6.2: DNA and RNA

- Page ID

- 16747

This person has naturally red hair. Why is this hair red instead of some other color? And, in general, what causes specific traits to occur? There is a molecule in human beings and most other living things that is largely responsible for their traits. The molecule is large and has a spiral structure in eukaryotes. What molecule is it? With these hints, you probably know that the molecule is DNA.

Introducing DNA

Today, it is commonly known that DNA is the genetic material that is passed from parents to offspring and determines our traits. For a long time, scientists knew such molecules existed, that is, they were aware that genetic information is contained within biochemical molecules. However, they didn’t know which molecules play this role. In fact, for many decades, scientists thought that proteins were the molecules that contain genetic information.

Discovery that DNA is the Genetic Material

Determining that DNA is the genetic material was an important milestone in biology. It took many scientists undertaking creative experiments over several decades to show with certainty that DNA is the molecule that determines the traits of organisms. This research began in the early part of the 20th century.

Griffith's Experiments with Mice

The first important discovery was made in the 1920s. An American scientist named Frederick Griffith was studying mice and two different strains of a bacterium called R (rough) strain and S (smooth) strain. He injected the two bacterial strains into mice. The S strain was virulent and killed the mice, whereas the R strain was not virulent and did not kill the mice. You can see these details in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\). Griffith also injected mice with S-strain bacteria that had been killed by heat. As expected, the dead bacteria did not harm the mice. However, when the dead S-strain bacteria were mixed with live R-strain bacteria and injected, the mice died.

Based on his observations, Griffith deduced that something in the dead S-strain was transferred to the previously harmless R-strain, making the R-strain deadly. What was this "something?" What type of substance could change the characteristics of the organism that received it?

Avery and His Colleagues Make a Major Contribution

In the early 1940s, a team of scientists led by Oswald Avery tried to answer the question raised by Griffith’s research results. First, they inactivated various substances in the S-strain bacteria. Then they killed the S-strain bacteria and mixed the remains with live R-strain bacteria. (Keep in mind that the R-strain bacteria normally did not harm the mice.) When they inactivated proteins, the R-strain was deadly to the injected mice. This ruled out proteins as genetic material. Why? Even without the S-strain proteins, the R-strain was changed or transformed into a deadly strain. However, when the researchers inactivated DNA in the S-strain, the R-strain remained harmless. This led to the conclusion that DNA — and not protein — is the substance that controls the characteristics of organisms. In other words, DNA is the genetic material.

Hershey and Chase Confirm the Results

The conclusion that DNA is the genetic material was not widely accepted until it was confirmed by additional research. In the 1950s, Alfred Hershey and Martha Chase did experiments with viruses and bacteria. Viruses are not cells. Instead, they are basically DNA (or RNA) inside a protein coat. To reproduce, a virus must insert its own genetic material into a cell (such as a bacterium). Then it uses the cell’s machinery to make more viruses. The researchers used different radioactive elements to label the DNA and proteins in DNA viruses. This allowed them to identify which molecule the viruses inserted into bacterial cells. DNA was the molecule they identified. This confirmed that DNA is the genetic material.

Chargaff Focuses on DNA Bases

Erwin Chargaff (1905-2002), an Austrian-American biochemist from Columbia University, analyzed the base composition of the DNA of various species. This led him to propose two main rules that have been appropriately named Chargaff's rules.

Rule 1

Chargaff determined that in DNA, the amount of one base, a purine, always approximately equals the amount of a particular second base, a pyrimidine. Specifically, in any double-stranded DNA, the number of guanine units equals approximately the number of cytosine units and the number of adenine units equals approximately the number of thymine units.

Human DNA is 30.9% A and 29.4% T, 19.9% G and 19.8% C. The rule constitutes the basis of base pairs in the DNA double helix: A always pairs with T, and G always pairs with C. He also demonstrated that the number of purines (A+G) always approximates the number of pyrimidines (T+C), an obvious consequence of the base-pairing nature of the DNA double helix.

Rule 2

In 1947 Chargaff showed that the composition of DNA, in terms of the relative amounts of the A, C, G, and T bases, varied from one species to another. This molecular diversity added to the evidence that DNA could be the genetic material.

Discovery of the Double Helix

After DNA was shown to be the genetic material, scientists wanted to learn more about it, including its structure. James Watson and Francis Crick are usually given credit for discovering that DNA has a double-helix shape like a spiral staircase, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\). In fact, Watson and Crick's discovery of the double helix depended heavily on the prior work of Rosalind Franklin and other scientists, who had used X-rays to learn more about DNA’s structure. Unfortunately, Franklin and these other scientists have not usually been given credit for their important contributions to the discovery of the double helix.

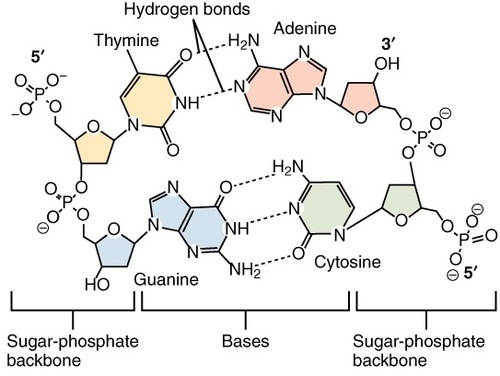

The double-helix shape of DNA, together with Chargaff’s rules, led to a better understanding of DNA. As a nucleic acid, DNA is made from nucleotide monomers. Long chains of nucleotides form polynucleotides, and the DNA double helix consists of two polynucleotide chains. Each nucleotide consists of a sugar (deoxyribose), a phosphate group, and one of the four bases (adenine, cytosine, guanine, or thymine). The sugar and phosphate molecules in adjacent nucleotides bond together and form the "backbone" of each polynucleotide chain.

Scientists concluded that bonds between the bases hold together the two polynucleotide chains of DNA. Moreover, adenine always bonds with thymine, and cytosine always bonds with guanine. That's why these pairs of bases are called complementary base pairs. If you look at the nitrogen bases in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\), you will see why the bases bond together only in these pairings. Adenine and guanine have a two-ring structure, whereas cytosine and thymine have just one ring. If adenine were to bond with guanine as well as thymine, for example, the distance between the two DNA chains would be variable. However, when a one-ring molecule (such as thymine) always bonds with a two-ring molecule (such as adenine), the distance between the two chains remains constant. This maintains the uniform shape of the DNA double helix. The bonded base pairs (A-T and G-C) stick into the middle of the double helix, forming, in essence, the steps of the spiral staircase.

DNA Replication

Knowledge of DNA’s structure helped scientists understand how DNA replicates. DNA replication is the process in which DNA is copied. It occurs during the synthesis (S) phase of the eukaryotic cell cycle. DNA must be copied so that, after cell division occurs, each daughter cell will have a complete set of chromosomes.

DNA replication begins when an enzyme breaks the bonds between complementary bases in the molecule. This exposes the bases inside the molecule so they can be “read” by another enzyme and used to build two new DNA strands with complementary bases. The two daughter molecules that result each contain one strand from the parent molecule and one new strand that is complementary to it. As a result, the two daughter molecules are both identical to the parent molecule. This is a semi-conservative process (see Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\).)

Helicase and Polymerase

DNA replication begins as an enzyme, DNA helicase, breaks the hydrogen bonds holding the two strands together and forms a replication fork (see Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\). The resulting structure has two branching strands of DNA backbone with exposed bases. These exposed bases allow the DNA to be “read” by another enzyme, DNA polymerase, which then builds the complementary DNA strand. As DNA helicase continues to open the double helix, the replication fork grows.

Leading and Lagging Strands

Two DNA polymerase enzymes work at a Replication fork. This enzyme can only build new DNA in the 5' → 3' direction. It also needs a primer built by primase to start building DNA. Therefore, the two new strands, the leading strand and the lagging strand, of DNA are “built” in opposite directions. The leading strand is the DNA strand that DNA polymerase constructs in the 5' → 3' direction. This strand of DNA is made in a continuous manner, moving as the replication fork grows. The "lagging” strand is synthesized in short segments known as Okazaki fragments. On the lagging strand, primase builds a short RNA primer. DNA polymerase is then able to use the free 3'-OH group on the RNA primer to make DNA in the 5' → 3' direction till it reaches to end of the template strand. DNA polymerase of the lagging strand then jumps to go further into the replication fork to make another Okazaki fragment. The RNA fragments are then degraded and new DNA nucleotides are added to fill the gaps where the RNA was present. Another enzyme, DNA ligase, is then able to attach (ligate) the DNA nucleotides together, completing the synthesis of the lagging strand (Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\)).

What is RNA?

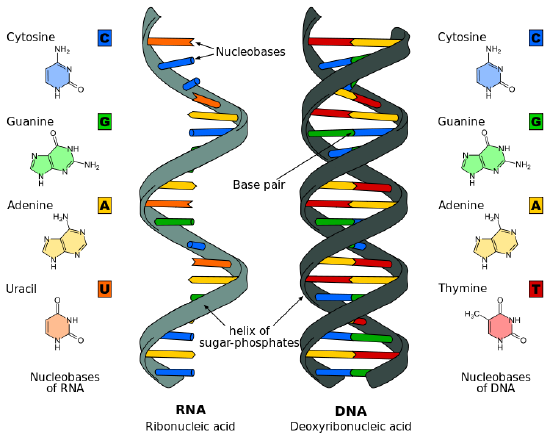

RNA structure differs from the DNA structure in three specific ways. Both are nucleic acids and made out of nucleotides; however, RNA is single-stranded while DNA is double-stranded. RNA nucleotides, like those from DNA, have three parts: a 5-carbon sugar, a phosphate group, and a base. RNA contains the 5-carbon sugar ribose, whereas, in DNA, the sugar is deoxyribose. The difference between ribose and deoxyribose is the lack of a hydroxyl group attached to the pentose ring in the 2' position of deoxyribose (see figure Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\).

| RNA | DNA | |

|---|---|---|

| Strands | single stranded | double stranded |

| Specific Base | contains uracil | contains thymine |

| Sugar | ribose | deoxyribose |

| Size | relatively small | big (chromosomes) |

| Location | moves to cytoplasm | stays in nucleus |

| Types | 3 types: mRNA, tRNA, rRNA | generally 1 type |

Though both RNA and DNA contain the nitrogenous bases adenine, guanine, and cytosine, RNA contains the nitrogenous base uracil instead of thymine. Uracil pairs with adenine in RNA, just as thymine pairs with adenine in DNA. Uracil and thymine have very similar structures; uracil is an unmethylated form of thymine.

The nucleotide sequence of RNA, which is complementary to the DNA sequence, allows RNA to encode genetic information. RNA though carries the genetic information of just one gene. Hence, compared to DNA, RNA molecules are relatively small.

Review

- Outline the discoveries that led to the determination that DNA, and not protein, is the biochemical molecule that contains genetic information.

- State Chargaff's rules. Explain how the rules are related to the structure of the DNA molecule.

- Explain how the structure of a DNA molecule is like a spiral staircase. Which parts of the staircase represent the various parts of the molecule?

- Describe the process of DNA replication.

- When does DNA replication occur, and why is the process said to be semi-conservative?

- Why do you think dead S strain bacteria injected into mice does not harm the mice but kills them when mixed with living (and normally harmless) R strain bacteria?

- In Griffith’s experiment, do you think the heat treatment that killed the bacteria also inactivated the bacterial DNA? Why or why not?

- Give one example of a specific piece of evidence that helped rule out proteins as the genetic material.

- True or False. Two-ring bases always bind to each other.

- True or False. DNA replication involves the breaking of one of the polynucleotide chains into individual nucleotides.

- True or False. In DNA, each nucleotide has a sugar.

- What would the complementary strand of this stretch of DNA bases be? GTTAC

- Which scientists detected labeled DNA that was transferred from one organism to another?

- Hershey and Chase

- Chargaff

- Avery

- Griffith

- Which enzyme break the bonds between complementary bases and add new complementary nucleotides to the parental strands during DNA replication?

- Phosphates

- Enzymes

- Viruses

- RNA molecules

- Describe the differences between DNA and RNA.

- How is DNA replicated? Why is DNA replication called a "semi-conservative" process?

- What are the roles of the following enzymes?

- DNA polymerase

- DNA helicase

- DNA ligase

- primase

Explore More

Rosalind Franklin was a British scientist who helped discover the structure of DNA. To learn more, check this out:

Attributions

- Rood by Zoë Cleeren, public domain via Wikimedia Commons

- Griffith experiment by Madprime, dedicated CC0 via Wikimedia Commons

- DNA Nucleotide by OpenStax College, licensed CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

- DNA structure and bases by MesserWoland, licensed CC BY-SA .30 via Wikimedia Commons

- DNA replication by Madprime, dedicated CC0 via Wikimedia Commons

- DNA replication by LadyofHats Mariana Ruiz, released into the public domain via Wikimedia Commons

- Difference DNA and RNA by Roland1952 licensed CC BY-SA .30 via Wikimedia Commons

- Text adapted from Human Biology by CK-12 licensed CC BY-NC 3.0