1.3: Plant Parts we Eat

- Page ID

- 93146

By the end of this lesson you will be able to:

- Summarize the various above- and below-ground plant parts that contribute to your diet.

- Use the correct language of biology when identifying parts of plants.

- Appreciate the diversity of edible plant parts.

Above-ground plant parts we eat

Edible leaves and petioles

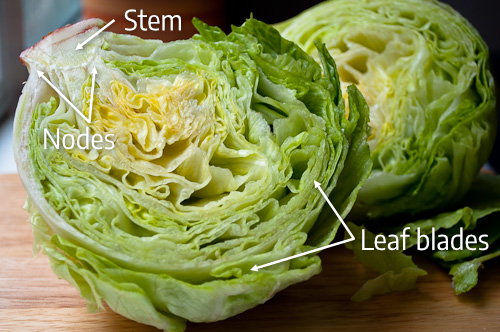

In this image of an iceberg lettuce cut in half, you can see how the leaf blades are packed and folded together tightly in the lettuce head. Lettuce is an example of a plant shoot with very short internodes on the stem. This results in a compact but leafy plant. Iceberg lettuce is a type of heading lettuce where older leaves envelop newer leaves forming a solid or semi-solid ball or head of lettuce leaves.

Romaine and leaf lettuces exhibit a more open architecture, with the leaves forming a looser head with upright leaves. Romaine lettuce has elongated leaves. There may be some tendency of older leaves to enclose newer leaves, but it is much less pronounced than in iceberg lettuce, and may be absent altogether in some of the garden types. Leaf lettuce lacks the tendency to form heads.

Lettuce leaves generally lack a petiole. The blade narrows a bit, but attaches directly to the node. A leaf lacking a petiole is called a “sessile” leaf. The point of attachment of the leaf to the stem is at a node. If you tear the leaves from a lettuce plant you are left with a short stem made up of many nodes and short internodes.

You can see in the romaine lettuce that its morphology is similar to that of the iceberg lettuce and that it has some tendency to wrap newer leaves within older. However, the nodes are a bit longer than what you see in iceberg lettuce, and that makes the node locations more apparent.

A few examples of leaf parts we eat

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://open.lib.umn.edu/horticulture/?p=105#h5p-6

Watch this video on edible leaves and petioles:

Modified petioles

Celery is an example of a leaf with a petiole. The parts that you eat are the petioles, while the leaf blades are often not present in the bunch of celery you purchase. If you buy a bunch of celery and pull off the large, outside petioles, inside you will find shorter petioles with the leaf blades still attached.

Celery is a geophyte (covered in a later lesson). Some of the celery petiole — the pale part at the bottom where it attaches to a node on the stem — grows underground. This part is pale because it lacks chlorophyll; the petioles were not exposed to sunlight and chlorophyll failed to develop.

Intentionally covering the petioles to discourage chlorophyll and encourage white, tender stems is called blanching. Blanched celery is more attractive to some cooks and consumers, although it may not be as nutritious.

An interactive H5P element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here:

https://open.lib.umn.edu/horticulture/?p=105#h5p-7

Edible stems

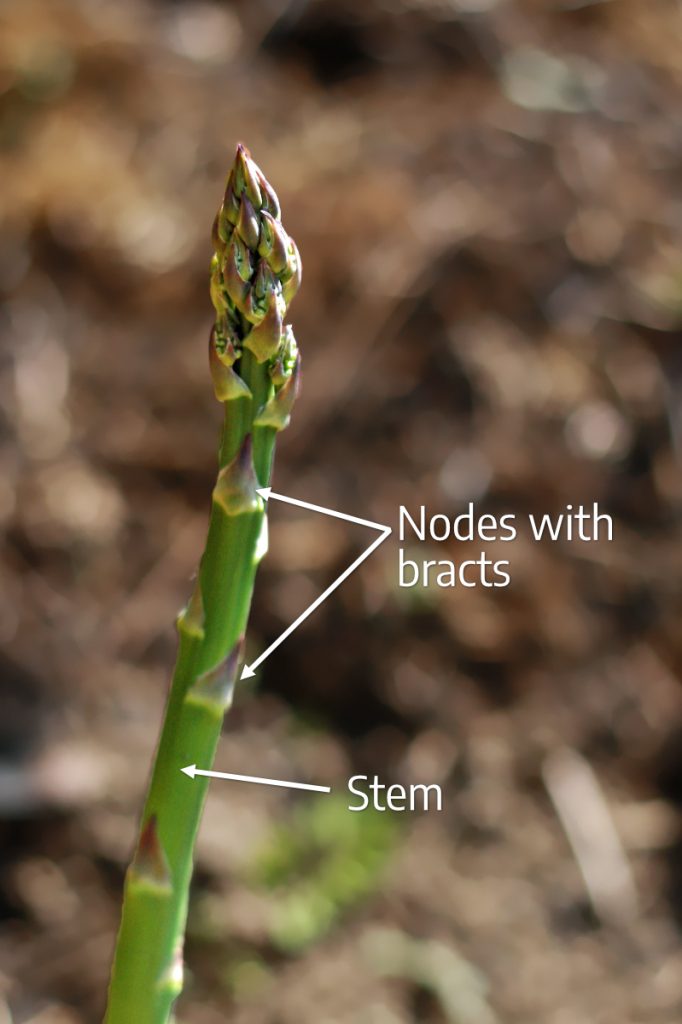

The photo below shows an asparagus shoot. You can tell it is a shoot by the regular node/internode construction of the stem. Most of the shoot is stem tissue. The triangular growth at each node is colloquially called a “bract” by asparagus growers, but it is actually a very small, scale-like leaf. If the shoots are left unharvested, branches grow from the nodes and then repeatedly branch into soft, feathery green foliage, as shown in the next photo.

Edible inflorescences

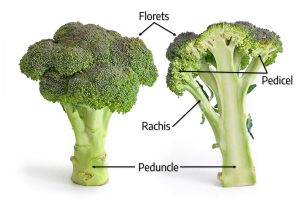

Broccoli and cauliflower are eaten as immature inflorescences. The dark green exterior of the broccoli inflorescence is made up of tight flower (or floret) buds that have not yet opened. The term “floret” is often used for the name of a flower born on a complex inflorescence.

Inside the inflorescence, the flower buds are supported by short, thin pedicels. The pedicel is attached to a series of increasingly thick internal stalks which make up the rachis structure of the inflorescence. The rachi all connect to the main stem of the inflorescence, which is the peduncle, and which then attaches to a node on the stem. The peduncle is the bit of the stalk that extends from the node where the inflorescence is attached to where the first rachis branches off. Above that, the central axis of the inflorescence is also called the rachis. An inflorescence can contain many rachi.

These plant parts may look similar, but they’re in different positions in the inflorescence. The terminology is important for distinguishing between parts, making observations, and describing different aspects of the plant, especially for data collection in experiments.

Nasturtiums, shown above, are also an inflorescence. They can be used as a colorful addition to a salad, and have a pleasant spicy flavor. In this case we are eating a single open flower, instead of a mass of immature rachi, pedicels, and florets as we are with broccoli.

It’s important to remember that not all flowers are edible, and some are even poisonous. If you’re interested in edible flowers, you must learn which species are safe to eat and how to identify and prepare them.

Cauliflower has very tight flower clusters, but otherwise has a very similar morphology to broccoli. Can you identify the pedicel, rachis, peduncle, and florets?

This Chinese cabbage has a morphology similar to that of romaine lettuce. Can you identify the stem, nodes, and leaf blades?

Fruits

We will deal with fruits in detail later in the course. Just a bit of introductory information: a fruit is a mature ovary that was part of a flower

Sometimes the botanical and culinary definitions conflict with one another. Botanically speaking, for instance, a nut is a fruit, as are a corn kernel, a pumpkin, a tomato, and an orange. As we’ll discuss, you could make a botanical argument that an apple isn’t a true fruit because the juicy part we eat isn’t ovary tissue; the ovary tissue is the core that we throw in the compost.

Below-ground plant parts we eat: Geophytes

Geophytes are plants with underground organs where the plant stores energy or water. Geophytes are often called bulbs, but they are far more diverse than that. Many of these plants protect buds using structures other than bulbs, such as rhizomes or enlarged roots. These modified parts include:

- Bulbs

- Tubers

- Rhizomes

- Roots, including storage and enlarged tap roots

Underground shoots

Bulb – onion

A bulb is a specialized, underground organ with a short, fleshy basal stem enclosed by thick, fleshy scales modified for storage. A true bulb consists of both leaf and stem tissue. The compressed stem, or basal plate, has attached to it a set of modified leaves called scales. These scales serve as the primary storage tissue for carbohydrates, nutrients, and water.

The main stem and apical meristem are protected by the layers of leaves. Axillary buds are born at the junction of the scale and basal plate (leaf and stem). Bulbs with a papery outer covering, like onions, are called tunicated. Plants that produce bulbs without this covering, like lilies, are non-tunicated.

Underground stems

Tuber – potato

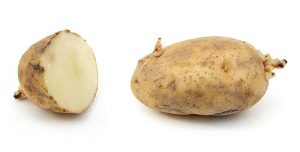

A tuber is a thickened, enlarged underground stem typically produced from a swelling of a stolon or rhizome. The stem tissue serves as the primary storage tissue for carbohydrates, nutrients, and water. The potato tuber is a typical example. Potato tubers are born on stolons that emerge from nodes near the soil surface.

It is common garden and agricultural practice to “hill” potatoes (mound loose soil around the base of the main stem of the plant) so the stolon grows into the mound of soil, where the tip swells into a tuber. Unlike a corm, which is also stem tissue, a tuber has no basal plate, but rather is fleshy throughout. The “eyes” of the potato are the meristems or buds from which new, above-ground growth initiates when conditions are favorable. These eyes are found at nodes on the tuber, which indicates that the tuber is shoot tissue rather than root.

Rhizome – ginger

Rhizomes are horizontal-growing underground stems that arise from nodes at or below the soil surface. In plants with fleshy rhizomes, these underground stems store nutrients and swell a bit. The stems are not usually as enlarged as a potato tuber, and the node/internode structure typical of stems is usually more obvious than on a potato. The stem tissue itself is the primary storage tissue, and it grows horizontally in the soil.

Ginger “root” (shown at right) isn’t really a root; it’s a rhizome (modified stem). The nodes and internodes, — found on stems, but not roots — are clearly visible.

Modified roots

Storage roots – sweet potato

Storage roots are enlarged fleshy portions of root tissue, and are are the primary storage tissue. There may be a bit of stem — the crown — attached to these roots, where you will find the buds from which new above-ground growth will initiate.

In plants with storage and fleshy roots, including dahlias and daylilies, it is important to protect the buds on the crown of the root because new shoots originate from there. Roots of some plants can produce shoots directly from the root tissue, Sweet potatoes are propagated this way; roots are cut, new shoots emerge from the cut roots, and these shoots are transplanted into the sweet potato field. Not all plants can produce new shoots from roots.

Tap root – radish, carrot, parsnip, beet, turnip

The swollen primary root is the storage organ. New growth initiates from buds at the crown, which is a small area of stem tissue sitting atop the tap root.

Hypocotyl – radish

The below-ground organ of the Raphinus sativa (radish) is not a root or shoot, but the continued growth of the hypocotyl — the part of the embryo arising from the cotyledonary node (where the cotyledons attach to the beginning of the root), and evident when a seed germinates.

- Compare and contrast a tuber and a storage root. Which one is actually stem tissue?

- If ginger isn’t a root, what is it and how can you tell?

- What part of rhubarb and celery do we eat?