6.3: Kinetics with Enzymes

- Page ID

- 25227

An enzyme alters the pathways for converting a reactant to a product by binding to the reactant and facilitating the intramolecular conversion of bound substrate to bound product before it releases the product. Enzymes do not affect the thermodynamics of reactions. For reversible reactions (as an example), the equilibrium constant, Keq, is unchanged. What is charged is the rate at which equilibrium is achieved. Enzymes lower the activation energy for bound transition states and change the reaction mechanism.

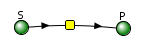

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) shows the simplest chemical reaction that can be written to show how an enzyme catalyzes a reaction.

Rapid Equilibrium Enzyme-Catalyzed Reactions

We have previously derived equations for the reversible binding of a ligand to a macromolecule. Next, we derived equations for the receptor-mediated facilitated transport of a molecule through a semipermeable membrane. This latter case extended the former case by adding a physical transport step. Now, in what hopefully will seem like deja vu, we will derive almost identical equations for the chemical transformation of a ligand, commonly referred to as a substrate, into a product by an enzyme. We will study two scenarios based on two different assumptions, each enabling a straightforward mathematical derivation of kinetic equations:

- Rapid Equilibrium Assumption - enzyme E (macromolecule) and substrate S (ligand) concentrations can be determined using the dissociation constant since E, S, and ES are in rapid equilibrium, as we previously used in our derivation of the equations for facilitated transport. Sorry about the switch from A to S in the designation of the substrate. Biochemists use S to represent the substrate (ligand) and A, B, P, and Q to represent reactants and products in the case of multi-substrate and multi-product reactions.

- Steady State Assumption (more general) - enzyme and substrate concentrations are not those determined using the dissociation constant.

Enzyme kinetics experiments, as we will see in the following chapters, must be used to determine the detailed mechanism of the catalyzed reaction. Using kinetic analysis, you can determine the order of binding/dissociation of substrates and products, the rate constants for individual steps, and clues to the mechanism used by the enzyme in catalysis.

Consider the following reaction mechanism for the enzyme-catalyzed conversion of substrate S into product P. (We will assume that the catalyzed rate is much greater than the noncatalyzed rate.)

\[\ce{E +S <=>[K_s] ES ->[k_3] E + P} \nonumber \]

As we did for the derivation of the equations for the facilitated transport reactions under rapid equilibrium conditions, this derivation is based on the assumption that the relative concentrations of S, E, and ES can be determined by the dissociation constant, KS, for the interactions and the concentrations of each species during the early part of the reaction (i.e. under initial rate conditions). Assume also the S >> E0. Remember that under these conditions, S does not change much with time. Is this a valid assumption? Examine the mechanism shown above. S binds to E with a second-order rate constant k1. ES has two fates. It can dissociate with a first-order rate constant k2 to S + E, or it can be converted to product with a first-order rate constant of k3 to give P + E. If we assume that k2 >> k3 (i.e. that the complex falls apart much more quickly than S is converted to P), then the relative ratios of S, E, and ES can be described by Ks. Alternatively, you can think about it this way. If S binds to E, most of S will dissociate, and a small amount will be converted to P. If it does, then E is now free, and will quickly bind S and reequilibrate since the most likely fate of bound S is to dissociate, not be converted to P (since \(k_3 \ll k_2\)). This also makes sense if you consider that the physical step, characterized by k2, is likely to be quicker than the chemical step, characterized by k3. Hence the following assumptions have been used:

- \(S \gg E_0\)

- \(P_0 = 0\)

- \(k_3\) is rate limiting (i.e. the slow step)

We will derive equations showing the initial velocity v as a function of the initial substrate concentration, S0, assuming that P is negligible over the time period used to measure the initial velocity. Also assume that \(v_{catalyzed} \gg v_{noncatalyzed}\). In contrast to the first-order reaction of S to P in the absence of E, v is not proportional to S0 but rather to Sbound. Therefore, \(v \propto [ES]\), or

\[v = {const} [ES] = k_3 [ES] \label{EQ10} \]

where \(v\) is the velocity (i.e., reaction rate).

Now, let's get \(ES\) from the dissociation constant KS (assuming rapid equilibrium of E, S and ES) and mass balance for E (E0 = E + ES , so E = E0 - ES). We will use mass balance for S when we derive the equation of the steady state. In many cases, S is approximately equal to S0 or the total amount of substrate. This makes sense if you consider that the enzyme is a catalyst acts repeatedly to produce the product, so you don't need significant amounts of the enzyme. The resulting equation of [ES] is shown below.

\begin{equation}

(E S)=\frac{\left(E_0\right)(S)}{K_S+(S)}

\end{equation}

Here it is!

- Derivation

-

\begin{equation}

\begin{gathered}

K_S=\frac{[E][S]}{[E S]}=\left(\frac{\left.\left(\left[E_0\right]-[E S]\right)[S]\right)}{[E S]}\right. \\

(E S) K_S=\left(E_0\right)(S)-(E S)(S) \\

(E S) K_S+(E S)(S)=\left(E_0\right)(S) \\

(E S)\left(K_S+(S)\right)=\left(E_0\right)(S)

\end{gathered}

\end{equation}

This derivation assumes that we know S (which is equal to S0) and Etot (which is E0).

Let us assume that S is much greater than E, as is the likely biological case. We can calculate ES using the following equations and the same procedure we used for the derivation of the binding equation, which gives the equation below:

\begin{equation}

[E S]=\frac{\left[E_0\right][S]}{K_S+S}

\end{equation}

which is analogous to

\begin{equation}

[M L]=\frac{\left[M_0\right][S]}{K_D+L}

\end{equation}

This leads to

\begin{equation}

v_0=\frac{\left(k_3\right)\left(E_0\right)(S)}{K_S+(S)}=\frac{\left(V_M\right)(S)}{K_S+(S)}

\end{equation}

where

\begin{equation}

V_M=k_3 E_0

\end{equation}

This is the world-famous Henri-Michaelis-Menten Equation. It is a hyperbola just like the graph for binding of a ligand to a macromolecule with a given dissociation constant, KD.

Move the sliders in the interactive graph below to see how changing Km and Vm alters the graph. Note that this graph is identical to the graph for M + L ↔ ML.

Just as in the case with noncatalyzed first-order decay, it is easiest to measure the initial velocity of the reaction when [S] does not change much with time and the velocity is constant (i.e. the slope of the dP/dt curve is constant). A plot of [P] vs t (called a progress curve) is made for each different substrate concentration studied. From these curves, the initial rates at each [S] is determined.

Alternatively, one reaction time that gives a linear rise in [P] with time is determined for all the different substrate concentrations. At that specified time, the reaction can be stopped (quenched) with a reagent that does not cause any change in S or P. Then initial rates can be easily calculated for each [S] from a single data point.

Under these conditions:

- a plot of v vs S is hyperbolic

- v = 0 when S = 0

- v is a linear function of S when S<<Ks.

- v = Vmax (or VM) when S is much greater than Ks

- S = KS when v = VM/2.

These are the same conditions we detailed for our understanding of the binding equation

\begin{equation}

(M L)=\frac{\left(M_0\right) L}{K_D+L}

\end{equation}

Note that when S is not >> KS, the graph does not reach saturation and does not look hyperbolic. It should be apparent from the graph that only if S >> KS (or when S is approximately 100 x > Ks) will saturation be achieved.

The KS constant is usually called the Michaelis constant, KM. We will see in a bit that the KM for most enzyme-catalyzed reactions is not equal to the dissociation constant for ES, which we called KS.

Very often, these graphs are transformed into double reciprocal or Lineweaver-Burk plots as shown below.

\begin{equation}

\frac{1}{v_0}=\frac{K_M+S}{V_M S}=\left(\frac{K_M}{V_M}\right) \frac{1}{S}+\frac{1}{V_M}

\end{equation}

These plots are used to estimate VM from the 1/v intercept (1/VM) and KM from the 1/S axis (-1/KM). These values should be used as "seed" values for a nonlinear fit to the hyperbola that models the actual v vs S curve. An interactive graph of 1/v0 vs 1/[S] is shown below. Change the sliders for KM and VM and note the change in the slope and intercepts of the plot

As we saw in the graph of A or P vs t for a noncatalyzed, first-order reaction, the velocity of the reaction, given as the slope of those curves, is always changing. Which velocity should we use in Equation 5? The answer invariably is the initial velocity, v0, measured in the early part of the reaction when little substrate is depleted. Hence v vs S curves for enzyme-catalyzed reactions invariably are really v0 vs [S] curves.

Steady State Enzyme-Catalyzed Reactions

In this derivation, we will consider the following equations and all the rate constants, and will not arbitrarily assume that k2 >> k3. We will still assume that S >> E0 and that P0 = 0. An added assumption, however, is that d[ES]/dt is approximately 0. Look at this assumption this way. When an excess of S is added to E, ES is formed. In the rapid equilibrium assumption, we assumed that it would fall back to E + S (a physical step) faster than it would go onto product (a chemical step). In the steady state case, we will assume that ES might go on to product either less or more quickly than it will fall back to E + S. In either case, a steady state concentration of ES arises within a few milliseconds, and its concentration does not change significantly during the initial part of the reaction under which the initial rates are measured. Therefore, d[ES]/dt is about 0. For the rapid equilibrium derivation, v = k3[ES]. We then solved for ES using KS and mass balance of E. In the steady state assumption, the equation v= k3[ES] still holds, but now we will solve for [ES] using the steady state assumption that d[ES]/dt =0.

\begin{equation}

\frac{d[E S]}{\mathrm{dt}}=\mathrm{k}_1[E][S]-\mathrm{k}_2[E S]-\mathrm{k}_3[E S]=0

\end{equation}

We can solve this and obtain the Michaelis-Menten equation for reaction.

\begin{equation}

\mathrm{v}=\mathrm{k}_3[\mathrm{ES}]=\frac{\mathrm{k}_3\left[\mathrm{E}_0\right][\mathrm{S}]}{\frac{\mathrm{k}_2+\mathrm{k}_3}{\mathrm{k}_1}+\mathrm{S}}=\frac{\mathrm{V}_{\mathrm{M}}[\mathrm{S}]}{\mathrm{K}_{\mathrm{M}}+\mathrm{S}}

\end{equation}

To see how to derive this, click below.

- Answer

-

Applying mass balance for E (i.e E = E0-ES) in appropriate term below gives

\begin{array}{l}{\mathrm{k}_{1}[E][S]=\left(\mathrm{k}_{2}+\mathrm{k}_{3}\right)[E S]} \\ {\mathrm{k}_{1}\left[\mathrm{E}_{0}-\mathrm{ES}\right][S]=\left(\mathrm{k}_{2}+\mathrm{k}_{3}\right)[E S]} \\ {\mathrm{k}_{1}\left[\mathrm{E}_{0}\right][S]-\mathrm{k}_{1}[\mathrm{ES}][S]=\left(\mathrm{k}_{2}+\mathrm{k}_{3}\right)[E S]} \\ {\mathrm{k}_{1}\left[\mathrm{E}_{0}\right][S]=\left(\mathrm{k}_{2}+\mathrm{k}_{3}\right)[E S]+\mathrm{k}_{1}[\mathrm{ES}][S]} \\ {\mathrm{k}_{1}\left[\mathrm{E}_{0}\right][S]=[E S]\left(\mathrm{k}_{2}+\mathrm{k}_{3}+\mathrm{k}_{1} \mathrm{S}\right)}\end{array}

Solving for [ES] gives

\begin{equation}

[\mathrm{ES}]=\left(\frac{\left[\mathrm{E}_0\right][\mathrm{S}]}{\frac{\mathrm{k}_2+\mathrm{k}_3}{\mathrm{k}_1}+\mathrm{S}}\right)

\end{equation}Substituting into the Henri Michaelis Menten equation gives

\begin{equation}

\mathrm{v}=\mathrm{k}_3[\mathrm{ES}]=\frac{\mathrm{k}_3\left[\mathrm{E}_0\right][\mathrm{S}]}{\frac{\mathrm{k}_2+\mathrm{k}_3}{\mathrm{k}_1}+\mathrm{S}}=\frac{\mathrm{V}_{\mathrm{M}}[\mathrm{S}]}{\mathrm{K}_{\mathrm{M}}+\mathrm{S}}

\end{equation}

Note that

\begin{equation}

V_M=k_3 E_0

\end{equation}

and

\begin{equation}

K_M=\frac{k_2+k_3}{k_1}

\end{equation}

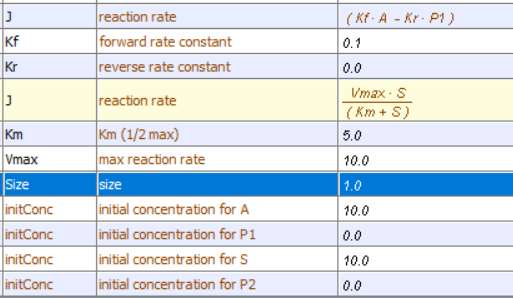

Now let's look at a progress curve simulation that compares the Michaelis-Menten equation derived from rapid equilibrium assumptions (when k2>>k3) and in which KM is the actual dissociation constant to the steady state approximation, when k2 is not >>k3. Reaction 1 is the rapid equilibrium and Reaction 2 the steady state.

The initial conditions in the graph are set so the graphs of the rapid equilibrium and steady state are identical.

Recommendations:

- Scale the y-axis to 50

- change the slider k2_r2 for the steady state graph to other values. Watch the curves separate. Although these plots are only for 1 substrate concentration (50 uM), the effects of changing k2 for the steady state plot are very dramatic. This should convince you that in general, unless k3 << k2, the calculated value of KM is not equal to the thermodynamic dissociation constant, KD.

Analysis of the General Michaelis-Menten Equation

This equation can be simplified and studied under different conditions. First, notice that (k2 + k3)/k1 is a constant which is a function of relevant rate constants. This term is usually replaced by KM which is called the Michaelis constant. Likewise, when S approaches infinity (i.e. S >> KM, equation 5 becomes v = k3(E0) which is also a constant, called VM for maximal velocity. Substituting VM and KM into equation 5 gives the simplified equation:

\begin{equation}

\mathrm{v}=\frac{\mathrm{V}_{\mathrm{M}}[\mathrm{S}]}{\mathrm{K}_{\mathrm{M}}+\mathrm{S}}

\end{equation}

It is extremely important to note that KM in the general equation does not equal the KS, the dissociation constant used in the rapid equilibrium assumption! KM and KS have the same units of molarity, however. A closer examination of KM shows that under the limiting case when k2 >> k3 (the rapid equilibrium assumption) then,

\begin{equation}

\mathrm{K}_{\mathrm{M}}=\frac{\mathrm{k}_2+\mathrm{k}_3}{\mathrm{k}_1}=\frac{\mathrm{k}_2}{\mathrm{k}_1}=\mathrm{K}_{\mathrm{D}}=\mathrm{K}_{\mathrm{S}}

\end{equation}

If we examine these equations under several different scenarios, we can better understand the equation and the kinetic parameters:

- when S = 0, v = 0.

- when S >> KM, v = VM = k3E0. (i.e. v is zero order with respect to S and first order in E. Remember, k3 has units of s-1> since it is a first-order rate constant. k3 is often called the turnover number, because it describes how many molecules of S "turn over" to product per second.

- v = VM2, when S = KM.

- when S << KM, v = VMS/KM = k3E0S/KM (i.e. the reaction is bimolecular, dependent on both on S and E. k3/KM has units of M-1s-1, the same as a second order rate constant.

More Complicated Enzyme-catalyzed Reactions

A reversibly-catalyzed reaction

You have learned previously that enzymes don't change the equilibrium constant for a reaction, but rather lowers the activation energy barrier to move from reactants to products. This implies that the activation energy to move in the reverse direction, from products to reactants, is also lowered. Hence the enzyme speeds up both the forward and reverse reaction. We haven't accounted for that yet in our kinetic equations. Many reactions in metabolic reactions that do not have large negative values of ΔG (ie. they are not significantly favored) are reversible, allowing the enzyme to be used in the reverse direction. Take for example the pathway to break down glucose to pyruvate (glycolysis). It has 9 different steps, of which 5 are reversible, allowing them to be used in the reverse pathway to take pyruvate to glucose (gluconeogenesis).

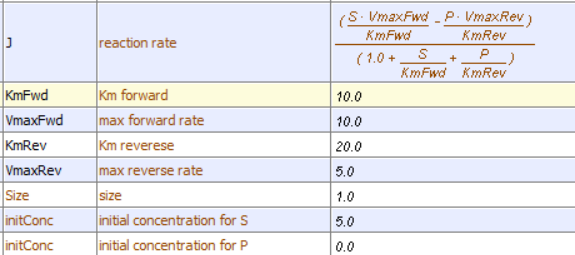

Let's set up the equations for the reversible reaction of substrate S to product P catalyzed by enzyme E. Assume that the KM for the forward reaction is KMS (or KS) and for the reverse reaction is KMP (or KP) as shown in the reaction scheme in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\). The rate constant k2 is the kcat (forward rate constant) for conversion of ES to EP and k-2 is the kcat (reverse rate constant) for conversion of EP to ES

The following simple Michaelis-Menten equations can be written for just the forward reaction and for the reverse reaction:

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

&v_f=\frac{V_f S}{K_{M S}+S}=\frac{\frac{V_f S}{K_{M S}}}{1+\frac{S}{K_{M S}}} \\

&v_r=\frac{V_r P}{K_{M P}+P}=\frac{\frac{V_r P}{K_{M P}}}{1+\frac{P}{K_{M P}}}

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}

Now you might think that simply substracting the two would give the net velocity in the forward direction, but that is NOT the case.

\begin{equation}

v \neq\left[\frac{\frac{V_f S}{K_{M S}}}{1+\frac{S}{K_{M S}}}-\frac{\frac{V_r P}{K_{M P}}}{1+\frac{P}{K_{M P}}}\right]

\end{equation}

The reason is that in the derivation, the equations for both the forward and reverse rates must have terms for the reverse and forward reactions, respectively.

A simple derivation shows that this is the equation for the reversible conversion of substrate to product.

\begin{equation}

v=k_2[E S]-k_{-2}[E P]=\frac{V_f \frac{[S]}{K_S}}{\left[1+\frac{[S]}{K_S}+\frac{[P]}{K_p}\right]}-\frac{V_r \frac{[P]}{K_P}}{\left[1+\frac{[S]}{K_S}+\frac{[P]}{K_P}\right]}=\frac{V_f \frac{[S]}{K_S}-V_r \frac{[P]}{K_P}}{\left[1+\frac{[S]}{K_S}+\frac{[P]}{K_P}\right]}

\end{equation}

This reversible form of the Michaelis-Menten equation and other equations, written in the format shown in equation 6.24, are commonly used in programs such as VCell and Copasi to model the kinetics of whole pathways of biological interactions and reactions. The figures below show a reaction diagram, graphical results showing S and P vs time for the selected KM and VM values shown, and animations for the reaction. The chemical (S and P) are shown as green spheres connected by a line. The red dot again represents the enzyme (shown as a node of connection between S and P). Equation 6.24 was used to model the reversible reaction (even though the arrows shown between S and P are unidirectional.

If you reflect on it, this reaction is very similar to the reversible reaction of A ↔ P in the absence of an enzyme, which we explored in Chapter section 6.2. Just for comparison, the graph for that reaction is shown below. Change the sliders to produce a curve similar to the enzyme-catalyzed reaction shown in the figure above.

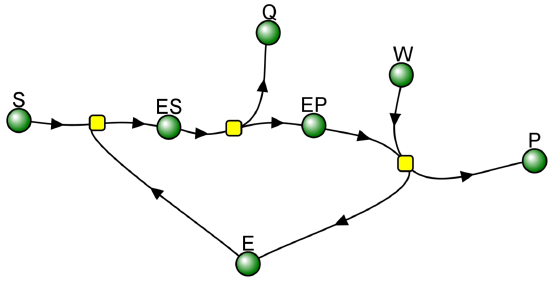

Reaction with intermediates

Not all reactions can be characterized so simply as a simple substrate interacting with an enzyme to form an ES complex, which then turns over to form product. Sometimes, intermediates form. For example, a substrate S might interact with E to form a complex, which then is cleaved to products P and Q. Q is released from the enzyme, but P might stay covalently attached. This happens often in the hydrolytic cleavage of a peptide bond by a protease, when an activated nucleophile like Ser reacts with the sessile peptide bond in a nucleophilic substitution reaction, releasing the amine end of the former peptide bond as the leaving group while the carboxy end of the peptide bond remains bonded to the Ser as an Ser-acyl intermediate. Water then enters and cleaves the acyl intermediate, freeing the carboxyl end of the original peptide bond. This is shown in the written reaction in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\):

Even for this seemingly complicated reaction, you get the standard Michaelis-Menten equation.

To simplify the derivation of the kinetic equation, let's assume that E, S, and ES are in rapid equilibrium defined by the dissociation constant, Ks. Assume Q has a visible absorbance, so it is easy to monitor. Assume from the steady state assumption that:

\begin{equation}

\frac{\mathrm{d}[\mathrm{E}-\mathrm{P}]}{\mathrm{dt}}=\mathrm{k}_2[\mathrm{ES}]-\mathrm{k}_3[\mathrm{E}-\mathrm{P}]=0

\end{equation}

assuming that k3 is a pseudo first-order rate constant and that [H2O] doesn't change.

The velocity depends on which step is rate-limiting. If k3<<k2, then the k3 step is rate-limiting. Then

\begin{equation}

\mathrm{v}=\mathrm{k}_3[\mathrm{E}-\mathrm{P}]

\end{equation}

If k2<<k3, then the k2 step is rate-limiting. Then

\begin{equation}

\mathrm{v}=\mathrm{k}_2[\mathrm{ES}]

\end{equation}

The following kinetic equation for this reaction can be derived, assuming v = k2[ES].

\begin{equation}

\mathrm{v}=\frac{\frac{\mathrm{k}_2 \mathrm{k}_3}{\mathrm{k}_2+\mathrm{k}_3}\left[\mathrm{E}_0\right][\mathrm{S}]}{\left(\frac{\mathrm{k}_3}{\mathrm{k}_2+\mathrm{k}_3}\right) \mathrm{K}_{\mathrm{S}}+\mathrm{S}}=\frac{\mathrm{k}_{\mathrm{cat}}\left[\mathrm{E}_0\right][\mathrm{S}]}{\mathrm{K}_{\mathrm{M}}+\mathrm{S}}=\frac{\mathrm{V}_{\mathrm{M}} \mathrm{S}}{\mathrm{K}_{\mathrm{M}}+\mathrm{S}}

\end{equation}

You can verify that you get the same equation if you assume that v = k3[E-P].

This equation looks quite complicated, especially if you substitute for Ks, k-1/k1. All the kinetic constants can be expressed as functions of the individual rate constants. However, this equation can be simplified by realizing the following:

- When \(\mathrm{S}>>\frac{\mathrm{K}_{\mathrm{S}} \mathrm{k}_{3}}{\mathrm{k}_{2}+\mathrm{k}_{3}}, \mathrm{v}=\left(\frac{\mathrm{k}_{2} \mathrm{k}_{3}}{\mathrm{k}_{2}+\mathrm{k}_{3}}\right) \mathrm{E}_{0}=\mathrm{V}_{\mathrm{M}}\)

- \(\frac{\mathrm{K}_{\mathrm{S}} \mathrm{k}_{3}}{\mathrm{k}_{2}+\mathrm{k}_{3}}=\mathrm{constant}=\mathrm{K}_{\mathrm{M}}\)

Substituting these into equation 7 gives:

\[\mathrm{v}=\frac{\mathrm{V}_{\mathrm{M}} \mathrm{S}}{\mathrm{K}_{\mathrm{M}}+\mathrm{S}} \nonumber \]

This again is the general form of the Michaelis-Menten equation

The expression for VM in the first bulleted expression above is more complicated than our earlier definition of VM = k3E0. They are similar in that the term E0 is multiplied by a constant which is itself a function of rate constant(s). The rate constants are generally lumped together into a generic constant called kcat.

- For the simple reaction kcat = k3

- For the more complicated reaction above with a covalent intermediate, \(\mathrm{k}_{\mathrm{cat}}=\frac{\mathrm{k}_{2} \mathrm{k}_{3}}{\mathrm{k}_{2}+\mathrm{k}_{3}}\)

- For all reactions, VM = kcatE0.

Recent Updates (2/7/24): Here is a VCell computational model for a bisubsrate and biproduct (BiBi) reaction with a covalent intermediate (ping pong reaction).

In the case when k2 >> k3, Q forms quickly in a burst phase due to a high k2. This phase is followed by the slower conversion of the accumulated EP to E + P in a steady state phase, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) below. Make sure to change the parameters in the model above to best see the burst phase for production of product Q. This reaction is an example of a BiBi (two substrates, two products) Ping Pong reaction, since 1 reactant binds, followed by 1 product departing before the second react binds and the second product departs.

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\): Burst and steady-state phase in an enzyme-catalyzed reaction with a covalent intermediate and k2 >> k3.

Reverse the rate constants in the model to k2 = 5 and k3 = 0.5 so that k2 is not >> k3 and note that the burst phase for Q disappears!

When plotting v0 vs S Michaelis-Menten plots of this type of reaction, the state state v0 should be used and NOT (v0) t=0 = (dQ/dt) t=0, since that rate changes very quickly after the initial burst formation of Q.

Summary

Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\) compares the Michaelis-Menten kinetic equations for the rapid equilibrium, steady state assumptions, and covalent intermediate cases .

Meaning of Kinetic Constants

It is important to get a "gut-level" understanding of the significance of the rate constants. Here they are:

- KM: The Michaelis constant with units of molarity (M), is operationally defined as the substrate concentration at which the initial velocity is half of VM. It is equal to the dissociation constant of E and S only in if E, S and ES are in rapid equilibrium. It can be thought of as an "effective" (but not actual) KD in other cases.

- kcat: The catalytic rate constants, with units of s-1 is often called the turnover number. It is a measure of how many bound substrate molecules "turnover" or form product in 1 second. This is evident from equation v0 = kcat[ES]

- kcat/KM: Under condition when [S] << KM, the Michaelis-Menten equation becomes v0 = (kcat/KM)[E0][S]. This really describes a biomolecular rate constant (kcat/KM), with units of M-1s-1, for conversion of free substrate to product. Some enzymes have kcat/Km values around 108, indicating that they are diffusion controlled. That implies that the reaction is essentially done as soon as the enzyme and substrate collide. The constant kcat/Km is also referred to as the specificity constant in that it describes how well an enzyme can differentiate between two different competing substrates. (We will show this mathematically in the next chapter.)

Table \(\PageIndex{1}\) below shows KM and kcat values for various enzymes

| KM values | ||

| enzyme | substrate | Km (mM) |

| catalase | H2O2 | 25 |

| hexokinase (brain) | ATP | 0.4 |

| D-Glucose | 0.05 | |

| D-Fructose | 1.5 | |

| carbonic anhydrase | HCO3- | 9 |

| chymotrypsin | glycyltyrosinylglycine | 108 |

| N-benzoyltyrosinamide | 2.5 | |

| b-galactosidase | D-lactose | 4.0 |

| threonine dehydratase | L-Thr | 5.0 |

| kcat values | ||

| enzyme | substrate | kcat (s-1) |

| catalase | H2O2 | 40,000,000 |

| carbonic anhydrase | HCO3- | 400,000 |

| acetylcholinesterase | acetylcholine | 140,000 |

| b-lactamase | benzylpenicillin | 2,000 |

| fumarase | fumarate | 800 |

| RecA protein (ATPase) | ATP | 0.4 |

Table \(\PageIndex{1}\): KM and kcat values for various enzymes

Table \(\PageIndex{2}\) below show kcat, KM and kcat/KM values for diffusion-controlled enzymes

| Enzymes with kcat/KM values close to diffusion controlled (108 - 109 M-1s-1) | |||||

| enzyme | substrate | kcat (s-1) | Km (M) | kcat/Km (M-1s-1) | |

| acetylcholinesterase | acetylcholine | 1.4 x 104 | 9 x 10-5 | 1.6 x 108 | |

| carbonic anhydrase | CO2 | 1 x 106 | 1.2 x 10-2 | 8.3 x 107 | |

| HCO3- | 4 x 105 | 2.6 x 10-2 | 1.5 x 107 | ||

| catalase | H2O2 | 4 x 107 | 1.1 | 4 x 107 | |

| crotonase | crotonyl-CoA | 5.7 x 103 | 2 x 10-5 | 2.8 x 108 | |

| fumarase | fumarate | 8 x 102 | 5 x 10-6 | 1.6 x 108 | |

| malate | 9 x 102 | 2.5 x 10-5 | 3.6 x 107 | ||

| triose phosphate isomerase | glyceraldehyde-3-P | 4.3 x 103 | 4.7 x 10-4 | 2.4 x 108 | |

| b-lactamase | benzylpenicillin | 2.0 x 103 | 2 x 10-4 | 1 x 108 | |

Table \(\PageIndex{2}\) below show kcat, KM and kcat/KM values for diffusion controlled enzymes

Experimental Determination of VM and KM

How can VM and KM be determined from experimental data?

From initial rate data

The most common way to determine VM and KM is through initial rates, v0, obtained from P or S vs time curves. Hyperbolic graphs of v0 vs [S] can be fitted or transformed as we explored with the different mathematical transformations of the hyperbolic binding equation to determine KD. These included:

- Michaelis-Menten plot: nonlinear hyperbolic fit

- Lineweaver-Burk double reciprocal plot

- Scatchard plot

- Eadie-Hofstee plot

We discussed all of these plots except for the Eadie-Hofstee plot, in the chapter on binding. The Eadie-Hofstee plot is another linearized version of Michaelis-Menten equation

Here is a derivation of that equation, which starts with each side of the double-reciprocal plot being multiplied by v0VM.

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

\left(v_0 V_M\right) \frac{1}{v_0} &=\left(v_0 V_M\right)\left(\frac{K_M}{V_M}\right) \frac{1}{S}+\left(v_0 V_M\right) \frac{1}{V_M} \\

V_M &=\left(v_0\right) K_M \frac{1}{S}+\left(v_0\right) \\

v_0 &=-K_M\left(\frac{v_0}{S}\right)+V_M

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}

Note that a graph of v0 vs v0/S is linear so slopes and intercepts can be used to obtain values for VM and KM.

The double-reciprocal plot is commonly used to analyze initial velocity vs substrate concentration data. When used for such purposes, the graphs are referred to as Lineweaver-Burk plots, where plots of 1/v vs 1/S are straight lines with slope m = KM/VM, and y-intercept b = 1/VM. Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\) common graphs used to display initial rate enzyme kinetic data.

The straight-line plots shown above should not be analyzed using linear regression, since simple linear regression assumes constant error in v0 values. A weighted linear regression or even better, a nonlinear fit to a hyperbolic equation should be used. (Common Error in Biochemistry Textbooks: The Shape of the Hyperbola). A rearrangement of the corresponding Scatchard equations in the Eadie-Hofstee plot is also commonly used, especially to visualize enzyme inhibition data as we will see in the next chapter.

An Extension:

KM and VM could be theoretically extracted from progress curves of A or P as a function of t at one single A concentration by deriving an integrated rate equation for A or P as a function of t, as we did in equation 2 (the integrated rate equation for the conversion of A → P in the absence of enzyme). In principle, this method would be better than the initial rates methods. Why? It is not easy to be certain you are measuring the initial rate for each and every [S] which should vary over a wide range. It's also time intensive. In addition, think how much data is discarded if you take an entire progress curve at each substrate concentration, especially if you quench the reaction at a given time point, which effectively limits the data to one time point per substrate.

In practice, the mathematics is complicated and it is not possible to get a simple explicit function of [P] or [S] as a function of time. A slight variant of a progress curve can be derived. Let us consider the simple case of a single substrate S (or A) being converted to product P in an enzyme-catalyzed reaction. The analogous equations for first-order, noncatalyzed rates were A=A0e-k1t or P = A0(1-e-k1t).

We can derive the equation for the enzyme-catalyzed reaction shown below.

Here it is!

\begin{equation}

\frac{\mathrm{P}}{\mathrm{t}}=\frac{\mathrm{K}_{\mathrm{M}} \ln \left(\frac{\mathrm{S}_0-\mathrm{P}}{\mathrm{S}_0}\right)}{\mathrm{t}}+\mathrm{V}_{\mathrm{M}}

\end{equation}

Click below to see the derivation

- Derivation

-

\begin{equation}

\begin{array}{r}

\mathrm{v}=-\frac{\mathrm{dS}}{\mathrm{dt}}=+\frac{\mathrm{dP}}{\mathrm{dt}}=\frac{\mathrm{V}_{\mathrm{M}} \mathrm{S}}{\mathrm{K}_{\mathrm{M}}+\mathrm{S}} \\

\int_{\mathrm{S}_0}^{\mathrm{S}} \frac{\mathrm{K}_{\mathrm{M}}+\mathrm{S}}{\mathrm{V}_{\mathrm{M}} \mathrm{S}} \mathrm{d} S=-\int_0^{\mathrm{t}} \mathrm{t}

\end{array}

\end{equation}\begin{equation}

-\mathrm{t}=\frac{\mathrm{S}+\mathrm{K}_{\mathrm{M}} \ln \mathrm{S}-\mathrm{S}_0-\mathrm{K}_{\mathrm{M}} \ln S_0}{\mathrm{~V}_{\mathrm{M}}}

\end{equation}On rearrangement, this gives:

\begin{equation}

\mathrm{S}_0-\mathrm{S}+\mathrm{K}_{\mathrm{M}} \ln \frac{\mathrm{S}_0}{\mathrm{~S}}=\mathrm{V}_{\mathrm{M}} \mathrm{t}

\end{equation}This equation is an implicit equation, not an explicit one, as it does NOT give S(t) explicitly as a function of t.

Equation yy can be written with respect to product P as follows:

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

&P=\mathrm{S}_0-S{ }^{\prime \prime} \text { or }{ }^{\prime \prime} S=\mathrm{S}_0-P \\

&\mathrm{~S}_0-\left(\mathrm{S}_0-\mathrm{P}\right)+\mathrm{K}_{\mathrm{M}} \ln \frac{\mathrm{S}_0}{\mathrm{~S}_0-\mathrm{P}}=\mathrm{V}_{\mathrm{M}} \mathrm{t} \\

&\mathrm{P}-\mathrm{K}_{\mathrm{M}} \ln \left(\frac{\mathrm{S}_0-\mathrm{P}}{\mathrm{S}_0}\right)=\mathrm{V}_{\mathrm{M}} \mathrm{t}

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}Rearranging this gives

\begin{equation}

\frac{\mathrm{P}}{\mathrm{t}}=\frac{\mathrm{K}_{\mathrm{M}} \ln \left(\frac{\mathrm{S}_0-\mathrm{P}}{\mathrm{S}_0}\right)}{\mathrm{t}}+\mathrm{V}_{\mathrm{M}}

\end{equation}

S(t) explicitly as a function of t.

This equation does not give P(t) explicitly as a function of time. Rather one can get a graph of P/t vs [ln (1-P/S0)]/t (shown below) from the derived equation, which does give a straight line with a slope of Km and a y-intercept of Vm. Note that the calculated values of VM and KM are derived from only one substrate concentration, and the values may be affected by product inhibition.

Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\) shows the comparison of a first-order noncatalyzed conversion of A → P to the enzyme-catalyzed rate. The VM for the enzyme-catalyzed reaction was chosen to be small to make the two graph comparable.

Note that the curves are similar but not identical. If you didn't know an enzyme was present, you could fit the data to a first-order rise in [P] with time, but it would not be the optimal fit. The progress curves are a lot more complicated to analyze if the product, which shares structural similarities with the substrate, binds the enzyme tightly and inhibits it (called product inhibition).

Comparison of progress Curves of uncatalyzed and catalyzed reactions.

Let's explore progress curves for enzyme-catalyzed reactions a bit further. Students usually see v0 vs [S] Michaelis-Menten plots in textbooks. These plots are in some ways less intuitive than seeing P vs t curves, which are more in line with how we might contemplate how a reaction proceeds. Hence, it would be illuminating to compare progress curve graphs of A → P (irreversible) for the uncatalyzed and S → P for the enzyme-catalyzed reactions. What might you expect? We saw one example in Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\).

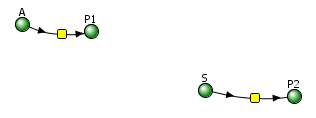

In each case, P should increase with time. In the uncatalyzed reaction, S exponentially decreases to 0 and P concomitantly rises to a value of P = S0. You also get a rise in P vs t for the enzyme-catalyzed rate, but you would think it would be a faster rise with time since the enzyme catalyze the reaction. Figure \(\PageIndex{87}\) shows a comparison of the progress curves for the uncatalyzed first-order reaction of A → P1 (red) and S → P2 (blue) for enzym- catalyzed reaction (blue, right) for these conditions: uncatalyzed reaction A → P1, k1 = 0.1; Catalyzed reaction: S → P2, VM=10, KM=5. Note that the rate at which bound S (i.e ES) goes to P for the catalyzed rate is 100x faster than the rate constant for the catalyzed rate.

Note that the curves are somewhat similar in shape but also clearly different in comparison to the one shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\).

Now let's use Vcell to compare the reactions for different values for the kinetic constants for the uncatalyzed and the enzyme-catalyzed reaction. Change the constants and try to find a set of conditions so that the catalyzed and catalyzed rates for conversion of reactions to products are superimposable. How can that be?

Animations

Now let's look at an animation of the same irreversible reactions in which enzyme-catalyzed reaction is no faster than the noncatalyzed rate (a worthless enzyme!). Here are the reactions:

A→P, k1 =0.1; S → P, VM=?, KM = ?.

The animations show just the accumulation of product. Animations are by Shraddha Nakak and Hui Liu.

Use the Vcell model above to find a set of values for KM and VM that would make the two graphs superimposable - i.e. when the graphs in the absence and presence of E are identical. (Hint: that would be a really bad enzyme if it didn't increase the reaction over the uncatalyzed rate!)

- Answer

-

KM = 96, VM = 10