28.15: Signaling in Microorganisms

- Page ID

- 79684

The main organization of this section derives from Bacterial transmembrane signaling systems and their engineering for biosensing. Jung et al :25 April 2018https://doi.org/10.1098/rsob.180023. Creative Commons Attribution License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Significant content from the source has been integrated into the section.

Introduction

Bacteria constantly interact with their surroundings. They identify and actively acquire nutrient resources, sense and respond to environmental stresses, and exchange information with other cells, while commensals and pathogens adapt their lifestyles for survival in their hosts. The cytoplasmic (inner) membrane of bacterial cells separates the cytoplasm from the outer world. Therefore, all information from the outside must be transferred across this interface, which contains various sensors that carry out this function.

Bacteria use three major types of signaling systems: membrane-integrated one-component systems (for example -ToxR-like receptors), two-component systems consisting of a receptor histidine kinase and a response regulator, and extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors. These are shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\).

The one-component signaling family ToxR (named after the main regulator of virulence in Vibrio cholerae) is the simplest. They have a periplasmic sensor domain, a single transmembrane helix, and an intracellular winged helix-turn-helix DNA-binding domain. The family is named after the main regulator of virulence in Vibrio cholerae, ToxR.

In two-component systems, the membrane-integrated histidine kinase generally acts as a sensor for various stimuli and is also responsible for information transfer across the membrane. This process usually results in the autophosphorylation of the protein and the phosphoryl group is subsequently transferred to a specific soluble response regulator which usually acts as a transcription factor (see Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). The number of histidine kinase/response regulator systems varies widely between bacterial species, ranging from 30 in Escherichia coli and 36 in Bacillus subtilis to 132 in Myxococcus xanthus. In chemotactic systems, a soluble histidine kinase perceives the signal(s) conveyed by membrane-integrated chemoreceptors and transduces this information via phosphorylation/protein–proteins interaction to the flagellar motor.

The ECF sigma factors are small regulatory proteins that bind to RNA polymerase and stimulate the transcription of specific genes. Many bacteria, particularly those with more complex genomes, contain multiple ECF sigma factors, and these regulators often outnumber all other types of sigma factors. Little is known about the roles or the regulatory mechanisms employed by the majority of ECF sigma factors. Most of them are co-expressed with one or more negative regulators. Often, these regulators include a transmembrane protein that functions as an anti-sigma factor, which binds and inhibits the cognate sigma factor.

Let's look at three examples.

One-component system: pH sensor CadC

pH in E. Coli is regulated by a series of Cad proteins. CadA is a cytoplasmic decarboxylase, which converts lysine to cadaverine, while CadB is a membrane-integrated lysine/cadaverine antiporter. CadC acts as a homodimeric one-component regulator. Together, their activities lead to an increase in both internal and external pH, which favors the survival of E. coli under moderate acid stress and helps to maintain pH homeostasis. Their activities are shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\).

CadC is the regulator of the cadBA operon encoding the lysine decarboxylase CadA and the lysine/cadaverine antiporter CadB. Under non-inducing conditions, the lysine-specific transporter LysP inhibits CadC. When cells are exposed to low pH in the presence of lysine, the interaction between LysP and CadC is weakened, rendering CadC susceptible to protonation and transcriptional activation. The end-product of decarboxylation, cadaverine, binds to CadC and thereby inactivates this receptor.

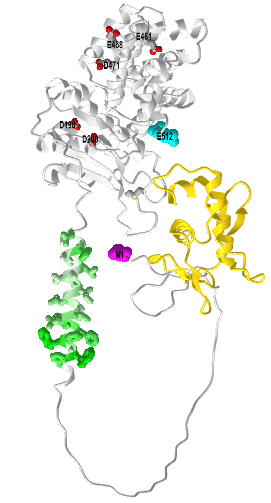

CadC is activated by two stimuli, low pH (less than 6.8) and the presence of external lysine (greater than 0.5 mM), which are perceived by different mechanisms. The periplasmic domain of CadC directly senses a decrease in pH. It has two distinct subdomains: the N-terminal subdomain comprises a mixture of β-sheets and α-helices, and the C-terminal subdomain consists of a bundle of 11 α-helices. A patch of acidic amino acids (D198, D200, E461, E468, D471) detect changes in the external pH through protonation changes, altering their charges and noncovalent interactions between the subdomains/monomers. This in turn leads to dimer formation of the periplasmic domain, triggering receptor activation.

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of a Transcriptional activator CadC One Component Model - AlphaFold Model (P23890)

The gold represents the N-terminal CadC DNA binding domain. The green (hydrophobic) is the transmembrane helix and the gray is the outside periplasmic domain containing the acidic side chains (D198, D200, E461, E468, D471). The N term Met is magenta spacefill and the C-terminal Ser is cyan spacefill. Again, the long intrinsically disordered region between the DNA binding domain and the transmembrane domain would have a more defined structure in the actual membrane-bound form and probably form additional interactions with other molecules. It also presumably leads to a conformation change in the DNA binding domain which leads to its interaction with the target DNA.

CadC senses external lysine only in interaction with the lysine-specific permease LysP. In addition, the products of lysine decarboxylation, CO2, and cadaverine, act as feedback inhibitors on CadC. Cadaverine binds to the periplasmic domain of CadC, thereby switching off cadBA transcription.

Two Component System

Two-component Histine kinase systems have (in general) two main components

- A HK sensor protein binds a ligand in a receptor binding domain leading to the transfer of a gamma-phosphate from ATP to a His by the kinase domain. This component is often called a transmitter. The conserved His located in the H box.

- a separate response regulator (or effector) protein containing a reactive Asp which receives the phosphate from p-Histidine. The conserved Asp (D) is located in the D box. This activates the response regulator protein. This component is often called the receiver. It may also transfer it to another His in a phospho-relay system.

Histidine kinase/response regulator systems are the most commons in bacterial signaling across the membrane. In contrast to the myriad of serine/threonine (S/T) and less abundant tyrosine (Y) kinases that dominate signaling in mammals, the histidine kinase predominates in bacterial signaling.

Before we present more detail on the two-component system, let's looks at protein kinases in general and see what is different about histidine kinases. ATP is a donor of a gamma-phosphate in both S/T/Y and H kinases. However, their products are very different energetically. pS, pT, and pY of the O-phosphoproteome are all phosphoesters, which are not high energy compared to their hydrolysis products. (Remember, there is no such thing as a "high energy" bond.) In contrast, pHis, a member of the N-phosphoproteome (along with pLys and pArg), is not a phosphoester but more analogous to the mixed anhydride of a carboxylic acid as in the case of phosphorylated aspartic acid. In pHis and pAsp, there is an electronegative N (in pHis) and O (in pAsp) bridging two atoms which are each connected to another atom by double bonds. This type of structure, which allows for bridging resonance between the center N (in pHis) and O (in pAsp) is also high energy compared to its hydrolysis products. Hence the phosphorylation of His by ATP is not as energetically favored as the phosphorylation of Ser, Thr, or Tyr since it produces another high-energy molecule (with respect to its hydrolysis products.

Since the pHis is also considered high energy compared to its hydrolysis products, it can act as a phosphate donor to another receiving group. That could be water in a simple hydrolysis reaction or, if sheltered from water in an active site of an enzyme or receptor, to a carboxylate receiver like Asp to form another high energy mixed anhydride which is isoenergetic with the pHis. This is the process that occurs in the two-component His kinase signaling pathways in bacteria. Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) compares Ser, Thr, Tyr, and His kinase reaction and their products.

The more common mammalian S/T/Y kinases are shown at the top and the histidine kinase at the bottom. Note that phosphorylation of His can occur at either nitrogen to produce either τ- or π-pHis. In the two-component system, instead of water being the receiver of the phosphate from the pHis (hydrolysis), the receiver is an Asp or another His in the same His Kinase receptor or in another receiver protein (shown in gray and its phosphorylated blue form in Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\). You can imagine the phosphate on the original pHis jumping to a receiver, which then donates it to another receiver in the signaling process in a relay process.

Proteins like the receptor His-kinase proteins in two-component systems have multiple domains with different functions. It's really helpful to present domain structure diagrams to help in understanding the protein's structure and activities. At the same time, the domain structures determine by various bioinformatic programs vary. Nevertheless is it useful to see multiple representations of domain structure, especially if they are shown in conjunction with actual structures.

The first component of the two-component signaling system is the receptor His-kinase which can be viewed as a stimulus-activated kinase (much like receptor tyrosine kinases - RTKs). The second component is the response regulator protein, which is typically a second protein. Each of these in turn has its own domain structure. For example, the periplasmic sensing domain regulates the kinase domain of the receptor His-kinase (component one). The phosphate from the p-His in the first component is transferred to an Asp in the second component. The domain structures and phospho-transfer are illustrated in Figure \(\PageIndex{5\) below.

Panel (A) shows a prototypical two-component pathway. The transmembrane sensor HK (component one) and a cytoplasmic response regulator (RR) protein (component two) are shown. (Note: the actual protein is a dimer in the membrane.) The transmembrane segments are labeled TM1 and TM2. N, G1, F, and G2 are conserved sequence motifs in the ATP-binding domain. HK catalyzes ATP-dependent autophosphorylation of a specific conserved His residue within the HK dimerization domain. The phosphoryl group (P) is then transferred to a specific aspartate residue (D) at the conserved RR domain (component two). Phosphorylation of this domain usually triggers an associated (or downstream) effector domain, which ultimately produces a specific cellular response.

Panel(B) shows a multi-component phospho-relay system that often involves a variant of HK with an additional internal C-terminal RR domain. In these complex systems, at least two His–Asp phosphoryl transfer events occur, typically involving a His-containing phosphotransfer protein (HPT) operating as a His-phosphorylated intermediate.

In most prokaryotic systems, the response is directly carried by the RRD which functions as a transcription factor. Two-component systems also exist in some eukaryotes. They often interact with other downstream signaling pathways such as the MAPK system. However, in eukaryotic systems, the TCS are placed at the start of the pathways and establish an interface with more conventional signaling strategies such as mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase and cyclic nucleotide cascades

The domain structure shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\) doesn't show the actual orientation of the proteins in a membrane sytem. Orientation is important since the sensing domain of the HK receptor must be in the environment of the stimuli. Stimuli can be encountered in the periplasmic (equivalent to extracellular) region, in the transmembrane region and in the cytoplasm. Variants of the HisK receptors exist that recognize stimuli in each of these locations as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\).

Most histidine kinases sense extracellular signals (left-hand structure). All have their cytoplasmic transmitter domains which contain the pHis. As mentioned previously, the histidine kinases are dimeric, so when activate they phosphorylate a His on the other monomer (transphosphorylation). In addition to the H box with the reactive histidine, they also have N, G1, F, and G2 boxes. The H box is also involved in dimerization The transmitter domain can be further divided into two parts: the H-box is involved in dimerization and obviously in phosphotransfer. The figure also shows the CA domain (HK-type ATPase catalytic or HATPase_c), also known as the catalytic and ATP-binding (CA) domain (Figure 1.3-3)

The histidine kinase senses a variety of stimuli in its sensory domain. The stimuli can be generally grouped into organic (e.g. dicarboxylates, citrate, etc), ions (e.g. Mg2+, H+, K+), gaseous ligands (e.g. O2, N2), and physical changes (osmolarity/turgor, light, and temperature). Stimuli are "sensed" by a variety of different characterized folds. Some common sensing domains are PAS (Per-ARNT-Sim), CHASE (cyclase/histidine kinase-associated sensing extracellular), four-helix bundle (4HB), and NIT (nitrate and nitrite-sensing) classes. We will focus on one particular His kinase system, histidine kinase KdpD.

Histidine kinase KdpD and the regulation of K+ ion concentration

It is often difficult to identify the primary stimulus for a receptor, as exemplified by the histidine kinase KdpD which, together with the response regulator KdpE, controls the expression of a high-affinity K+-uptake system in many bacteria. K+ is the most abundant cation in all living cells, especially in bacteria it is crucial for the regulation of cell turgor and intracellular pH and the activation of several enzymes. To ensure a sufficient supply of K+, most bacteria have more than one K+-uptake system. For example, E. coli has at least three such systems, the constitutively expressed systems Trk and Kup, and the inducible high-affinity K+-uptake system KdpFABC. The genes kdpF, kdpA, kdpB, and kdpC form an operon that codes for four inner membrane proteins. The kdp operon is induced when E. coli is grown under K+ limitation, lacks the major K+ transporter Trk or has an increased need for K+ when under hyperosmotic stress. Under all these conditions, the membrane-integrated histidine kinase KdpD autophosphorylates and transfers the phosphoryl group to the cytoplasmic transcriptional (response) regulator KdpE, resulting in the induction of the kdp operon, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\).

What is amazing is that KdpD has not only kinase activity but also phosphatase activity towards phosphorylated KdpE, which switches the signaling cascade off. It is a bifunctional enzyme/receptor. A single substitution (T677A) in the C-terminal domain results in no phosphatase activity.

Hence KdpD can be thought of as a bifunctional receptor acting as both kinase and phosphatase to regulate gene expression. The bifunctional receptor histidine kinase KdpD acts as both an autokinase (including phosphotransferase) and phosphatase for the response regulator KdpE. Phosphorylated KdpE activates the expression of the genes encoding the high-affinity K+ transporter KdpFABC. KdpD autokinase activity depends on the external K+ concentration, and the phosphatase activity is influenced by the internal K+ concentration. K+ ions don't move through a channel in KdpD but through the KdpFABC.

The cartoon in Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\), as with all cartoons, can be misleading with respect to scale. Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of the actual membrane domain of E. coli histidine kinase receptor KdpD (2KSF)

.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=334&height=308)

4 helices space the membrane. Hence both the N-terminal and C-terminal domains are actually in the cytoplasm, not one in the periplasmic space and one in the cytoplasm as you would infer from Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\). The actual periplasmic (outsithe de of cell" domain) consists of only about 6 amino acids. Hence it most clearly is represented by the middle model in Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\). Mutations of key residues in the periplasmic loop region (P466A, T469A,, L470A and V472A) drastically affect K+ recognition. Actually how it "senses" periplasmic K+ ions is not clear.

Domain representation

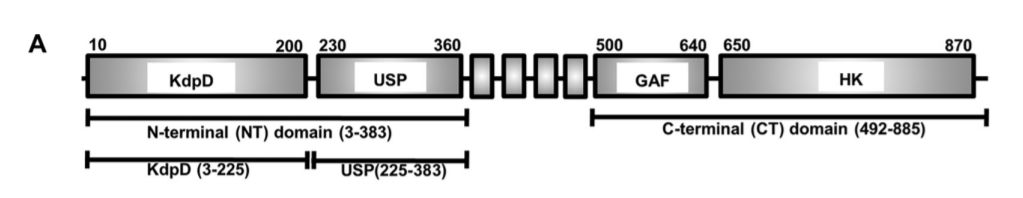

We present three different domain diagrams for KdpD in Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\), not to confuse readers, but to show the utility of mulrepresentationstation they are likely to encounter in reading the literature.

|

Moscoso et al. Journal of Bacteriology. 198 (2016) http://dx.doi.org/10.1128 /JB.00480-15. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license |

|

B. Pfam |

|

C. Dutta et al. JBC. 296, 100771 (2021). DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbc.2021.100771. Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) |

Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\): Multiple representations of the domain structure of the histidine kinase KdpD

In panel A, the 4 boxes btw 360 and 500 are 4 transmembrane helices, which would not be evident in a simple cartoon as in Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\). In panel B, the domains are shown as follows:

- Green: K+ channel His kinase sensor domain 21-230;

- Red: 4 transmembrane helices 402-508; the helices are lumped together in the red domain representation;

- Blue: GAF domain 527-644;

- Yellow and Purple combo: HK domain;

- Yellow: HisKinase A phosphoacceptor domain 663-730 which contains the His acceptor, in effect the substrate of the kinase domain;

- Purple: His Kinase/HSP 90 is like ATPase 773-883.

The domain structure in panel C is the most detailed and also has the domain structure of the receiver (response regulator). Again the periplasmic domain which senses K+ consists of only a few amino acids, 424-427 and 467-474. Neither representations A nor B show that the major N-terminal and C-terminal halves of the protein are in the cytoplasm. Panel C shows more information about the domains, their function, and their orientation in the intracellular environment. It turns out there is also a sensor for intracellular K+ions, which is depicted in Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\).

A central question is how histidine kinase KdpD responds to changes in K+ concentrations. Both the kinase and phosphatase activities are regulated by K+.

- When periplasmic (extracellular) K+ is > 5 mM (high), the ion appears to bind to the small extracellular loops (see Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\)), which inhibits the autokinase activity. Under the same conditions the intracellular C-terminal tail senses K+ and activates the phosphatase activity, which cleaves its pHis. These combined effects inhibit high-affinity K+ transport.

- When periplasmic K+ becomes low, kinase activity is activated and the protein is autophosphorylated, ultimately leading to the activation of the gene for the high-affinity K+ transporter KdpFABC. As long as intracellular K+ levels are high, the phosphatase is active. When intracellular K+ levels drop sufficiently, the phosphatase becomes inhibited, which further simulations the transcription of both high-affinity K+ transporter KdpFABC.

Hence the histidine kinase KdpD system is regulated by both periplasmic and cytoplasmic K+ ions.

Yet another signal regulates the KdpD His Kinase receptor two-component signal. What has been conspicuously absent from this discussion about signaling in bacteria is the involvement of second messengers like cAMP (which activates Protein Kinase A and some membrane proteins). There does appear to be one major second messenger in bacteria - cytoplasmic di-AMP (c-di-AMP), whose structure is shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\).

It binds in the N-terminal region of KdpD His Kinase receptor protein "sensor" domain region to a specific domain called the Universal stress protein (USP) domain as shown in panels A and C of Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\). Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of the Staphylococcus aureus universal stress protein (USP) domain of KdpD histidine kinase in complex with second messenger cyclic diadenosine phosphate (c-di-AMP) (7JI4)

domainKdpD_Hkinase_c-di-AMP_(7JI4).png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=348&height=280)

"Dual sensing thus emerges as a highly optimized regulation strategy. The key advantage of this strategy is that it confers on cells the ability to directly sense changes in both the supply of and demand for the limiting resource. It is, in fact, analogous to strategies that are widely used in control engineering, e.g. modern heating systems work with both exterior and interior thermometers to ensure constant room temperature."

Escherichia coli nitrate/nitrite sensor kinase NarQ

Let's examine another TCS protein, the Escherichia coli nitrate/nitrite sensor kinase NarQ, to see how the binding of a ligand to the periplasmic domain might transmit a signal so far into the cell through the plasma membrane. We won't discuss the His Kinases that lack transmembrane regions (about 1/4). The sensor domain hence is mostly in the periplasm, followed by the transmembrane domain (see Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\)), followed often by a cytoplasmic HAMP domain, with a four-helical parallel coiled-coil. The HAMP domain transmits the signal to downstream signaling domains like Dhp in the protein.

Nitrate/nitrite is sensed by two different two-component systems, sensing systems NarX-NarL and NarQ-NarP, which regulate anaerobic respiration. NarQ phosphorylates two different proteins, NarL and NarP in the presence of nitrate or nitrite and dephosphorylates both proteins in the absence of ligands. Both NarQ (and NarX) have seven domains: a four-helical periplasmic sensor domain, TM bundle, HAMP domain, so-called signaling helix, (S-helix), GAF-like domain, dimerization and histidine phosphotransfer domain, and, finally, catalytic kinase domain, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{12}\).

Pane (a) shows the architecture of NarQ. Note that the functional protein is homodimeric. Approximate domain boundaries, according to InterPro [17], are TM1, residues 14–34; sensor, 39–146; TM2, 147–167; HAMP, 172–227; S-helix, 228–246; GAF-like, 247–360; DHp, 361–425; CA, 424–560.

Panel (b) shows the overall structure of the sensor-TM-HAMP fragment of the R50S mutant (which allowed crystallization). The position of Ser50 is highlighted with spheres. The backbone structure is identical to that of the WT protein.

Panel (c) shows the structure of the ligand (nitrate) -binding site in the WT protein.

Panel (d) shows the structure of the ligand-binding pocket in the R50S mutant. Asp133 is reoriented towards Ser50. 2Fo−Fc electron density maps are contoured at the level of 1.2 × r.m.s. Putative water molecules are shown as red spheres. Gushchin et al. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3110; doi:10.3390/ijms21093110. Creative Commons Attribution. (CC BY) license. (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Although the sequence identity between NarQ and NarX is ~28%, their ligand binding sites—membrane-proximal parts of the sensor domain’s helices H1 called P boxes—are very well conserved: 14 out of 15 amino acids (residues 42–56 in NarQ) are identical, and the differing ones, Ile 45 in NarQ and Lys49 in NarX, are responsible for the differentiation between nitrate and nitrite.

It appears that the ligand-induced conformational change in the ligand-binding site is helical rotation, which results in diagonal scissoring of the sensor domain helices, leading to the change in the secondary structure of the sensor-TM linker and, eventually, piston-like shifts of the transmembrane α-helices.

Nitrate causes changes in the transmembrane region when the apo (nitrate free) and holo (nitrate bound) state structures of NarQ are compared. On binding of nitrate, the induced conformation changes in NarQ have been described as a "combination of changes in the lateral arrangement of the TM helices and piston-like shifts of the helices in the direction perpendicular to the membrane plane." This results in either symmetric or asymmetric changes and scissoring of the transmembrane helices (based on two different crystal structures of the holo-form. A "piston-like" movement of the helices is observed on both holo-forms.

Results show that the binding of ligand to NarQ causes a piston-like displacement of the TM helices, which is accompanied by extensive symmetric or asymmetric rearrangements and scissoring of the TM helices. The rearrangements are different in the two presented holo-state structures, but the piston-like displacement is perfectly conserved. Thus, the latter appears to be a more robust mechanism of TM signal transduction.

Figure \(\PageIndex{13}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of a fragment of nitrate/nitrite sensor histidine kinase NarQ (mutant R50K) in the symmetric holo state (5IJI)

.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=176&height=316)

A homodimer (cyan and magenta) is shown with the N-terminus and C-terminus on the cytoplasmic side. Each monomer passes through the membrane with an alpha-helical domain twice. Nitrate is shown in spacefill in the extracellular domain outside of the outer leaflet (red spheres) of the membrane.

Figure \(\PageIndex{14}\) shows the conformational transition going from the symmetric apo state (5JEQ) magenta to the symmetric holo state (IJI) (cyan) with bound nitrate (not shown).

Conformational changes in the HAMP domain seem to amplify and convert the piston-like conformational changes in the transmembrane domain. Note the splaying out to the helices at the bottom (cytoplasmic end) in the apo form.

Phototaxic Photoreceptors

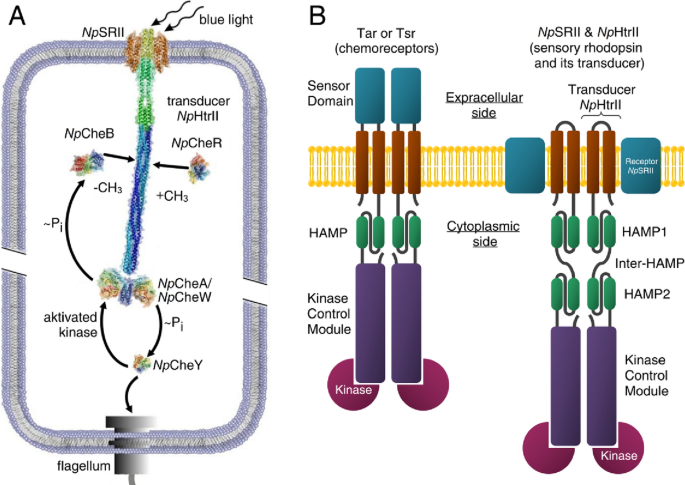

We have discussed two-component systems that have a His-Kinase receptor transmitter protein. There are two other major types of bacterial receptors, chemoreceptors (involved in chemotaxis) and photoreceptors, involved in phototaxis. These often have similar modular domain structures. Chemotaxis receptors are, like the His Kinase receptor, dimers with extracellular domains that bind the chemotactic signal. The photoreceptors appear to be active as a trimer of dimers.

The basic dimeric structure contains the microbial light sensor rhodopsin which contains the chromophore opsin, and its transducer Htr. In the halobacteria N. pharaonis, (archaeal, not a bacterial cell) the proteins are sensory rhodopsin II (NpSRII) with its transducer (NpHtrII), mediates negative phototaxis in halobacteria N. pharaonis.

Microbial rhodopsins are phototransducing proteins with a conjugated chromophore retinal, covalently attached to the protein opsin through a Schiff base (imine) linkage. The holoprotein (opsin with the attached retinal) is called rhodopsin. Retinal is derived from beta-carotene. The structures of animal and microbial retinals are shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{15}\).

When light of the correct wavelength is absorbed, an electron in a pi molecular orbital in retinal is promoted to a pi antibonding molecular orbital, breaking a 2 electron pi bond in the structure at a certain site in the isoprenoid chain, allowing rotation around the now single bond. The final result after the electrons return to the ground state is photoisomerization of the trans 13-14 and cis 11-12 bonds in microbial and animal retinal, respectively, to their respective cis 13-14 and trans 11-12 configuration. This conformational change in the bound retinal induces a conformational change in the protein opsin, leading to signaling.

Figure \(\PageIndex{16}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of one monomeric of bacteria rhodopsin (1C3W) containing retinal attached through a Schiff base to Lys 216.

.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=274&height=314)

The covalently attached retinal is shown in gray spacefill. The protein opsin is a membrane protein that spans it with seven helices. Hence it is very similar to a GPCR.

In the phototaxic receptor, when light is absorbed by rhodopsin (NpSRII), the resulting conformational change in the protein causes conformational changes in the transducer protein NpHtrII associated with it, leading to signaling through a two-component signal system. (The chemotaxis response to chemical signals occurs through a similar but ligand-induced process.) Figure \(\PageIndex{17}\) shows the structure of the Archaeal photoreceptor complex.

A-G, TM1, and TM2 are the transmembrane helices. The cytoplasmic part of NpHtrII consists of two HAMP domains (HAMP1 and HAMP2) connected by an α-helical linker (Inter-HAMP) and the kinase control module. Primes denote symmetry mates of the complex. Ishchenko, A., Round, E., Borshchevskiy, V. et al. New Insights on Signal Propagation by Sensory Rhodopsin II/Transducer Complex. Sci Rep 7, 41811 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep41811. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Figure \(\PageIndex{17}\) shows a more details representation of both the transmitter and receiver in the Archeal two-component phototransduction system and how it leads to phototaxis.

Figure \(\PageIndex{17}\): Signal transduction pathway in case of the two-component phototaxis system of Natronomonas pharaonis5 and domain architecture of membrane chemo- and photoreceptors of TCS. Ryzhykau, Y.L., Orekhov, P.S., Rulev, M.I. et al. Molecular model of a sensor of the two-component signaling system. Sci Rep 11, 10774 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-89613-6. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Pane (A) shows Light activated sensory rhodopsin II (NpSRII) induces conformational and/or dynamical changes in the transducer (NpHtrII), which are converted by two HAMP domains and conveyed along the 200 Å long transducer to the tip region. Activated by the transducer histidine kinase CheA (bound to the adapter protein CheW) undergoes auto-phosphorylation and further transfers the phosphate group to the response regulators CheY or CheB. CheY affects the rotational bias of the flagellar motor, while the methylesterase CheB along with the methyltransferase CheR controls the adaptation mechanism.

Panel (B) shows cartoon representations of the chemoreceptor dimer (Tar and Tsr in complex with kinases) from E. coli and of the photosensor dimer of the complex of the sensory rhodopsin II with its cognate transducer NpHtrII and kinases from N. pharaonis.