18.3: Nitrogen Excretion and the Urea Cycle

- Page ID

- 15033

The Urea Cycle

Now we are in a position to see what happens to excess NH3/NH4+ that accumulates in the liver mitochondria. The ammonia that is formed in the liver through oxidative deamination by glutamate dehydrogenase, ends up in urea. Alternatively, it could be added to glutamic acid to form glutamine which can head to the kidney where, after sequential reactions by glutaminase (a deamidation reaction) and glutamate dehydrogenase, it forms ammonia for direct excretion in the urine. If your diet is high in proteins and hence amino acids, since they can't be stored as proteins per se, they are metabolized for energy and the metabolic products can be converted to fat or carbohydrate. That leaves excess nitrogen which ends up mostly as urea for excretion.

Urea is a very water soluble, nontoxic molecule that biochemists use in the lab to chemically denature protein (at concentrations of 3-6 M). Clinical blood urea concentrations are expressed as Blood Urea Nitrogen (BUN) which range from 7 to 20 mg/dL N, which is equivalent to 2.5 to 7.1 mM urea. Serum levels depend predominately on the balance between urea synthesis in the liver and its elimination by the kidney. Normal cellular urea concentrations should be similar.

Urea is produced by a pathway called the urea cycle, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\).

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): The Urea Cycle

The enzyme names are:

- CPS1: carbamoyl phosphate synthase I

- OTC: ornithine transcarbamoylase

- ASS1: arginosuccinate synthase 1

- ASL: arginosuccinase lysase (aka arginosuccinase)

- ARG1: arginase

It is color-coded to designate the sources of the C and N atoms. One N comes from ammonia (or indirectly from the amido N of glutamine), while the C atom comes from carbonate. The other comes from the amine of aspartate. Note that 3 ATPs are used to power the cycle. Also note the guanidino group of arginine (NH(NH2+)NH2) is the immediate donor of the 2 N atoms in the step that produces urea. Knowing that one amino acid was the immediate donor of the N atoms in urea, you would easily predict that.

Now, let's look at some of the steps, starting with the ones that are powered by ATP, which are also the ones where nitrogen is incorporated into the precursors of urea.

Carbamoyl phosphate synthase I (CPS I)

This enzyme catalyzes the first "committed" path of the pathway and makes the reactant that enters the cycle, carbamoyl phosphate. It requires a specific cofactor, N-acetyl-glutamate (NAG), produced by the acetylation of glutamate by acetyl-CoA using an enzyme NAG synthase which is activated by arginine. The reaction is not part of the cycle but provides the input for it.

A cytosolic version of this enzyme, CPS II, is used to synthesize arginine and pyrimidine nucleotides using glutamine as a donor of NH4+which reacts with carboxyphosphate to produce carbamoyl phosphate. It is not regulated by NAG.

CPS I provides a way to form a (C=O)NH2 unit for urea by condensing bicarbonate and ammonia to form a carbamate, which contains a high energy "motif" with respect to its hydrolysis product. (Note: this does not imply that the broken bond is high energy, a misnomer found in many books.) Hence the reaction is powered by 2 ATPs as an energy source. Urea is a molecule that "carries" both NH3/NH4+ and also carbonate.

A reaction mechanism for carbamoyl phosphate synthase is shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\).

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): Reaction mechanism for carbamoyl phosphate synthase

The two high-energy motif molecules (again with respect to their hydrolysis products) are protected from nonspecific hydrolysis as the mixed anhydride pass along a sequestered tunnel to a more distal phosphorylation site in the multimeric enzyme.

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of the human carbamoyl phosphate synthetase I with bound ADP and N-acetyl-glutamate (5DOU).

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): Human carbamoyl phosphate synthetase I with bound ADP and N-acetyl-glutamate (5DOU). (Copyright; author via source). Click the image for a popup or use this external link: https://structure.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/i...yV8fW3mW9idy6A

The model shows one chain of the multimer. The 2 ADPs and single N-acetylglutamate (NLG) are shown in spacefill and labeled. Additional bound ions are shown (unlabeled).

The protein exists in a monomer-dimer equilibrium mixture. Each monomer has 1 NAG and 2 ADP, which represent the two different binding sites for the two different phosphorylation steps as shown in the reaction above. The two phosphorylation sites are connected by a tunnel allowing passage of the mixed anhydride to the carbamate phosphorylation site. The NAG is an allosteric modifier as it is not bound near the phosphorylation sites. On binding to the apo form of the enzyme, it elicits a large conformation change allowing a competent enzyme conformation with a complete tunnel to predominate.

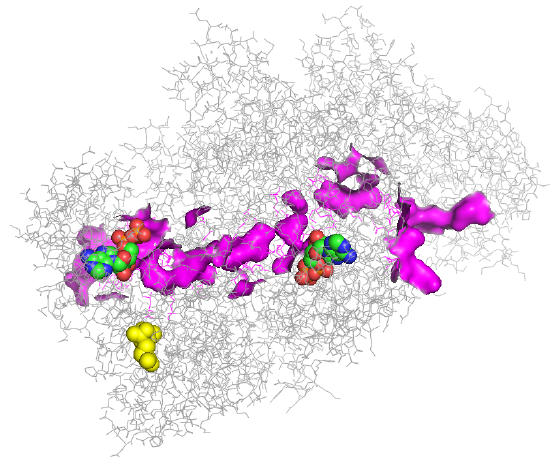

An image of the tunnel for one monomer of the human carbamoyl phosphate synthetase I is shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\).

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\): Tunnel for one monomer of the human carbamoyl phosphate synthetase I enzyme.

Two ADPs are shown below in spacefill with CPK color. The tunnel between the two ADP sites is highlighted in magenta. The yellow molecule is NAG, which again exerts its activation effect by binding to an allosteric site, which effectively opens up the tunnel.

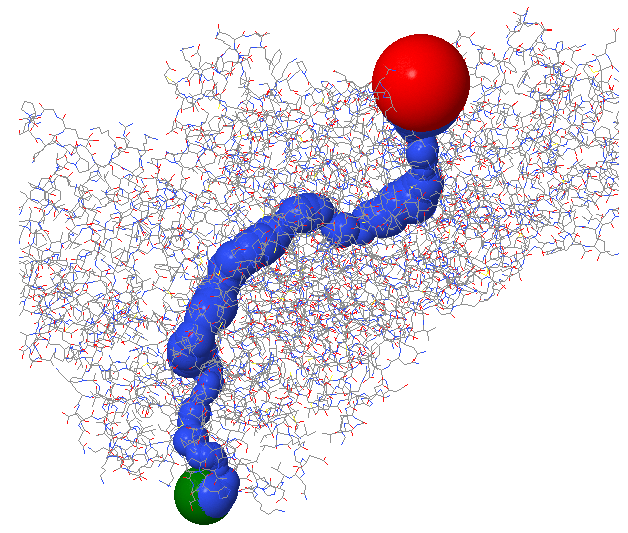

Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\) shows the enzyme monomer in a different orientation with a tunnel made using ChExVis: a tool for molecular channel extraction and visualization. The large red and green spheres show the surface openings.

Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\): Second view of the tunnel in human carbamoyl phosphate synthetase I

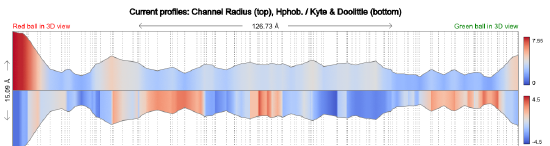

The top panel in Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\) shows the radius in Angstroms of the tunnel going from the Red sphere to the Green sphere in the image above. The bottom panel shows a measure of the hydrophobicity (red)/hydrophilicity (blue) of the amino acids surrounding the tunnel.

Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\): Tunnel size and polarity profile in human carbamoyl phosphate synthetase I

ASS1: ArginoSuccinate Synthase 1

Another ATP is cleaved to drive the conversion of citrulline to arginosuccinate, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\). The product could easily be cleaved in the next step to form the amino acid arginine.

Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\): ATP cleavage drives the conversion of citrulline to arginosuccinate

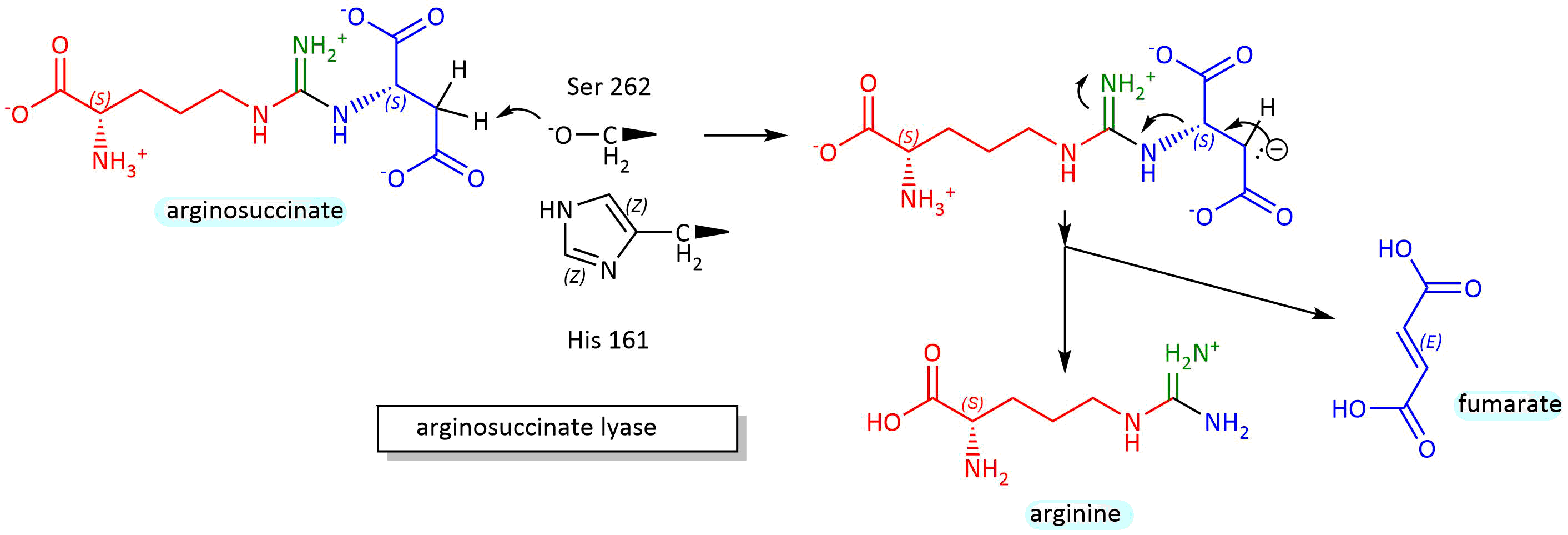

ASL: arginosuccinase lysase (aka arginosuccinase)

This enzyme catalyzes a beta-elimination reaction, which may proceed through either an E2 or E1 mechanism. A general but very abbreviated mechanism showing a two-step (E1) elimination proceeding through a carbanion intermediate is shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\): below.

Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\): Mechanism for conversionof arginosuccinate to arginine and fumarate

Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of the tetrameric arginosuccinate lyase (ASL) from Mycobacterium tuberculosis (6IEN).

Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\): Tetrameric arginosuccinate lyase (ASL) from Mycobacterium tuberculosis (6IEN). (Copyright; author via source). Click the image for a popup or use this external link: https://structure.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/i...32EuouGQ6xMVk6

Each monomer of the four monomers is shown in a different color. 3 arginosuccinates (substrate) and 1 fumarate and 1 arginine (products) are shown in spacefill, with CPK colors and labeled. Each monomer has an N-, M-, and a C-domain. The four binding sites consist of residues from three monomers. The products are in the fourth site. Catalytic residues probably include a serine and histidine act as general acids/bases with a deprotonated lysine making the serine a general base.

Ornithine Transcarbamyolase

The reaction mechanism here is quite simple. The carbamoyl phosphate is an activated electrophile in which the carbonyl C is attacked by a deprotonated amino of ornithine to produce citrulline. The gene is found on the X chromosome in humans so mutations in males lead to a "hyperammonemic coma" and death. Heterozygous females can be asymptomatic and that generally proves to be fatal. Heterozygous females are either asymptomatic or have problems arising from defects in pyrimidine biosynthesis which a low-protein diet can alleviate with the addition of arginine.

Arginase

There are two general variants of this enzyme, Arginase I is a cytosolic enzyme expressed in the liver and is involved in urea synthesis. Arginase II is a mitochondrial enzyme and is involved more generally in arginine metabolism. Arginase I converts arginine to ornithine and urea. The enzyme has 2 Mn ions in the active site. A hydroxide ion bridges the two Mn ions and acts as a nucleophile which attacks the guanidino group of arginine and forms a tetrahedral intermediate. An active site Asp 128 acts as a general acid and protonates the amino leaving group to form ornithine and urea. Water then adds back to the Mn dinuclear cluster and ionizes, donating a proton to solvent through an intermediary His 41 as it reforms the active enzyme.

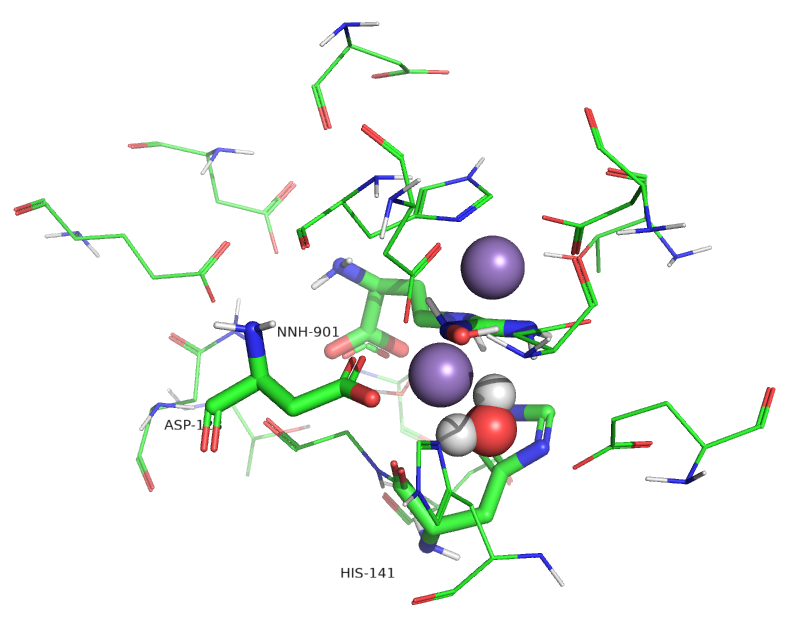

The model below shows the trimeric human arginase I (3KV2) in complex with the inhibitor N(omega)-hydroxy-nor-L-arginine, in which one of the guanidino Ns is replaced with an OH. The two grey spheres are Mn ions.

Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of the trimeric human arginase I in complex with the inhibitor N(omega)-hydroxy-nor-L-arginine (3KV2).

Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\): Trimeric human arginase I in complex with the inhibitor N(omega)-hydroxy-nor-L-arginine (3KV2). (Copyright; author via source). Click the image for a popup or use this external link: https://structure.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/i...QaAQpt5t2KKic6

Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\) show an active site water (#480) near the Mn ions.

Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\): Active site of human arginase I with an active site water

Water molecules can act as ligands and bind transition state metal ions through a coordinate covalent bond. The pKa of the bound water shifts to a lower value, making it more likely to deprotonate to form OH-, which is both a better base and nucleophile. Water 480 in the active site appears to form a coordinate covalent bond to the Mn ion forming an active site hydroxide that attacks the guanidino group of arginine, leading to the formation of urea and ornithine.

Regulation

If excess amino acids/proteins are consumed, a change in gene expression can increase levels of the enzymes in the urea cycle. In the short term, the activity is regulated by the enzyme that provides access into the cycle, carbamoyl phosphate synthase, whose activity is regulated by N-acetylglutamic acid and which catalyzes the rate-limiting step. As shown above, without the allosteric regulator, NAG, the enzyme is functionally inactive. The levels of NAG are determined by the enzyme NAG synthase, which itself is regulated by free arginine, the immediate precursor of urea in the cycle. Supplemental arginine is given to patients with urea disorder system and its effect probably occurs through the regulation of NAG synthase.

The link between the urea cycle and the TCA cycle

Two of the major pathways you have explored, the TCA and urea cycles, are not linear but cyclic pathways. What advantages do "circular" offer over linear ones? Perhaps a comparison to economic pathways offers a clue. In a linear economy, raw materials are used to produce a product which is eventually discarded as trash. Unfortunately, linear pathways dominate our world at a great cost to our environment. To reduce the inefficiencies in a linear economy and make it more viable and to decrease environmental damage and associated climate change, the world should move to a circular economy. A circular economy is characterized by what has been referred to as the 3Rs: reduce, reuse, and recycle. This saves resources and energy. These characteristics also apply to circular biochemical pathways as reduced levels of metabolites get reused and recycled.

Given this, it should not come as a surprise that the urea and TCA cycle are linked, especially given that fumaric acid is a product of the urea cycle and a cyclic metabolite of the TCA cycle. In addition, aspartic acid is one transamination step away from oxaloacetate. The interconnections between the urea cycle and the TCA cycle are shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{12}\) along with two additions, the malate aspartate shuttle, and the aspartate arginosuccinate shunt.

Figure \(\PageIndex{12}\): Urea and TCA cycles linked by the malate aspartate shuttle and the aspartate arginosuccinate shunt.

One of the nitrogens in urea comes from the amine of aspartate, which can be formed through the transamination of oxaloacetate from the TCA cycle to form aspartate. Since the TCA cycle is a cycle, an equivalent of one oxaloacetate must return to the cycle. It does so indirectly from fumarate, a TCA intermediate produced as a by-product of the urea cycle, but the fumarate is produced in the cytoplasm. There, it gets converted to malate, which can get transported into the mitochondria by a transport protein, mitochondrial 2-oxoglutarate/malate transporter, that is part of yet another cycle shown in the figure above, the aspartate arginosuccinate shunt. The introduction of fumarate into the shuttle occurs through the aspartate arginosuccinate shunt shown in the figure above. Once malate enters the mitochondrial matrix, it can be directly converted to oxaloacetate.

Note that these linked cycles require the presence of both mitochondrial and cytoplasmic forms of the several enzymes and balances between two key amino acids across the mitochondrial divide, glutamate, and aspartate. One such key enzyme is ASpartate Amino Transferase (AST), aka Glutamate Oxaloacetate Transaminase (GOT), named for the reverse reaction of aspartate + α−ketoglutarate ↔ oxaloacetate + glutamate. As mentioned in the previous chapter section, this key enzyme can be found in the blood if the liver is damaged, so its levels are routinely used in medical tests for impaired liver function.

Another key function of the malate aspartate shuttle is to bring into the mitochondria reduced "equivalents" of NADH that are produced in the cytoplasm from glycolysis and fatty acid oxidation. There is no membrane transporter for NAD+ or NADH. Instead, cytoplasmic malate, produced by the cytosolic reduction of oxaloacetate by NADH, can be transported into the matrix which can reform mitochondrial NADH on reconversion to oxaloacetate. The NADH can then be used to power ATP production through mitochondrial electron transport/oxidative phosphorylation pathways.

From an energetic perspective, four phosphoanhydrides bonds in 3 ATP molecules are used to produce one urea molecule. This large energy expenditure is partially compensated for by ATP made from the "fumarate equivalents" that enter the mitochondria through the aspartate arginosuccinate and aspartate arginosuccinate shunts and the passage of NADH through oxidative phosphorylation.

.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=381&height=276)

_from_Mycobacterium_tuberculosis_(6IEN).png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=359&height=387)

-hydroxy-nor-L-arginine_(3KV2).png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=325&height=331)