the two ions are released into the cytoplasm. The protein now has a higher affinity for sodium ions, and the process starts again.

Several things have happened as a result of this process. At this point, there are more sodium ions outside of the cell than inside and more potassium ions inside than out. For every three ions of sodium that move out, two ions of potassium move in. This results in the interior being slightly more negative relative to the exterior. This difference in charge is important in creating the conditions necessary for the secondary process. The sodium-potassium pump is, therefore, an electrogenic pump (a pump that creates a charge imbalance), creating an electrical imbalance across the membrane and contributing to the membrane potential.

Link to Learning

Visit the site to see a simulation of active transport in a sodium-potassium ATPase.

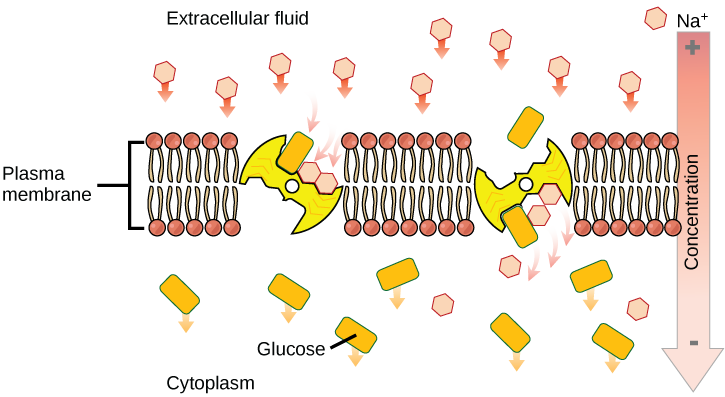

Secondary Active Transport (Co-transport)

Secondary active transport brings sodium ions, and possibly other compounds, into the cell. As sodium ion concentrations build outside of the plasma membrane because of the action of the primary active transport process, an electrochemical gradient is created. If a channel protein exists and is open, the sodium ions will be pulled through the membrane. This movement is used to transport other substances that can attach themselves to the transport protein through the membrane (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)). Many amino acids, as well as glucose, enter a cell this way. This secondary process is also used to store high-energy hydrogen ions in the mitochondria of plant and animal cells for the production of ATP. The potential energy that accumulates in the stored hydrogen ions is translated into kinetic energy as the ions surge through the channel protein ATP synthase, and that energy is used to convert ADP into ATP.

Art Connection

If the pH outside the cell decreases, would you expect the amount of amino acids transported into the cell to increase or decrease?

Summary

The combined gradient that affects an ion includes its concentration gradient and its electrical gradient. A positive ion, for example, might tend to diffuse into a new area, down its concentration gradient, but if it is diffusing into an area of net positive charge, its diffusion will be hampered by its electrical gradient. When dealing with ions in aqueous solutions, a combination of the electrochemical and concentration gradients, rather than just the concentration gradient alone, must be considered. Living cells need certain substances that exist inside the cell in concentrations greater than they exist in the extracellular space. Moving substances up their electrochemical gradients requires energy from the cell. Active transport uses energy stored in ATP to fuel this transport. Active transport of small molecular-sized materials uses integral proteins in the cell membrane to move the materials: These proteins are analogous to pumps. Some pumps, which carry out primary active transport, couple directly with ATP to drive their action. In co-transport (or secondary active transport), energy from primary transport can be used to move another substance into the cell and up its concentration gradient.

Art Connections

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Injection of a potassium solution into a person’s blood is lethal; this is used in capital punishment and euthanasia. Why do you think a potassium solution injection is lethal?

- Answer

-

Cells typically have a high concentration of potassium in the cytoplasm and are bathed in a high concentration of sodium. Injection of potassium dissipates this electrochemical gradient. In heart muscle, the sodium/potassium potential is responsible for transmitting the signal that causes the muscle to contract. When this potential is dissipated, the signal can’t be transmitted, and the heart stops beating. Potassium injections are also used to stop the heart from beating during surgery.

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\): If the pH outside the cell decreases, would you expect the amount of amino acids transported into the cell to increase or decrease?

- Answer

-

A decrease in pH means an increase in positively charged H+ ions, and an increase in the electrical gradient across the membrane. The transport of amino acids into the cell will increase.

Glossary

- active transport

- method of transporting material that requires energy

- antiporter

- transporter that carries two ions or small molecules in different directions

- electrochemical gradient

- gradient produced by the combined forces of an electrical gradient and a chemical gradient

- electrogenic pump

- pump that creates a charge imbalance

- primary active transport

- active transport that moves ions or small molecules across a membrane and may create a difference in charge across that membrane

- pump

- active transport mechanism that works against electrochemical gradients

- secondary active transport

- movement of material that is due to the electrochemical gradient established by primary active transport

- symporter

- transporter that carries two different ions or small molecules, both in the same direction

- transporter

- specific carrier proteins or pumps that facilitate movement

- uniporter

- transporter that carries one specific ion or molecule