5.1: Binding - The First Step Towards Protein Function

- Page ID

- 21147

Reversible Binding of a Ligand to a Macromolecule

Reversible, noncovalent binding of two or molecules is the first step in the expression of the biological properties of almost all biomacromolecules. If one of the molecules is small, it's often called a ligand. Ligands are often referred to by other names. Substrates are the reactants that bind to the active sites of enzymes. Hormones and neurotransmitters bind to solution phase or membrane-bound receptor proteins. Metal ions (simple like Ca2+ or molecular like CH3CO2-) are also considered ligands when bound to proteins or nucleic acids.

You might be more familiar with the term ligand when it's applied to the coordination of a transition metal complex by electron pair donors (Lewis acids) on single or multidentate molecules, which for transition metal complexes are called ligands. Here is an interactive molecule model of a cobalt ion binding to EDTA, a multidentate ligand.

The cobalt ion (dark grey ball) is octahedrally-coordinated to the multidentate ligand EDTA.

Whether a macromolecule M and a ligand L bind to each other depends on their relative concentrations and how tightly they bind. Compare this to an acid. Its pKa and the pH of the medium determine if it deprotonates.

Biochemists rarely talk about equilibrium constants to describe the strength of a binding interaction, but rather their reciprocals - the dissociation constants, \(K_D\). For the reactions \(M + L ↔ ML\), where M is free macromolecule, L is free ligand, and ML is macromolecule-ligand complex (which is held together by intermolecular forces, not covalent forces), the KD is given by

\begin{equation}

\left.K_D=[M]_{e q}\right][L]_{e q} /[M L]_{e q}

\end{equation}

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) shows free and bound M and L.

Notice the unit of KD is molarity, M.

- The lower the KD (i.e. the higher the [ML] at any given M and L), the tighter the binding.

- The higher the KD, the looser the binding. KDs for biological molecules are finely tuned to their environments.

KD values vary from about 1 mM (weak interactions) for some enzyme-substrate complex, to pM - fM levels. Examples of very tight, non-covalent interactions include the avidin (an egg protein)-biotin (a vitamin) and thrombin (enzyme initiating clotting)-hirudin (a leech salivary protein) complexes. The values are "tuned" so that the relative concentration of free and bound M and L are appropriate for a biological setting.

To understand binding, it is important not only to know the noncovalent, intermolecular forces (IMFs) that lead to binding, but also to ask the simple question: are the macromolecule and ligand bound? If so, to what extent? To know if M or L is bound, we must use simple mathematics that you would have learned in Introductory or Analytical Chemistry courses. We'll start with the mathematical description which is harder for students to understand than the IMFs.

We will start with three basic equations:

For the Dissociation constant:

\begin{equation}

K_D=([M] e q[L] e q) /[M L] e q=([M][L]) /[M L]

\end{equation}

(note that KD has units of molarity);

For Mass Balance of M:

\begin{equation}

M_0=M+M L

\end{equation}

where M0 is the total amount of macromolecule. (note: brackets and the eq subscript will be left off if the resulting equation is nonambiguous)

For Mass Balance of L:

\begin{equation}

L_0=L+M L

\end{equation}

where L0 is the total amount of ligand

We would like to derive equations which give ML as a function of known or measurable values. The KD equation (5.1) shows

that ML depends on free M and free L. From the equations above we can two derive two fundamental and equally valid equations which are useful under different experimental conditions.

Case 1:

This applies when you can readily measure free L OR when experimental conditions are such the Lo >> Mo (so L= Lo), which is often encountered in a lab setting. You don't have to measure free L since, for this case, it is approximately the total ligand that was added to the system.

Substitute 5.1.3 into 5.1.1 gives

\begin{equation}

\begin{gathered}

\left.K_D=([M][L]) /[M L]=[M o-M L][L]\right) /[M L \\

(M L) K_D=\left(M_o\right) L-(M L) L \\

(M L) K_D+(M L) L=\left(M_o\right) L \\

(M L)\left(K_D+L\right)=\left(M_0\right) L

\end{gathered}

\end{equation}

or

\begin{equation}

(M L)=\frac{\left(M_0\right) L}{K_D+L}

\end{equation}

This equation is ALWAYS TRUE for the chemical equation written above. L is the free ligand concentration at equilibrium.

An interactive plot of the concentration of the ML complex (ML) vs free L (L) is shown below. Vary the sliders and note the changes in the graph.

If L0 >> M0, then the equations simplify to:

\begin{equation}

M L=\frac{\left(M_0\right)\left(L_0\right)}{K_D+L}

\end{equation}

Dividing this equation by Mo gives the fractional saturation Y of the macromolecule M.

\begin{equation}

Y=[M L] / M_0=\frac{L}{K_D+L}

\end{equation}

where Y can vary from 0 (when L = 0) to 1 (when L >> KD)

Note that the interactive graph above and graphs of ML vs L (equation 5.1.10) and Y vs L (equation 5.1.11) are all HYPERBOLAs

To get a "gut" level understanding of the graphs of \((ML) = (M_0)(L)/(K_D + L)\) and \(Y = L/(K_D+L)\), let's consider 3 different values or sets of values of free ligand:

- L = 0: This obviously gives ML = 0

- L = KD: \((ML) = (M_0)(L)/(L + L)= (M_0)(L)/(2L) = Mo/2\) which indicates that M is half saturated. In fact the operational definition of KD is the ligand concentration at which the M is half saturated.

- L >> KD: ML = M0 and the macromolecule is saturated with ligand.

Case 2 (more general):

This applies when you know KD, but don't know free L or haven't measured it, and you just wish to calculate how much ML is present at equilibrium, given a KD value. In this case, L0 does not have to be much greater than M0. If where, like it is often in an experimental system, you would know that free L = L0 and you could use Case 1.

In this case, we will substitute mass balance equations for both M0 (Eq 5.1.2) and L0 (Eq 5.1.3)and into the equation for KD (Eq. 5.1.1). This gives:

\begin{equation}

\begin{gathered}

K_D=([M][L]) /[M L]=\left[M_0-M L\right]\left[L_0-M L\right] /[M L] \\

(M L) K_D=\left(M_0-M L\right)\left(L_0-M L\right) \\

(M L) K_D=\left(M_0\right)\left(L_0\right)-(M L)\left(L_0\right)-(M L)\left(M_0\right)+(M L)^2

\end{gathered}

\end{equation}

or

\begin{equation}

(M L)^2-\left(L_0+M_0+K_D\right)(M L)+\left(M_0\right)\left(L_0\right)=0

\end{equation}

This can be rearranged into the form \(ax^2 + bx + c = 0\) where

- a = 1

- b = - (L0 + M0 +KD)

- c = (M0)(L0)

with the well known solution \(x = [(-b) - (b^2 - 4(a)(c))^{1/2}]/2a\). Therefore,

\begin{equation}

(M L)=\left[\left(L_0+M_0+K_D\right)-\left(\left(L_0+M_0+K_D\right)^2-4\left(M_0\right)\left(L_0\right)\right)^{1 / 2}\right] / 2

\end{equation}

An interactive plot of the Y, fractional saturation, vs total L (L0) is shown below. Vary the sliders and note the changes in the graph.

In the derivations, we came up with two equations for ML, Eq 5.1.10 which gives ML vs L and Eq 5.1.16 which gives ML vs L0.

Both equations are valid. In the first, you must know free L which is often L0 if M0 << L0. In the second, you don't need to know free M or L at all. At a given Lo, Mo, and KD, you can calculate ML, which should be the same ML you get from the first equation if you know free L.

Equations 5.1.10 and 5.1.16 are useful in several circumstances. They can be used to

- calculate the concentration of ML if KD, M0, and L (for Eq. 5.1.10) or if KD, M0, and L0 (for Eq. 5.1.16) are known. This is analogous to the use of the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation to calculate the protonation state (HA) and hence the charge state of an acid at various pH values. In the former bind case, we are measuring the concentration of a reversibly bound ligand (ML) and in the latter case, the concentration of covalently bound protons (HA).

- calculate KD if ML, M0, and L (for Eq. 5.1.10) or if ML, M0, and L0 (for Eq. 5.1.16) are known. Techniques to extract the KD from binding data will be discussed in A separate chapter section.

Interpretation of Binding Analyzes

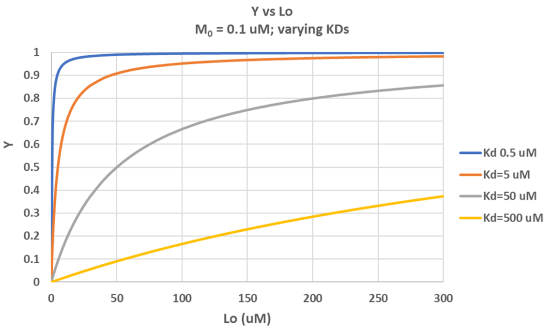

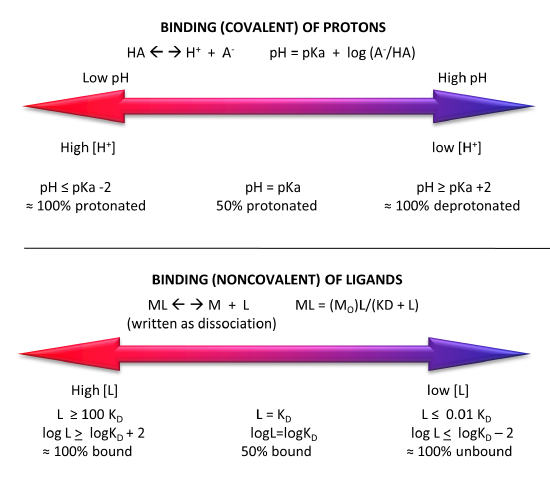

It is important to get a mathematical understanding of the binding equations and graphs. It is equally important to get an intuitive understanding of their properties. Just as we used the +/- 2 pH rule in determining at a glance the charge state of an acid, you need to be able to determine the extent of binding (how much of M is bound with L) given their relative concentrations and the KD. The usual situation is that [M0] is << [L0]. What happens to the binding curves for M + L ↔ ML if the KD gets progressively lower? Intuitively, you should expect that binding will increase, especially as L gets greater. The curves below should help you develop the intuition you need with respect to binding equilibria. Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) show Y vs L0 at Varying KDs

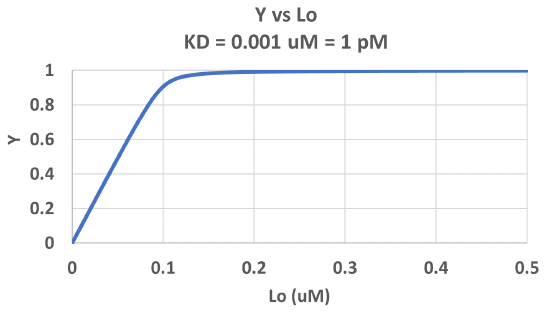

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) shows Y vs L0 at a very low KD (0.001 uM = 1 nM, resulting in a sharp "titration" curve. Any increment of L added is bound so effectively none is present in the free form. The graph abruptly changes to a horizontal line when all the macromolecule is bound. This curve could be used to determine [M0]!

Note that in the last graph, given the same M0 and L0 concentrations, the "titration curves" for a binding equilibrium characterized by even tighter binding (for example, a KD = 0.1 pM or 0.01 pM) would be indistinguishable from the graph when KD = 1 pM. It should be apparent that for all of these KD values, all of the added ligand is bound until [L0] > [M0]. To differentiate these cases, much lower ligand concentrations would be required such that on the addition of ligand, all is not bound. Also note that this curve is NOT hyperbolic, which makes sense since the graph is of Y vs L0, not Y vs L, and since L0 is not >> M0.

The interactive graph below shows fractional saturation Y vs L at two different KD values

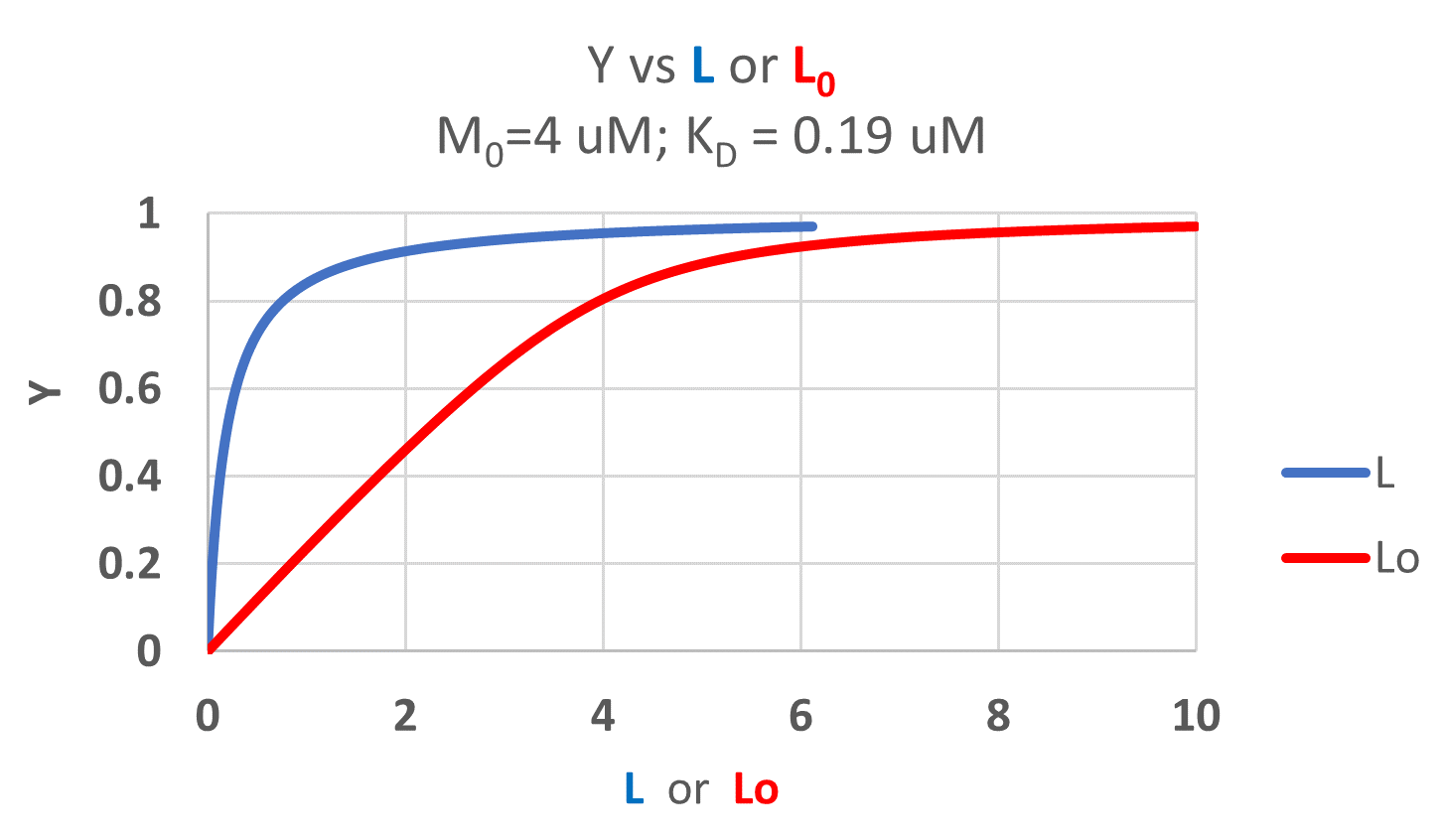

It is quite interesting to compare graphs of Y (fractional saturation) vs L (free) and Y vs Lo (total L) in the special case when L0 is not >> M0. Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) when M0 = 4 μM, Kd = 0.19 μM . Under the ligand concentration used, it should be apparent the L can't be approximated by L0

Two points should be evident from these graphs when L is not approximated by Lo:

- a graph of Y vs L0 is not truly hyperbolic, but it does saturate

- a KD value (ligand concentration at half-maximal binding) can not be estimated by inspection from the Y vs L0, but it can be from the Y vs L graph.

Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\) shows a comparison of the extent of covalent binding of a proton to an acid at pH values around the pKa and by analogy the extent of noncovalent binding of a ligand at log[L] values around the log KD.

Different Graphical Analyzes of Binding

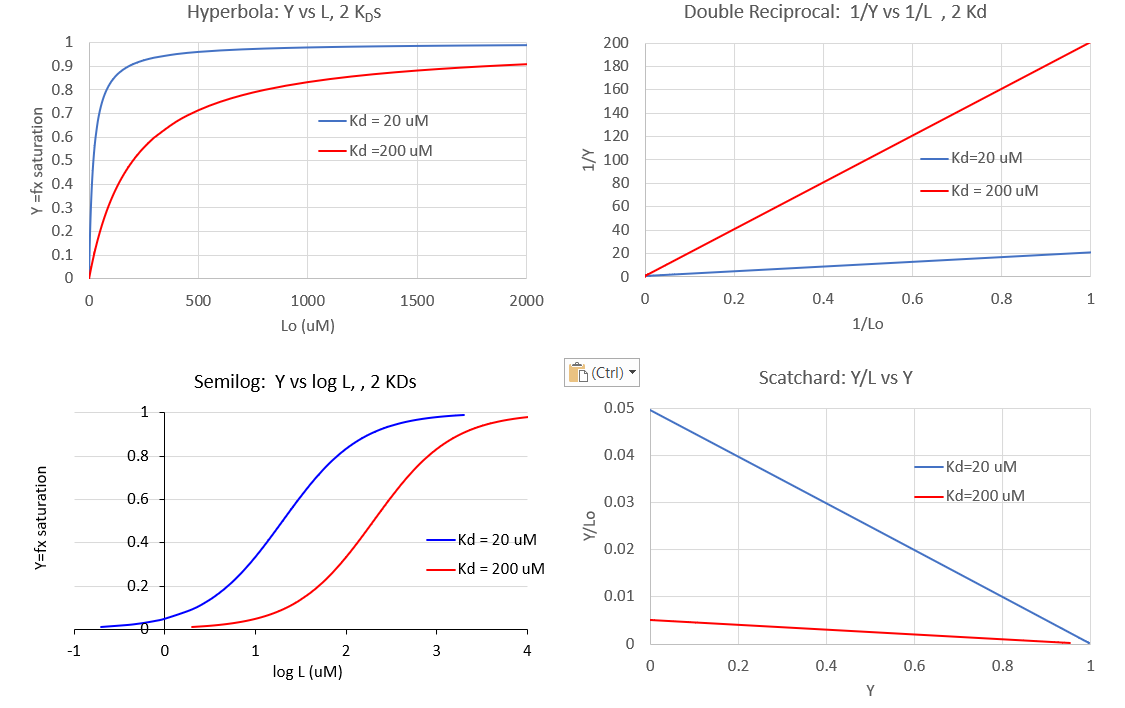

In addition to the hyperbolic plots of [ML] vs [L] and fractional saturation Y vs [L], a variety of derivative plots are often encountered. The equations and their graphs (for two different KD values, are shown below. The graphs are in the form of Y vs L0, when L0 is approximately equal to free L.

Hyperbolic saturation plot:

\begin{equation}

\mathrm{Y}=\frac{\mathrm{L}}{\mathrm{K}_{\mathrm{D}}+\mathrm{L}}

\end{equation}

Double reciprocal plot:

\begin{equation}

\frac{1}{\mathrm{Y}}=\frac{\mathrm{K}_{\mathrm{D}}+\mathrm{L}}{\mathrm{L}}=\frac{\mathrm{K}_{\mathrm{D}}}{\mathrm{L}}+1=\mathrm{K}_{\mathrm{D}}\left(\frac{1}{\mathrm{~L}}\right)+1

\end{equation}

A plot of 1/Y vs 1/L has a slope of KD and a y intercept of 1 (which is the number of binding sites for this simple mechanism)

The Scatchard plot:

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

\mathrm{Y}\left(\mathrm{K}_{\mathrm{D}}+\mathrm{L}\right) &=\mathrm{L} \\

Y\left(\mathrm{~K}_{\mathrm{D}}\right)+Y L &=L \\

Y\left(\mathrm{~K}_{\mathrm{D}}\right)=L-\mathrm{YL} &=\mathrm{L}(1-\mathrm{Y})

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}

which gives the final Scatchard plot equation:

\begin{equation}

\frac{Y}{\mathrm{~L}}=\frac{1-\mathrm{Y}}{\mathrm{K}_{\mathrm{D}}}=-\frac{\mathrm{Y}}{\mathrm{K}_{\mathrm{D}}}+\frac{1}{\mathrm{~K}_{\mathrm{D}}}

\end{equation}

A plot of Y/L vs Y has a slope of -1/KD and a y intercept of 1/KD.

Plotting Y vs L give a hyperbola, but a plot of Y vs log L give a sigmoidal plot. Plots of Y vs log L are often used in the research literature instead of traditional hyperbolic plots of Y vs L. There are several reasons for this:

- the log [L] is more fundamentally related to the thermodynamic expression that relates ΔG0 and Keq or KD, namely

\begin{equation}

\Delta G^0=-R T \ln K_{e q}=R \operatorname{Tln} K_D

\end{equation}

- plots of Y vs L plateau over a very large range of [L], but given the compression of the X axis values in a semilog plot, the plots reach a saturation plateau over a much narrower range of log [L]. A range from 1-100 on the [L] scale becomes 0-2 on the log [L] scale. Since it takes a very high concentration of ligand to truly reach saturation (100xKD), it's much easier to see if saturation is achieved in semilog plots.

- multiple plots of binding data for different KD values have exactly the same shape on a semilog plot. Binding data for a ligand to a wild type and mutant proteins, all with different KDs, will give identical plots with curves for higher KD values shifted to the right. Semilog plots are also used routinely to display multiple plots of binding in the absence and presence of a binding inhibitor.

Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\) show different graphs for ligand binding to a macromolecule

Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\): Different graphs for ligand binding to a macromolecule

The graph of Y vs log [L] is sigmoidal but the same data would give a hyperbola if plotted as Y vs [L]. However, as we will see in section 5.3, there are some occasions when the graph of Y vs [L] is sigmoidal. For example, this can occur when the binding of a ligand to a multimeric binding protein affects the binding of the ligand to additional sites on the protein. This is an example of allosteric binding, which we will explore in great detail in section 5.3. So if you see a sigmoidal plot, be careful to examine the graph to see if it is a regular or semilog plot.

Straight line transformations of the hyperbolic binding equations are useful to get approximate values of KD, but linear regression analysis to get slopes and intercepts is not statistically optimal as the errors in the y variable (Y) and in the y and x variables in the Scatchard plot are not identical across values. To determine KD, it is best to fit experimental data to the nonlinear function for the hyperbola.

Dimerization and Multiple Binding Sites

In the previous examples, we considered the case of a macromolecule M binding a ligand L at a single site, as described in the equation below:

M + L ↔ ML

where KD = [M][L]/[ML]

We saw that the binding curves (ML vs L or Y vs L are hyperbolic, with a KD = L at half-maximal binding. But there are many other chemical equilibria than can mechanistically explain binding data. We'll consider just two cases here.

Dimerization

A special, yet common example of this equilibrium occurs when a macromolecule binds itself to form a dimer (D), as shown below:

M + M ↔ M2 or D

where D is the dimer, and where

\begin{equation}

K_D=[M][M] /[D]=[M]^2 /[D]

\end{equation}

At first glance, you would expect a graph of [D] vs [M] to be hyperbolic, with the KD again equaling the [M] at half-maximal dimer concentration. This turns out to be true, but a simple derivation is in order. In the case of dimer formation, Mo, which superficially represents both M and L in the earlier derived expression, are both changing. So we have to invoke mass balance of M again: \([Mo] = [M] + 2[D]\), where the coefficient 2 is necessary since there are 2 M in each dimer.

More generally, for the case of the formation of trimers (Tri), tetramers (Tetra), and other oligomers, \([Mo] = [M] + 2[D] + 3[Tri] + 4[Tetra] + ....\)

Rearranging (12) and solving for D gives \(D = ([M_0] - [M])/2\). Substituting this into the KD expression (1) gives

\begin{equation}

K_D=\frac{M^2}{\frac{\left[M_0\right]-[M]}{2}}=\frac{2 M^2}{\left[M_0\right]-[M]}=

\end{equation}

This can be rearranged into quadratic form for M (not D):

\begin{equation}

2 M^2+K_D(M)-K_D\left(M_0\right)=0

\end{equation}

which is of the form y = ax2+bx+c.

Solving the quadratic equation gives [M] and with M0 , D can be calculated from \(D = ([M_0]-[M])/2\).

A value Y, similar to fractional saturation, can be calculated, where Y is the fraction of total possible D, which can vary from 0-1: \(Y= 2D/M_0\)

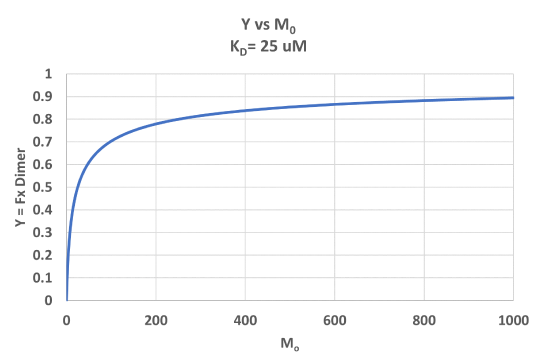

A graph of Y vs Mo with a dimerization dissociation constant KD = 25 uM, is shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\).

Note that the curve appears somewhat hyperbolic. Half-maximal dimer formation does occur at a total M concentration M0 = KD. Also note, however, that even at M0 = 1000 uM, which is 40x KD, only 90% of the total possible D is formed (Y = 0.90). For the simple M + L ↔ ML equilibrium, if L0 = 40x the KD and M0 << L0, \(Y = L/(K_D+L) = L/[(L/40)+L] = 0.976\)

An interactive graph showing Y (the fraction of dimers) vs M0 is show. Move the sliders to show how changes in "KD" affect the dimerization.

The aggregation state of a protein monomer is closely linked with its biological activity. For proteins that can form dimers, some are active in the monomeric state, while others are active as a dimer. High concentrations, found under conditions when proteins are crystallized for x-ray structure analysis, can drive proteins into the dimeric state, which may lead to the false conclusion that the active protein is a dimer. Determination of the actual physiological concentration of [Mo] and KD gives investigators knowledge of the Y value which can be correlated with biological activity. For example, interleukin 8, a chemokine, which binds certain immune cells, exists as a dimer in x-ray and NMR structural determinations, but as a monomer at physiological concentrations. Hence the monomer, not the dimer, binds its receptors on immune cells. Viral proteases (herpes viral protease, HIV protease) are active in dimeric form, in which the active site is formed at the dimer interface.

Binding of a ligand to two independent sites

What if a ligand L binds to two different sites on the same biomacromolecule? Assuming that the binding of ligand L to one site does not affect the binding of the ligand to the other site (and vice versa), the following equation can be simply derived:

\begin{equation}

Y=\left[\frac{L}{\left(K_{D 1}+L\right)}+\frac{L}{\left(K_{D 2}+L\right)}\right] / 2

\end{equation}

The numerator of the equation has a term for the fractional saturation of site 1 characterized by KD1 and a term for the fractional saturation of site 2 characterized by KD2. These two terms are divided by 2 so that the fractional saturation of all sites is 1 at saturating values of free ligand. Note that there can only be one free ligand concentration in solution so the only thing that differs in the two terms in the numerator is the KD value.

The interactive graph below shows such binding to two independent sites with different KD values. Again, we'll assume the binding of one ligand does NOT influence the binding of the other.

The Binding Continuum

Binding affinities give us a way to measure the relative strength of binding between two substances. But how "tight" is tight binding? Weak binding? Let us exam that issue by considering a binding continuum. Consider two substances, A and B that might interact. Over what range of strengths can they actually bind to each other? It would helpful to set up the extremes of the binding continuum. At one end is no binding at all. At the other end, consider two things that bind covalently. We have discussed how Kd reflects binding strength. Remember, KD = 1/Keq. Also, we know that Keq is related to ΔGo by the equations:

\begin{equation}

\Delta G^0=-R \operatorname{Tln} K_{e q}=R \operatorname{Tln} K_D

\end{equation}

Given these simple equations, you should be able to interconvert between Keq, KD, and ΔG0. (Keep your units straight.).

No interaction: One end of the binding continuum represents no interaction. Let's assume that Keq is tiny (KD large), for example Keq~ 2.4 x10-72. Plugging this into the equation \(ΔG^0 = - RTlnK_{eq}\), where R = 2.00 cal/mol.K, and T is about 300K, the ΔG0 ~ +100 kcal/mol (418 kJ/mo). That is, if we add A + B, there is no drive to form AB. If AB did form, then it would immediately fall apart.

Covalent interaction: At the other end of the continuum consider the interaction of 1H atom with another to form H2. From a general chemistry book we can get ΔG0form. Using simple thermodynamics, we can calculate ΔGo for H-H formation. (ΔGo = ΣΔG0form prod. - ΣΔG0form react.) Doing this gives a value of -97 kcal/mol (-406 kJ/mol).

Specific and Nonspecific Binding: Consider the interaction of a protein, the lambda repressor (R), with a small oligonucleotide to which it binds tightly (called the operator DNA, O). This is an example of a biologically tight, but reversible interaction. R can bind to many short oligonucleotides due to electrostatic interactions and H bonds between the positively charged protein and the negatively charged nucleic acid backbone. The tight binding interaction, however, involves oligonucleotides of a specific base sequence. Hence we can distinguish between tight binding, which usually involves specific DNA sequences and weak binding which involves nonspecific sequences. Likewise, we will speak of specific and nonspecific binding. R and O, which bind with a KD of 1 pM, represent an example of specific binding, while R and nonspecific DNA (D), which bind mostly through electrostatic interactions with a KD of 1 mM, are an example of nonspecific binding. You might expect any positively charged protein, like mitochondrial cytochrome C, would bind negatively charged DNA. This nonspecific interaction would presumably have no biological significance since the two are localized in different compartments of the cell. In contrast, the interaction between positively charged histone proteins, bound to DNA in the nucleus, would be specific.

Rate constants for association and dissociation: When the reaction

M + L ↔ ML is at equilibrium, the rate of the forward reaction is equal to the rate of the reverse reaction. From General Chemistry, the forward reaction is biomolecular and second order. Hence the vf, the rate in the forward direction is proportional to [M][L], or

\(v_f = k_f[M][L]\), where kf is the rate constant in the forward direction. The rate of the reverse reaction, vr is first order, proportional to [ML], and is given by \(v_r = k_r [ML]\), where kr is the rate constant for the reverse reaction. Notice that the units of kf are M-1s-1, while units of kr are s-1. At equilibrium, \(v_f = v_r\), or

\begin{equation}

k_f[M][L]=k_r[M L]

\end{equation}

Rearranging the equation gives

\begin{equation}

[M L] /[M][L]=k_f / k_r=K_{e q}

\end{equation}

Hence Keq is given by the ratio of rate constants. For tight binding interactions, Keq >> 1, KD << 1, and kf is very large (in the order of 108-9 ) and kr must be very small (10-2 - 10 -4 s-1).

To get a more intuitive understanding of KDs, it is often easier to think about the rate constants which contribute to binding and dissociation. Let us assume that kr is the rate constant that describes the dissociation reaction. It is often times called koff. Likewise, kf is often called the on rate (kon). It can be shown mathematically that the rate at which two simple molecules associate depends on their radius and effective molecular weight. The maximal rate at which they will associate is the maximal rate at which diffusion will lead them together. Let us assume that the rate at which M and L associate is diffusion limited. The theoretical kon is about 108 M-1s-1. Knowing this, the KD and the fact that kon/ koff = Keq = 1/KD, we can calculate koff, which is a first-order rate constant.

We can also determine koff experimentally. Imagine the following example. Adjust the concentrations of M and L such that Mo << Lo and Lo>> Kd. Under these conditions of ligand excess, M is entirely in the bound from, ML. Now at t = 0, dilute the solution so that Lo << Kd. The only process that will occur here is dissociation, since negligible association can occur given the new condition. If you can measure the biological activity of ML, then you could measure the rate of disappearance of ML with time, and get koff. Alternatively, if you could measure the biological activity of M, the rate at which activity returns will give you koff.

Now you will remember from Introductory Chemistry that for a first-order rate constant, the half-life (t1/2) of the reaction can be calculated by the expression: k = 0.693/t1/2. Hence given koff, you can determine the t1/2 for the associated specie's existence. That is, how long will a complex of ML last before it dissociates? Given ΔGo or KD, and assuming a kon (108 M-1s-1), you should be able to calculate koff and t1/2. Or, you could be able to determine koff experimentally, and then calculate t1/2. Applying these principles, you can calculate the binding parameters. Table \(\PageIndex{1}\) below shows calculated koff and t1/2 for binary complexes assuming diffusion-controlled kon.

| Complex | KD (M) | koff (s-1) | t½ |

| H2 | 1 x 10-71 | 1 x 10-63 | 2 x 1055 yr |

| RtV3 : Rt'L3(a) | 10-17 | 1 x 10-9 | 2 yr |

| Avidin:biotin | 10-15 | 1 x 10-7 | 80 days |

| thrombin:hirudin(b) | 5 x10-14 | 5 x 10-6 | 2 days |

| lacrep:DNAoper(c) | 1 x 10-13 | 1 x 10-5 | 0.8 days |

| Zif268:DNA(d) | 10-11 | 1 x 10-3 | 700 s |

| GroEL:r-lactalbumin(e) | 10-9 | 0.1 | 7 s |

| TBP:TATA(f) | 2 x 10-9 | 2 x 10-1 | 3 s |

| TBP:TBP | 4 x 10-9 | 4 x 10-1 | 2 s |

| LDH (pig): NADH(g) | 7.1x10-7(j) | 7.1 x 101 | 10 ms |

| profilin: CaATP-G-actin | 1.2 x 10-6 | 1.2 x 102 | 6 ms |

| TBP: DNAnonspec(h) | 5 x 10-6 | 5 x 102 | 1 ms |

| TCR(i): cyto C peptide | 7X10-5 | 7X103 | 100 us |

| lacrep:DNAnonspec(h) | 1 x 10-4 | 1 X104 | 70 us |

| uridine-3P: RNase | 1.4x10-4 (j) | 1.4X104 | 50 us |

| Creatine Kinase: ADP | 8.2x10-4 (j) | 8.2X104 | 10 us |

| Acetylcholine:Esterase | 1.2 x 10-3 | 1.2 x 105 | 6 us |

| no interaction | 4 x 1073 | 4 x 1081 | - |

Table \(\PageIndex{1}\): Calculated koff and t1/2 for binary complexes assuming diffusion-controlled kon

- Trivalent Vancomycin derivative RtV3 + Trivalent D-Ala-D-Ala deriv, Rt'L3'

- Hirudin is a potent thrombin inhibitor from leach saliva

- lac rep is the E. Coli lac operon repressor protein, and DNAoper is the specific DNA binding region in the E. Coli genome that binds to the repressor

- Zif268 is a mouse zinc-finger binding protein

- GroEL is a chaperone protein; r-lactalbumin is the reduced form of lactalbumin

- TBP is the TATA Binding Protein that binds to the TATA box consensus sequence

- LDH is lactate dehydrogenase

- DNAnonspec is DNA which does not contain the specific DNA sequence region involved in specific

binding to a DNA binding protein - TCR is the T-cell receptor

- calculated from equation: KD = koff/kon.

What is usually measured is KD and/or koff (if the koff is reasonable). This analysis is very simplified. Electrostatic forces and other orientation factors may significantly change kon, while conformational changes in the complex may prevent ready unbinding of the bound ligand, dramatically altering koff.

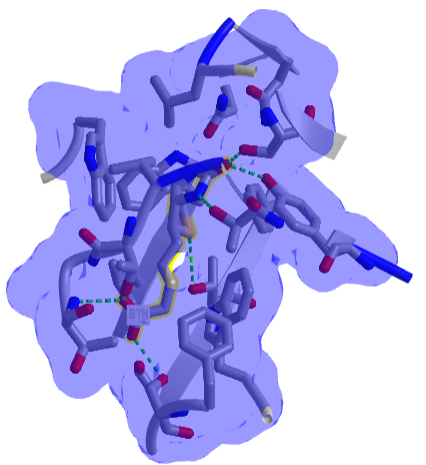

Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of one of the tightest binding complexes, avidin and biotin (2avi).

Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\): Avidin-Biotin Complex (2avi) (Copyright; author via source).

Click the image for a popup or use this external link: https://structure.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/i...ZssSe5GoUfr9Q6

The blue shows the surface around the complex, which shows that the avidin in completely buried. Hydrogen bonds are shown to biotin (labeled as BTN) in green dashes.

It is important to note that even reactions characterized by high KD (weak binding) can be specific. Specificity is ultimately defined as a binding interaction between a macromolecule and ligand that can be co-localized in the same environment and for which a biological function is elaborated upon binding.