28.7: Calcium Signaling

- Page ID

- 79161

The following is adapted directly and modified from Sharma et al. Biomedicines 2021, 9(9), 1077; https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines9091077. Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Introduction

Ca2+ is central to numerous cellular processes and functions. Its chemical features, including a low hydration energy, high polarizability, relative flexibility of coordination sites and bond length, and large concentration gradient across cellular membranes (100 nM intracellular to 2 mM extracellular) due to low intracellular levels make it the ion of choice at the core of cellular signaling in prokaryotes and eukaryotes alike.

In studying calcium ion signaling we will focus on four key areas:

- Buffering of intracellular Ca2+ ion concentrations: Basal low levels must be maintained, which allows transient increases to act as signals. Ca2+ ions hence are no different from other second messengers like cAMP, for example. What matters is the rise from a basal level to a threshold concentration level that allows binding to signaling proteins and subsequent signal transmission.

- Storage of intracellular Ca2+: Calcium ions are stored in organelles such as ER, mitochondria, and lysosome. The ions must be released in the presence of specific signals, then returned to the storage organelle to maintain basal Ca2+ levels.

- Signaling pathways activated by Ca2+ ion: We have seen many pathways simulated by a rise in second messengers and by phosphorylation of lipid and protein molecules in interconnected pathways. We will return to several pathways we have previously studied to see how they integrate with Ca2+ in signaling processes.

- Ca2+ binding proteins and their binding partners in signaling pathways: We will focus on one key Ca2+ binding protein, calmodulin (CAM), and the kinase that it activates, Ca2+/CAM protein kinases or CAMKs.

The next two sections are adapted and modified from Sharma et al. Biomedicines 2021, 9(9), 1077; https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines9091077. Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Buffering of intracellular Ca2+ on concentrations

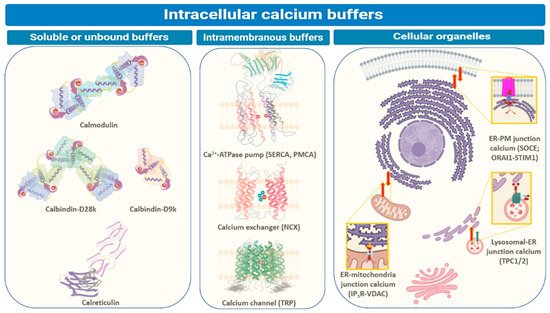

Calcium ions, like the hydronium ion, must be buffered in cells otherwise its potential as a signaling agent would be compromised. The mechanisms adopted by cells for intracellular Ca2+ buffering involve sequestration by special proteins as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\).

Intracellular Ca2+ levels are managed through binding to special proteins or sequestration within different cellular compartments. The three main ways by which intracellular Ca2+ is buffered are depicted in Figure 1. These include soluble or unbound proteins that are found in the cytosol or inside organelles, membrane proteins (generally Ca2+ channels, ATP-driven pumps (SERCA or PMCA), and ion exchangers (NCX), inside organelles like endoplasmic reticulum (ER), mitochondria, acidic vesicles (mainly lysosomes and Golgi bodies) or organelle junctions (endoplasmic reticulum-plasma membrane (ER-PM), endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria, or endoplasmic reticulum-lysosomes). The major players regulating inter-organellar Ca2+ transfer are IP3R (inositol-3,4,5-triphosphate receptor), NCX (sodium-Ca2+ exchanger), ORAI1/CRACM1 (Ca2+ release activated modulator 1), PMCA, (plasma-membrane Ca2+ ATPase), SERCA (sarco-endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase), STIM1 (stromal interaction molecule 1), SOCE (store-operated Ca2+ entry), TPC1/2 (two-pore channel), TRP (transient receptor potential) and VDAC (voltage-dependent anion channel). We will discuss some below.

These proteins are involved in sequestering cytosolic Ca2+ upon sensing an increase in its levels and participate in relaying the associated cellular messages. Other proteins that work as intracellular Ca2+ buffers exist in the lipid bilayers, plasma membranes, or organelle membranes, like pumps or transporters. Apart from these proteins, intracellular Ca2+ is regulated by inter-organellar transport and the influx of Ca2+ ions from extracellular space.

Storage of intracellular Ca2+ - Proteins

Soluble and Unbound Intracellular Proteins: Calmodulin, Calbindin, and Calretinin

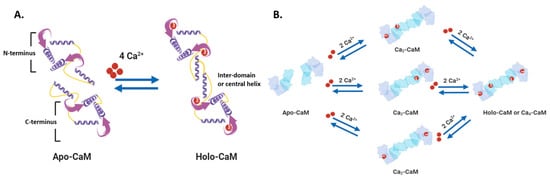

Nonmembrane-associated proteins inside a cell can act as both Ca2+ sensors and buffers. Most of these proteins have EF-hand motif(s) that allows Ca2+ ions to bind and trigger changes in protein folding, influencing downstream or linked cellular pathways. Calmodulin (CaM) is one of the best-studied and ubiquitously expressed Ca2+-sensing proteins known to play a key role in intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis. It is a prototype for intracellular Ca2+ sensors. It has a 148 amino acid structure with two Ca2+-binding sites in two separate lobes, each with two EF-hand motifs. The lobes are connected in the holo (Ca2+-bound form that binds other proteins. N- and C-termini alpha-helices with a Ca2+ coordination loop in between providing affinity for Ca2+ ion docking and sequestration. The ability of CaM to transmit a change in free intracellular Ca2+ levels into a signal depends on the conformational flexibility of the Ca2+-dependent (apo) form. CaM can exist in a Ca2+-free closed conformational state (Apo-CaM), a semi-open (Ca2-CaM), or an open state (Holo-CaM or Ca4-CaM) after Ca2+-binding as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\).

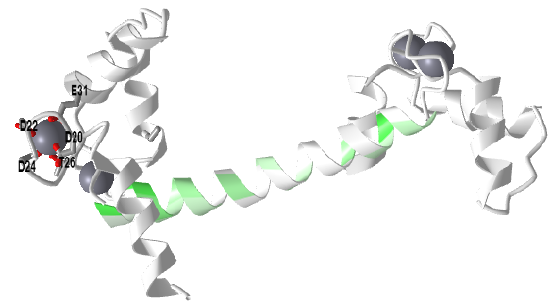

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of Holo-calmodulin with 4 bound Ca2+ ions (1CLL)

Side chains interacting with one Ca2+ ion in an EF-hand is shown in the model. The central helix is colored based on hydrophobicity with green indicating more hydrophobic. This amphiphilic helix can bind target proteins in this region through nonpolar interactions.

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) shows the change in conformation going from the apo form (without Ca2+) to the holo-form with the fully-formed central helix connecting to the two lobes of the "dumbbell".

Differential Ca2+ binding to the two lobes of CaM makes fast buffering of a wide range of free intracellular Ca2+ possible for this protein. The presence of methionine residues in its lobes and the plasticity of the central linker in its structure also provides CaM with properties to function as an adaptor protein in intracellular Ca2+ signaling. CaM can bind to several targets or effector molecules over a variable distance and in multiple orientations to mediate change in intracellular Ca2+ signaling. Some major effector proteins that are regulated by CaM binding and are relevant for Ca2+ homeostasis include EGFR, PI3K, and connexins.

CaM is required for spatial and temporal regulation of [Ca2+]as evident by its role in modulation (activation or inactivation) of Ca2+ pumps (such as PMCA and SERCA) and Ca2+ channels (such as CaV1.3, TRPV5 and 6, ORAI). CaM also acts via serine/threonine kinases known as Calmodulin-activated Kinases (CaMKs) to influence cellular processes like proliferation (for example, centrosome duplication at G1/S or anaphase to metaphase transition via CaMKII). We will discuss those in detail below.

Integral Membrane protein molecular buffers: SERCA, PMCA, NCX, and TRP

Integral membrane protein Ca2+ buffers primarily translocate free Ca2+ between domains and organelles. These mainly comprise ion exchangers, channels, and ATP-driven pumps. SERCA, Sarcoendoplasmic Reticulum Ca2+ ATPase, is an ATP-dependent ion pump known to significantly maintain free cytosolic Ca2+ concentration via actively pumping the ion into the endoplasmic reticulum (or sarcoplasmic reticulum in muscle cell). They share a general structure that includes 10-pass transmembrane helices and three cytoplasmic domain lobes as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)

P-type Ca2+-ATPases also exist within the plasma membrane and maintain cytosolic Ca2+ levels by transferring them into the extracellular space. The Plasma Membrane Ca2+ ATPases (PMCAs) can PMCAs transport one Ca2+ ion per ATP molecule which differs from the two Ca2+ ions per ATP molecule stoichiometry of SERCA. The general structure of such Ca2+ transporters comprises 10 transmembrane segments with large cytosolic loops TM 1–2 and TM 3–4, a cytosolic N- and C-termini tails are shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\), panel A below.

The cytoplasmic region of PMCA (left) has three loop structures with binding sites for signaling molecules like CAM. They also have phosphorylation sites for additional regulation. The C-terminal tail contains additional CAM sites as well as a PKA site. It has a PDZ domain that can anchor the protein to cytoskeletal components. Differential RNA processing lead to variations in the amino acid sequence in this region and hence binding specificity. The binding of CaM reverses auto-inhibition of the pump due to conformational shifts which displace C-tail from cytosolic loops. Other means of autoinhibition reversal include phosphorylation of C-tail (Ser/Thr residues) by protein kinase A or C, proteolytic cleavage of C-tail, or dimerization via the C-terminus.

Transient Receptor Potential (TRP) channels have a similar function in neurons, epithelial and immune cells. The Mammalian TRP channel superfamily is composed of 28 family members belonging to six subfamilies—TRPC (Canonical), TRPA (Ankyrin), TRPM (Melastatin), TRPV (Vanilloid), TRPP (Polycystin), and TRPML (Mucopilin)—that differ in their sensitivity to various sensory stimulations and affinity for cations (including Ca2+ ions) sequestration. Commonly, TRP family members share a structure with six transmembrane domains, intracellular N- and C-termini, and a pore-forming TM 5–6 loop. The cytoplasmic C-terminus of each subunit is a site for protein interaction and post-translational modification. The C-tail of these channels can have PDZ protein binding domains (TRPV and C), sites for interaction with G-proteins (Gq/11)/calmodulin/PLCβ, ADP-ribose binding (NUDIX; TRPM2), or PLC-interacting kinase (PLIK; TRPM6 and 7) domain.

TRP channels act as activators, integrators, as well as downstream effectors of Ca2+ signaling at the plasma membrane and in intracellular compartments. Many members of the TRPC subfamily are activated by DAG (diacylglycerol) which is produced by PLC β- or γ-mediated cleavage of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) after the ligand binding at GPCRs or RTKs. TRPP1/2, TRPA1, TRPM8, and TRPV1-4 are all expressed on the ER membrane. At this site, PLC-independent activation of the TRP channels (such as TRPV1) is suggested to induce ER Ca2+ release via inositol triphosphate receptor (IP3R) which further triggers bulk entry of extracellular Ca2+ into the cell. On the flip side, cytosolic Ca2+ regulates the activity of TRP channels in response to physiological stimuli. This regulatory effect is usually through CaM binding (inhibition of TRPV5, TRPV6, and sensitization of TRPV3) and indirectly through CaM-binding kinase II (CaMKII). These activities are shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\).

Storage of intracellular Ca2+ ions - organelles

Endoplasmic Reticulum: STIM, ORAI, IP3Rs, and TRPC1 in SOCE and SOCIC Ca2+ Entry Models

The ER serves as the largest and most dynamic organelle reservoir for intracellular Ca2+ and is therefore central to many signaling processes for protein synthesis, folding, and post-translational modifications. In contrast to the cytosol, ER Ca2+ ion levels can range from 100 uM to 1 mM based on the cell type. ER, and other intracellular organelles buffer excessive cytosolic Ca2+ by both housing Ca2+-binding proteins (example: calreticulin in ER) and via active transport (example: SERCA pumps in ER).

- Depletion of Ca2+ from the ER lumen actuates an indirect mode of Ca2+ entry into the organelle which is termed Store-Operated Ca2+ Entry (SOCE) or Ca2+ Release Activated Ca2+ (CRAC) entry; it is activated when plasma membrane receptors like PLC-coupled GPCRs (but not voltage-gated channels) trigger Ca2+ ion release from the organelle.

- Exhaustion of the intraluminal ER Ca2+ ion store following such prolonged release is then sensed by STIM (Stromal Interaction Molecule) tethered to the ER membrane and subsequently relayed to the CRAC channels on the plasma membrane.

Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\) shows the domain structures of STIM 1/2, ORAI 1-3, and IP3Rs (panel A) and the mechanism of Ca2+ influx into the cell (B).

IP3 Receptors (IP3Rs), on stimulation by IP3, open and allow Ca2+ influx from the organelle lumen into the cytoplasm. After activation of IP3Rs on the ER membrane by ligand IP3 and cytosolic Ca2+ from activation of phospholipase C, STIM dimers are activated once the luminal Ca2+ concentration drops below basal levels. These receptors provide intracellular Ca2+ ions for downstream Ca2+ signaling including NFAT-mediated transcription. The red semi-circle in the ER represents high luminal Ca2+ levels, the pink semi-circle is for moderately low Ca2+ ion concentration, and the pale semi-circle indicates extremely low Ca2+ concentration. CC, coiled-coil; NFAT, nuclear factor of activated T-cells; SAM, sterile alpha motif; SOAR, STIM1 Orai1-activating region; TM, transmembrane.

Mitochondria and Acidic Vesicles (Mainly Lysosomes)

Mitochondria also play a critical role in maintaining Ca2+ ion levels in the cytosol and endoplasmic reticulum. They are found mostly aggregated around the nucleus and store similar levels of intracellular Ca2+ as the cytosol (0.1 μM). Electrochemical proton gradient or membrane potential (Ψmt = −150 to −180 mV) and close association to the ER are the two key factors responsible for Ca2+ uptake in mitochondria. The free movement of small molecules (less than 5 kDa) from the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM) into the inner mitochondrial space and their impermeability across the latter generates a high electrochemical proton gradient for ATP synthesis. This gradient simultaneously draws Ca2+ ions from the cytosol.

Transfer of Ca2+ ions from ER to mitochondria occurs at specialized microdomains or contact sites known as Mitochondrial Associated Membranes (MAMs). These are characterized by the ER and OMM apposed at 10–25 nm from each other and are strewn with a cluster of channels, transporters, exchangers, and tethering proteins for facilitating Ca2+ ion transfer. IP3Rs localized at the ER side of the MAMs release Ca2+ ions that gate voltage-dependent anion channels (VDACs) located on the OMM. VDACs (1, 2, and 3) are 30 kDa polypeptides having a 19-strand beta-barrel structure that regulates the flux of metabolites (polyvalent anions like ADP and ATP) across the outer mitochondria membranes. These channels transport cations including Ca2+ more readily than anions like chloride. Due to voltage-dependent electrostatic gating, the ion selectivity and flux across VDACs change between open and closed states. Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\) shows couped mitochondrial and lysosomal effects on intracellular Ca2+ signaling.

Primary components of Ca2+ signaling at the mitochondrial associated membranes (MAMs) include IP3R3 on the endoplasmic reticulum, VDAC1 on the outer mitochondrial membrane, and MCU complex on the inner mitochondrial membrane [151,154,156,161]. Transport of Ca2+ ions from ER to mitochondria plays a crucial role in cellular metabolism (autophagy), cell survival (during unfolded protein response and impinging cell death signals), lipid production, and distribution. F

While IP3 acts as the dominant Ca2+-mobilizing messenger, cADPR (cyclic ADP-ribose) and NAADP (nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate) are also known to modulate intracellular Ca2+ stores. cADPR evokes Ca2+ ion release from ER by acting on ryanodine receptors (RyR; counterpart of IP3R in myocytes and co-expressed in some other cell types). NAADP releases Ca2+ from acidic and/or secretory vesicles such as lysosomes and endosomes. In most mammalian cells, lysosomes comprise ~5 percent of the cell volume and store similar levels of intracellular Ca2+ (0.5 mM) as the ER. Due to their relatively smaller size than ER, lysosomes release nearly undetectable amounts of intracellular Ca2+ in response to NAADP trigger

Signaling pathways activated by Ca2+ ion

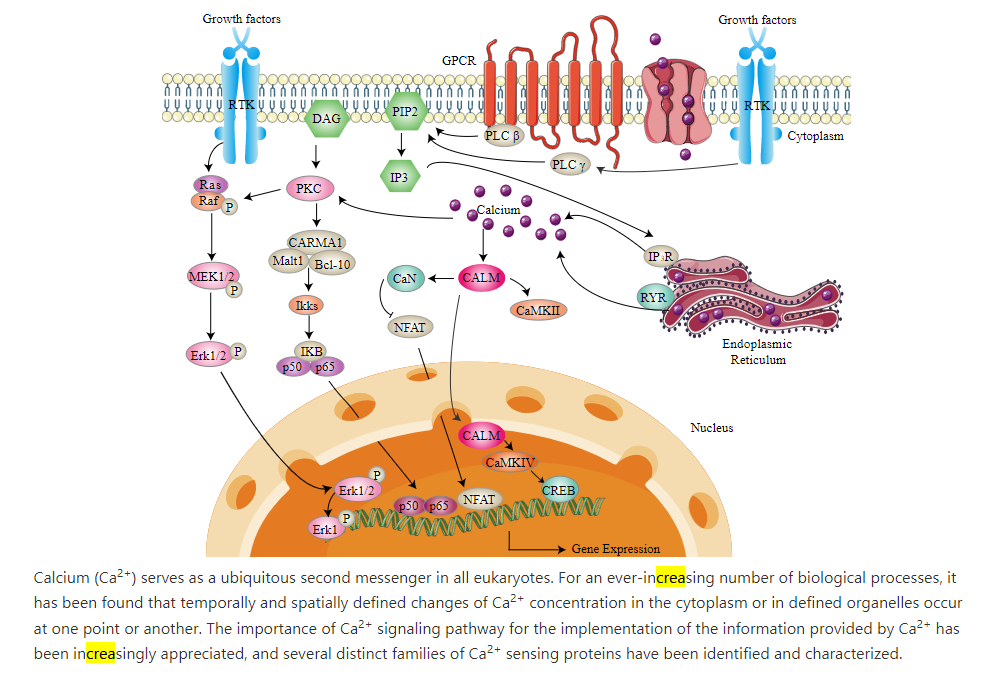

It is daunting to both readers and writers to introduce a myriad of new signaling pathways. Instead will show how Ca2+ signaling fits into other pathways we have already discussed. A summary showing how Ca2+ signaling integrates with other pathways is shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\).

An Overview of Calcium Signaling Pathway

Ca2+ signaling, as described above, requires ion buffer, organelle storage, and Ca2+ protein pumps and channels. The concentration (amplitude) and frequency of Ca2+ release affect signaling. Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\) shows the importance of upstream signaling through GPCRs, phospholipase C, RTKs, and IP3/DAGs. Ca2+ also enters the nucleus vs IP3 receptors (IP3Rs) and ryanodine recetors (RYR). An important family of cytoplasmic transcription factors, the Nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT), which are important in immune responses and development of muscle and nervous systems, are activated in calcium ion signaling.

As we described above, Ca2+ release from the ER is sensed by integral ER membrane proteins called STIMs. These bind Ca2+ ions as a buffering system, but if most of the ER calcium is depleted, the STIM-bound Ca2+ ions are also released. This lead to their self-association and ultimate activation or ORAI1, part of the CRAC complex in the cell membranes which allow extracellular Ca2+ ions to flow into the cell in a process called store-operated calcium entry (SOCE). Sufficient calcium now accumulates in the cell to activate the transcription factor NFAT through dephosphoylation by calcineurin (PP2B), also abbreviated CaN in Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\). NFAt then translocates into the nucleus and activates gene transcription. Also, it has been shown that nuclear calcium ions directly can activate the cAMP response element binding protein (CREB), a transcription factor that activates gene transcription. In addition the CAM:CAMKII complex can translocate into the nucleus. Calcium signals also activate ERK1/2-MAPK cascade.

Ca2+ binding proteins and their binding partners in signaling pathways

We have already described the key calcium-binding protein, calmodulin. On binding Ca2+, it undergoes a profound conformational change that allows it to interact with a family of key signaling kinases called CAM and Ca2+/CAM-Dependent Protein Kinases (CAMKs).

Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase is a key signaling protein activated by Ca2+ through the binding of calmodulin to CAMK. Activated CAMK is a Ser/Thr kinase. There are many types of CAMKs. We will focus on multifunctional CAMKs that can phosphorylate multiple target proteins. These are important in learning and memory, metabolism, and gene transcription. As with other kinases, they have catalytic and regulatory domains. Some like CAMK II have association domains that allow the formation of CAMKII multimers. In addition, they must have a CAM binding domain. As with all kinases, the CAMKs must be able to switch from an inactive to an active form.

CAMKI has a catalytic, substrate-binding domain and an autoinhibitory domain that blocks the active site. CAMKI is activated by an upstream kinase CAMKK (a naming system similar to the MAPK cascade) on the binding of Ca2+ to CAM. It helps regulate transcription, the cell cycle, hormone production, cell differentiation, actin filament organization, and neurite outgrowth. It is found in the cytoplasm and nucleus.

We will focus our attention on CAMKII, which has four isoforms (α, β, γ, and δ). It is activated by the binding of Ca2+/CAM which promotes autophosphorylation. After that, it is active in the absence of CAM. It is important in learning and memory and synapse formation in neurons and the regulation of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ transport in skeletal muscles.

They have an N-terminal catalytic domain and a C-terminal association domain that facilitates multimer formation into large holoenzymes with 12 or 14 CAMK monomeric subunits (a homomer or heteromer). These two domains are separated by a linker/regulatory domain that has a CAM binding site, an autoinhibitory region, and key Ser and Thr side chains that are targets for phosphorylation. Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\) shows the domain structure of the CAMKII monomer (a), the overall structure of a homododecamer (b), and the mechanism for activation of kinase activity (c).

T253, T286, and T305/306 are targets of autophosphorylation. M281/282 are also sites for oxidative modification. The C-terminal association domain allows multimer formation. It has a variable region that differentiates CaMKII subtypes. Panel (b) shows the multimer that forms on interactions of multiple association domains on different CAMKIIs. Panel (c) shows binding of CAM promotes the phosphorylation of key residues including T286 (through autophosphorylation).

In the absence of Ca2+/CAM T286 amino acid forms interactions with the catalytic domain to maintain the inactive conformation. The regulatory domain effectively autoinhibits the kinase domain. On the formation of the Ca2+/CAM/CAMKII complex, a conformation change ensues that frees the catalytic domain from autoinhibition and exposes the active site. Each subunit in the dodecamer is activated separately. T286 is now free to be "autophosphorylated" by an adjacent active subunit. Once phosphorylated, pT286 prevents the rebinding of the autoinhibitory region to the catalytic domain, even when CAM dissociates. At this point, CAMKII is active in the absence of Ca2+/CAM.

Phosphorylation of T286 also regulates its binding to target proteins for their phosphorylation. In addition, CAMKII can autophosphorylate T254 and T306 with further effects on activity. T306 is only autophosphorylated after CAM dissociates and the enzyme is autonomously active. Dephosphorylation by PP1 and PP2A returns the enzyme to an inactive state.

Figure \(\PageIndex{12}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of a single subunit of human Ca2+ Calmodulin- Dependent Kinase II Holoenzyme (3SOA)

.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=383&height=351)

The catalytic domain is shown in orange, the association domain in green, and the linker domain in light cyan. The spacefill light cyan site in the linker domain is the CAM binding site. The side chains of Thr 253 and Thr 286, sites for phosphorylation, are shown in spacefill CPK colors and labeled. The side chains of Cys 280 and Met 281, the site for redox regulation, are shown in spacefill CPK colors and labeled. Bosutinib (shown in ball and stick) is a small molecule BCR-ABL and src tyrosine kinase inhibitor used for the treatment of chronic myelogenous leukemia. It is bound in the ATP binding site of the catalytic subunit. Finally, the activation loop is shown in red.

Figure \(\PageIndex{13}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of Human Ca2+ Calmodulin- Dependent Kinase II Holoenzyme (3SOA)

.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=364&height=308)

The response of most protein kinases we have studied depends on the concentration (amplitude) of a binding ligand (like Ca2+). The CAMKII dodecamer also responds to the frequency of Ca2+ waves or spikes as it is released from intracellular organelles. This is important in neurons where CAMKII phosphorylates ion channels that control and regulate neuron response. If the frequency of Ca2+ spikes reaches a certain threshold level, the enzyme no longer depends on Ca2+.

Modeling of Ca2+ signaling

Model for signal-induced Ca2+ oscillations and their frequency encoding through protein phosphorylation.

Reference paper: ALBERT GOLDBETER, GENEVIVE DUPONT, AND MICHAEL J. BERRIDGE , Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, Vol. 87, pp. 1461-1465, February 1990, Biophysics

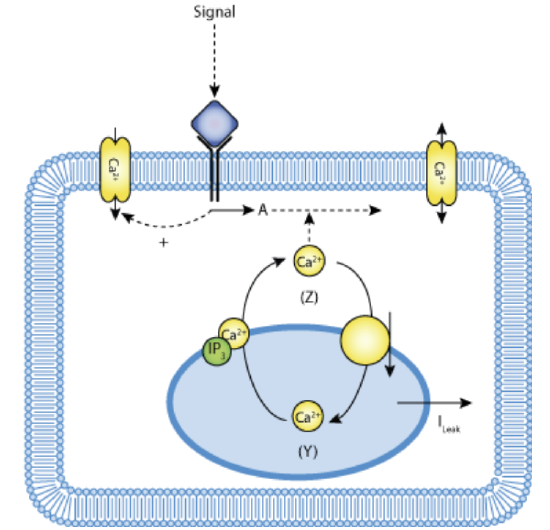

HVJ: In response to hormones and neurotransmitters, cyclic intracellular oscillations/spikes (as a function of time) and spatial waves of cytoplasmic Ca2+ arise. The Ca2+ ions derive from the opening of cell membrane channels but also, more importantly, from the release and recapture of the ions from intracellular compartments such as the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Signaling through membrane GPCRs can lead to the activation of phospholipase C and the formation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3 or InsP3) as a key second messenger. IP3 can interact with the IP3 receptor on ER membranes, leading to the release of intracellular stores of Ca2+ into the cytoplasm in ways that leads to oscillations in its concentration. These processes are shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{14}\) below.

Figure \(\PageIndex{14}\): Ca2+ oscillations in response to inositol trisphosphate (IP3) increase, with and without Ca2+ influx from extracellular space. Catacuzzeno L, Franciolini F. Role of KCa3.1 Channels in Modulating Ca2+ Oscillations during Glioblastoma Cell Migration and Invasion. Int J Mol Sci. 2018 Sep 29;19(10):2970. doi: 10.3390/ijms19102970. PMID: 30274242; PMCID: PMC6213908. Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Panel (A) bottom shows a drawing illustrating the hormone-based production of IP3 that activates the IP3 receptor to release Ca2+ from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). The biphasic effects of cytosolic Ca2+ on IP3 receptor gating (the basic mechanism for Ca2+ oscillations), whereby Ca2+ modulates positively the receptor at low [Ca2+] but negatively at high [Ca2+], is also illustrated. Top, Ca2+ oscillations as produced from the schematics below. Note the decaying trend of Ca2+ spikes due to the absence of Ca2+ influx from extracellular space;

Panel (B) shows Ca2+ influx apparatus from extracellular spaces through ER-depletion by activated Orai channels on the plasma membrane (bottom), which generates sustained Ca2+ oscillations (top).

Ca2+ levels fall through Ca2+ pumps on the sarco/endoplasmic reticulum (SERCA), which moves the ion into the SR/ER or the plasma membrane (PMCA) that then moves it to the outside of the cell. The SERCA and PMCA Ca2+ pumps as well as the ER STIM protein are not shown in Figure 14 above. The STIM1 protein is involved in what is known as store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE). This allows the influx of Ca2+ influx after intracellular stores are depleted. The STIM1 protein has an EF-hand so it binds and acts as a sensor for Ca2+. When Ca2+ is depleted, the STIM1 protein moves from the ER to the cell membrane and activates ORA1, a subunit of the Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ (CRAC) channel to promote Ca2+ into the cell.

In a variety of cells, hormonal or neurotransmitter signals elicit a train of intracellular Ca2+ spikes. The analysis of a minimal model based on Ca2+ -induced Ca2+ release from intracellular stores shows how sustained oscillations of cytosolic Ca2+ may develop as a result of a rise in inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (InsP3) triggered by external stimulation. This rise elicits the release of a certain amount of Ca2+ from an InsP3-sensitive intracellular store. The subsequent rise in cytosolic Ca2+ in turn triggers the release of Ca2+ from a second store insensitive to InsP3. The model shows how signal-induced Ca2+ oscillations might be effectively encoded in terms of their frequency through the phosphorylation of a cellular substrate by a protein kinase activated by cytosolic Ca2+.

The release of intracellular Ca2+ release by IP3 can be broken down into 3 steps: β

- agonist binding to GPCRs to activate the Phospholipase C pathway to produce the second messengers IP3 and DAG;

- IP3 induces some Ca2+ release from intracellular stores in the SR/ER. This can be called the Primer Step characterized by a rate V1 to produce cytosolic Ca2+ of concentration [Z] that prime the next step. This step has a rate of v1β.

- released Ca2+induces more Ca2+ release, a self-amplification positive feedback step, which causes the Ca2+ spike.

A simplified view of this model is shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{15}\) below.

Figure \(\PageIndex{15}\): Schematic representation of the one-pool model based on CICR with Ca2+-stimulated degradation of IP3. Lloyd, C.M., Lawson, J.L., Hunter, P.J. and Nielsen, P.F. The CellML Model Repository. Bioinformatics. 2008 September;24(18):2122-2123 (accessed 4/19/23; 5:40 am EDT). Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.

A simple model can be constructed to account for cytosolic Ca2+ fluxes. The steps include

- IP3 causes a triggering a constant flux of Ca2+ into the cytosol, v1β ,to produce cytosolic [Ca2+] = Z (the primer)

- cytosolic Ca2+ flows into an IP3-insensitive sequestered pool (concentration Y) with rate v2 to keep low levels of cytosolic Ca2+

- Spikes arise when the sequestered pool Y releases Ca2+ back into the cytosol at a rate v3 in a process that is activated by cytosolic Ca2+.

Goldbeter at al (Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 87, 1461-1465 (1990) constructed a mathematical model to account for the oscillations/spikes In addition to the parameters mentioned above, they included 3 more:

- vo, describing the influx of extracellular Ca2+ into the cytosol and k describing the efflux of cytosolic Ca2+ from the cell. These are controlled by Ca2+ pumps SERCA, PMCA, et al as described above.

- kf, which describes the passive leak of Y into Z.

The Ca2+ oscillations then are based on a self-amplified release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores.

Here are their equations:

- \( dZ/dt=v_{0}+v_{1}beta - v_{2}+v_{3}+k_{f}Y-kZ \)

- \( dY/dt=v_{2}-v_{3}+v_{3}-k_{f}Y \)

- \(v_{2}=V_{m2}\frac{Z^{n}}{K^{n}_{2}+Z^{n}} \)

- \(v_{3}=V_{m3}\frac{Y^{m}}{K^{m}_{R}+Y^{m}}.\frac{Z^{p}}{K^{p}_{A}+Z^{p}} \)

We'll use Vcell to plot the following species:

-

Species Z: Concentration (uM) of cytosolic Ca2+

-

Species Y: Concentration (uM) of Ca2+ stored in the InsP3-insensitive pool.

The model is based on code from EBI-Biomodels: https://www.ebi.ac.uk/biomodels/BIOMD0000000098.

Adjust the parameter sliders below the plot to see how they affect Ca2+ concentrations (Z, Y). The simulator only displays twelve parameters at a time. To choose others, hit the 'Slider' button on the side and chose up to twelve parameters to adjust.

Only two variables, Y and Z, and some intra-connections are required to generate the oscillations, which do NOT required oscillation in the second messenger, IP3. One can imagine that cytosolic Ca2+ oscillations might also elicit oscillatory activity of protein kinases activated by it.

Questions:

-

Does v0 change the oscillation frequency?

-

What other parameters affect the frequency?

-

How does Vm2 affect the oscillations?