2.2: Introduction to Seed Germination

- Page ID

- 93150

By the end of this section you will be able to:

- Describe the differences between epigeal and hypogeal seedling emergence.

- Understand the terms that are used to describe different parts of the seedling as it emerges.

Seeds and their importance

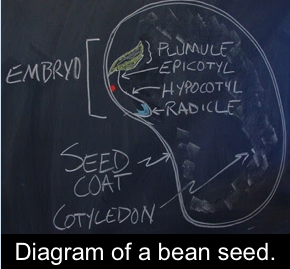

A seed, in botanical terms, is an embryonic plant enclosed inside its seed coat. Typically, the seed also has stored energy (proteins and carbohydrates) that are used by the seed during germination to establish itself when environmental conditions are favorable for growth. The stored energy is what makes seeds valuable for humans, too. Seeds are important in our daily lives because they feed us (food), feed livestock (aka, feed), and provide us with fuel and fiber for personal, home, and industrial purposes.

Seeds are by far the most common mode by which plants reproduce, and most people are familiar with their role in plant propagation and reproduction. The evolutionary advantage of reproduction by seed is the mixing of genetic material through meiotic recombination and the transfer of gametes (pollen) from one parent to another. This mixing of male and female parent genetics results in seeds, and thus seedlings, that are unique from one another and from the parents. The seeds may be dispersed locally or distributed far away through many mechanisms, such as wind, animals, insects, and water. Seedlings will germinate and grow, and those that are most fit in the environment will reproduce and pass on their genes to the next generation. This ability of plants to adapt to local environments and to pass on their genes is evolution in action, as new variations and even new species emerge and disappear from the landscape.

One advantage of seed production is that plants generally produce copious amounts of seed. Each seed may have slightly different germination requirements, a reflection of the diversity resulting from sexual recombination and an evolutionary strategy that allows seeds to germinate at different times. Seeds are able to remain dormant until the conditions are suitable for plant growth and survival, and have mechanisms that prevent germination before winter, during droughts, or in low-light environments. Some weedy species are excellent at interpreting these signals and may lie dormant for years in the soil “seed bank,” only germinating when the seed has been exposed.

Seedling emergence

Most seeds have a very slow metabolism when they are mature, which puts them in a state of quiescence: alive, but not growing and not physiologically active. At germination, the seed’s metabolic pathways are activated, leading to embryo growth and emergence of a new seedling. Germination begins with activation by water uptake. We call this imbibition, and sometimes the seed or fruit requires special treatment for water to get into the seed and start this process. We often use the emergence of the radicle (the embryonic root) from the seed coat as a measure of successful germination. Water uptake alone is not an indication that the seed is alive and growing, despite the expansion of seed tissues.

Cell division is taking place in the epicotyl, and the hypocotyl and the shoot and root are beginning to break through the seed coat. The new plant is beginning to grow and emerge from the soil.

Two types of seedling emergence

Epigeal and hypogeal

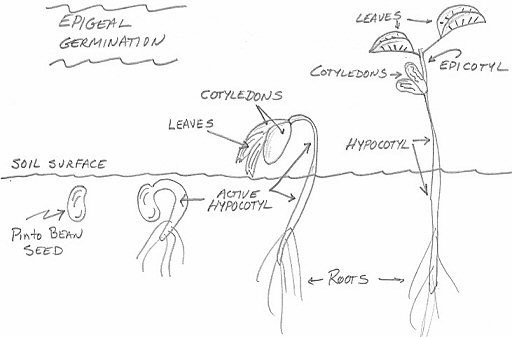

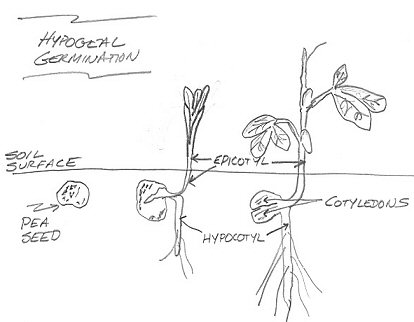

Epigeal and hypogeal are terms used to describe the position of the cotyledonary node during germination, indicating whether the node is above or below ground once the seedling has become established.

Epi means above while Hypo means below. The location of the cotyledonary node following seedling emergence is a characteristic used as a first step to differentiate plant species. The position of the cotyledon is affected by the rapidity of cell division in the hypocotyl region of the plant during germination and early seedling growth. The epicotyl is the embryonic shoot region above the attachment point of the cotyledons, and the hypocotyl the embryonic region below the cotyledon attachment point and extending down to where the root begins.

Epigeal

In this type of seedling emergence, cell division in the hypocotyl is initially more active and rapid than cell division in epicotyl. The actively dividing meristem in the hypocotyl causes cell growth and elongation that pushes some of the hypocotyl, as well as the cotyledonary node and epicotyl, above the soil surface. The cotyledonary node is above the ground — epigeal. The drawing shows four stages in the emergence of a pinto bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) which exhibits epigeal germination.

This video shows germination of a bean seed over a 10-day time span.

Hypogeal

In this type of seedling emergence, the apical meristem at the tip of the epicotyl is more active than the hypocotyl. This cell division and elongation pushes the epicotyl above the soil while the cotyledons and all of the hypocotyl remain below the soil surface. The cotyledonary node is below the ground — it is hypogeal. The example above is a pea (Pisum sativum L.) which exhibits hypogeal germination.

This video shows hypogeal germination of pea, where the cotyledonary node stays below the soil, and this video shows epigeal germination of bean, where the cotyledonary node is pushed above the soil.

- Does “epi” mean above or below? Above or below what?

- Diagram the seedling with the following: hypocotyl, cotyledons, epicotyl, and leaves.