4.4: Secondary Structural Motifs and Domains

- Page ID

- 26180

Common Structural Motifs

Given the number of possible combinations of 1o, 2o, and 3o structures, one might guess that the 3D structure of each protein is quite distinctive. This is in general true. However, it has been found that similar substructures are found in proteins. For instance, common secondary structures are often grouped together to form common structural motifs, often called super-secondary structures. Often the same motif is found in proteins with similar functions (such as proteins that bind DNA, Ca2+, etc). Let's explore some of the common motifs.

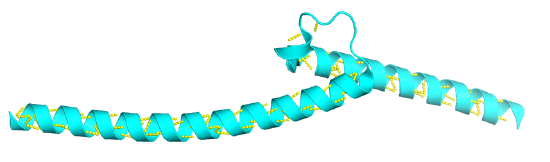

Alpha-loop-Alpha

These are found in DNA-binding proteins that regulate transcription and also in calcium-binding proteins, in which the motif is often called the EF hand. The loop region in calcium-binding proteins is enriched in Asp, Glu, Ser, and Thr. Why? The EF hand shown below is from calmodulin.

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of a basic helix-turn-helix from the c-Myc protein (1NKP). The iCn3D model shows the helices interacting with the major grove of DNA, which is shown in spacefill.

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Basic helix-turn-helix from the c-Myc protein (1NKP). (Copyright; author via source).

Click the image for a popup or use this external link: https://structure.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/i...kDv9DGzWWWoMZ8

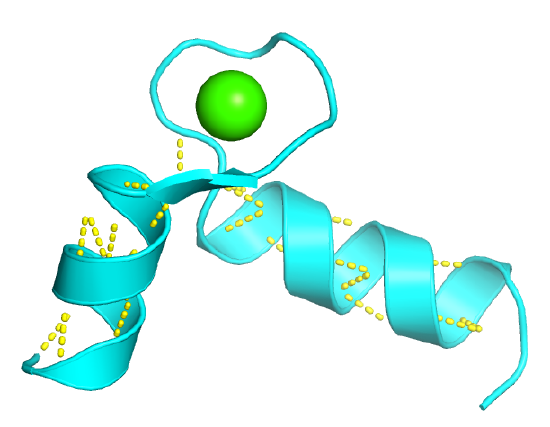

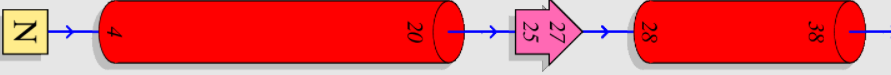

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of the "EF hand" from the calcium-binding protein calmodulin (1cll)

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): EF hand from Calmodulin (1cll): Secondary Structure Motif. (Copyright; author via source).

Click the image for a popup or use this external link: https://structure.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/i...J9jefZYfcpkRu8

The EF Hand can be envisioned as a hand gripping a ball (calcium ion) with the index finger and thumb representing alpha helices, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\).

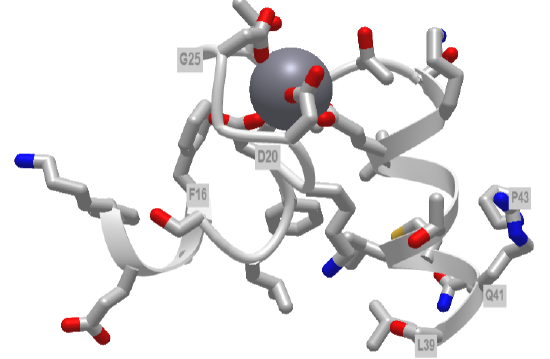

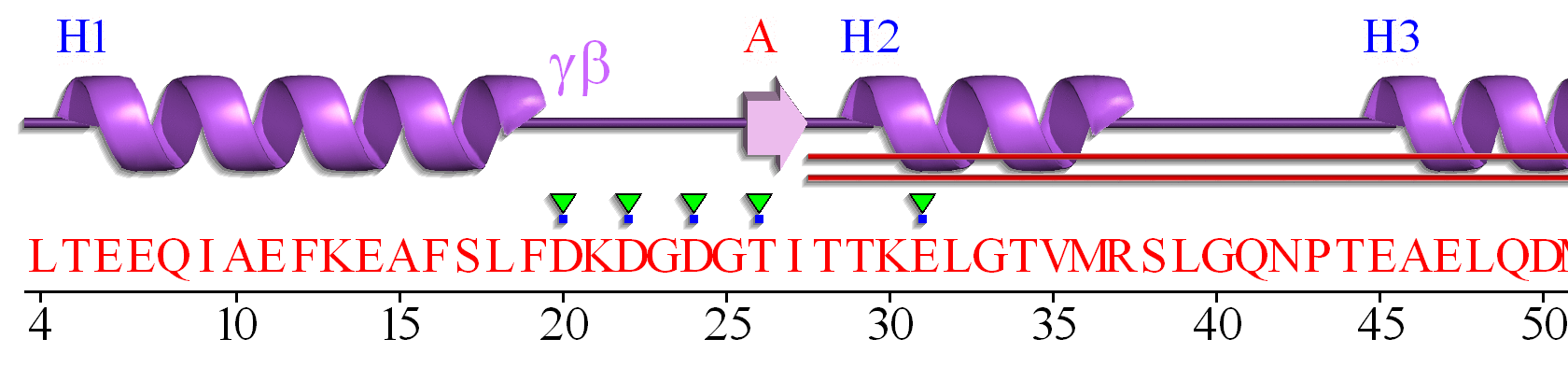

The EF hand motif of calmodulin is used in a variety of Ca2+ binding proteins. Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) shows the alignment of the first 50 residues of human calmodulin with four other human calcium-binding proteins. The EF hand (F12-L29) of calmodulin consists of the second half of the first helix (F12-L18), an intervening loop (F19-T28), and the second helix (T29-L29). Sometimes, it is annotated to encompass a larger stretch (8-43)

Part A shows the degree of conservation of amino acids in this first Ca2+-binding EF hand. Part B shows the general conservation of key hydrophobic (F12, F19, I27) as well additionally, those of similar polarity (36 and 39)

Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of the first EF hand in human calmodulin with key amino acids labeled.

Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\): First EF hand of Calmodulin (1cll) (Copyright; author via source).

Click the image for a popup or use this external link:https://structure.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/i...c6YcMn9dj77Wr9

Hover over the amino acid side chains that are coordinating the Ca2+ ion. Are they what you would expect?

A linear connectivity "wiring" diagram showing secondary structure connected by connecting regions is shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\). This particular wiring diagram shows a 2-residue beta strand, which is insignificant in length to be considered an actual strand.

A more complicated 2D topology map is shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\). In this case, it is linear given the small section of amino acids depicted. We will see more complicated 2D topology maps with more complicated structures below.

It is presented on its side to save space on this page.

Beta-hairpin or beta-turn

This motif is present in most antiparallel beta structures, both as an isolated ribbon and as part of beta sheets.

Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of the beta hairpin from bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor (1k6u)

Beta hairpin from bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor (1k6u)

Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\): Beta hairpin from bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor (1k6u) (Copyright; author via source).

Click the image for a popup or use this external link: https://structure.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/i...eMFdHkGogJHCCA

Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\) shows the 2D homology map for the beta-hairpin.

Greek Key

The "Greek Key" symbol represents infinity and the eternal flow of things and resembles in part primitive keys. The Greek Key motif in proteins can be seen in the structure of antiparallel beta sheets in the ordering of four adjacent antiparallel beta strands as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\). The figure also shows the repetitive Greek key, which you will see many times if you visit Greece and tour its antiquities.

Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\)s shows a partial 2D topology map of Staphylococcus nuclease (2SNS).

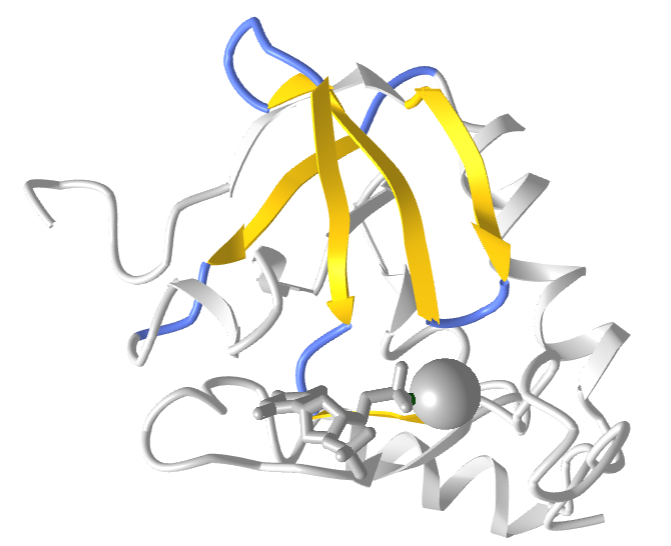

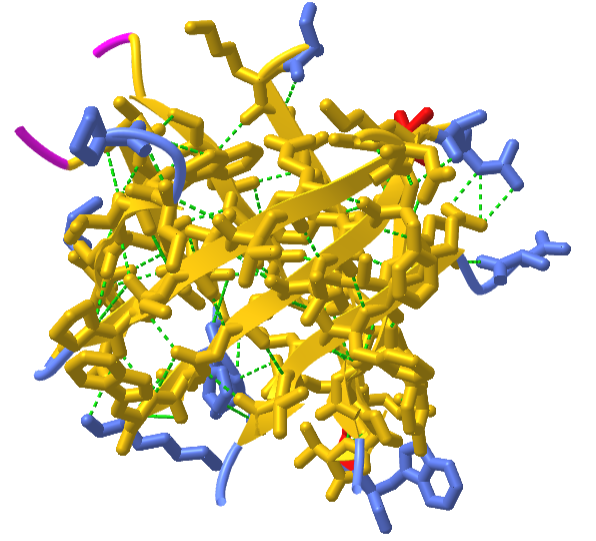

Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of the Greek Key motif from Staphylococcus nuclease (2SNS). The involved beta strands are shown in yellow.

Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\): Greek Key motif from Staphylococcus nuclease (2SNS) (Copyright; author via source).

Click the image for a popup or use this external link: https://structure.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/i...x2ef4xpttXrFb9

Beta-Alpha-Beta

The motif is a common way to connect two parallel beta strands as compared to beta hairpins, which are used to connect antiparallel beta strands.

Figure \(\PageIndex{12}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of the beta-alpha-beta structure from triose phosphate isomerase (1amk).

Figure \(\PageIndex{13}\) shows the 1D wiring diagram for the first beta-alpha-beta motif in triose phosphate isomerase.

Figure \(\PageIndex{14}\) shows the 2D topology diagrams showing this motif.

Larger Structural Motifs - Protein Architecture

Some proteins combine larger secondary and supersecondary structural components, often in a repeated fashion to produce more complex structures. We've seen this with larger twisted sheets and beta barrels, such as the TIM barrel. Let's consider three of these, which can be considered examples of protein architectures without considering connectivity within the protein.

The Rossman Fold

Structural motifs can serve particular functions within proteins such as enabling the binding of substrates or cofactors. For example, the Rossmann fold is responsible for binding to nucleotide cofactors such as nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{15}\). The Rossmann fold is composed of six parallel beta strands that form an extended beta sheet. The first three strands are connected by α-helices resulting in a beta-alpha-beta-alpha-beta structure. This pattern is duplicated once to produce an inverted tandem repeat which contains six strands. Overall, the strands are arranged in the order of 321456 (1 = N-terminal, 6 = C-terminal). Five stranded Rossmann-like folds are arranged in the sequential order 32145. The overall tertiary structure of the fold resembles a three-layered sandwich wherein the filling is composed of an extended beta sheet and the two slices of bread are formed by the connecting parallel alpha helices.

Image modified from: Boghog

One of the features of the Rossmann fold is its co-factor binding specificity. The most conserved segment of Rossmann folds is the first beta-alpha-beta segment. Since this segment is in contact with the ADP portion of dinucleotides such as FAD, NAD and NADP it is also called as an "ADP-binding beta-beta fold".

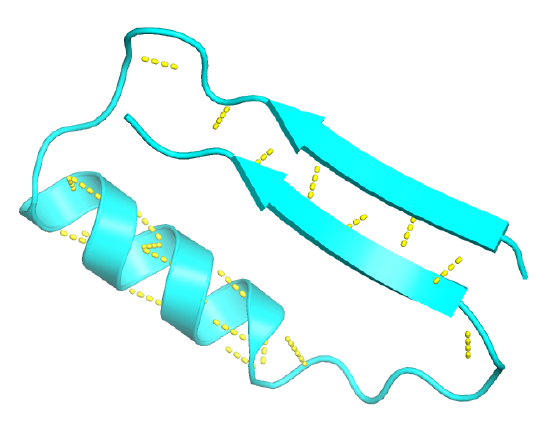

Figure \(\PageIndex{16}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of the Rossman fold of malate dehydrogenase (5KKA) from E. Coli. The beta strands (yellow) and connecting alpha helices (red), and coil (blue) of the Rossman fold are shown in the context of the rest of the monomeric version of the protein, which is shown in gray.

The TIM barrel revisited

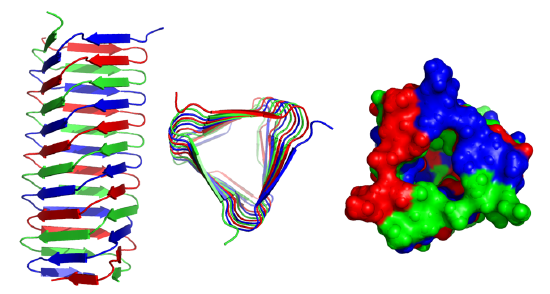

Interestingly, similar structural motifs do not always have a common evolutionary ancestor and can arise by convergent evolution. This is the case with the TIM Barrel, a conserved protein fold consisting of eight α-helices and eight parallel β-strands that alternate along the peptide backbone. It is illustrated in Figure \(\PageIndex{17}\). The structure is named after triosephosphate isomerase, a conserved metabolic enzyme. TIM barrels are one of the most common protein folds. One of the most intriguing features among members of this class of proteins is although they all exhibit the same tertiary fold there is very little sequence similarity between them. At least 15 distinct enzyme families use this framework to generate the appropriate active site geometry, always at the C-terminal end of the eight parallel beta-strands of the barrel.

Image modified from: WillowW

Although the ribbon diagram of the TIM Barrel shows a hole in the protein's central core, the amino acid side chains are not shown in this representation (Figure 2.26). The protein's core is actually tightly packed, mostly with bulky hydrophobic amino acid residues although a few glycines are needed to allow wiggle room for the highly constrained center of the 8 approximate repeats to fit together. The packing interactions between the strands and helices are also dominated by hydrophobicity and the branched aliphatic residues valine, leucine, and isoleucine comprise about 40% of the total residues in the β-strands.

The figure \(\PageIndex{18}\) below shows an interactive iCn3D model of the TIM barrel (1WYI) from Chapter 4.2).

.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=317&height=288)

As our knowledge continues to increase about the myriad of structural motifs found in nature's treasure trove of protein structures, we continue to gain insight into how protein structure is related to function and are better enabled to characterize newly acquired protein sequences using in silico technologies.

Beta Helices

These right-handed parallel helical structures consist of a contiguous polypeptide chain with three parallel beta strands separated by three turns forming a single rung of a larger helical structure which in total might contain as many as nine rungs. The intrastrand H-bonds are between parallel beta strands in separate rungs. These seem to prevalent in pathogens (bacteria, viruses, toxins) proteins that facilitate the binding of the pathogen to a host cell.

Figure \(\PageIndex{19}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of the C-terminal fragment of the phage T4 GP5 beta helix (4osd).

Beta helices and found in the following organisms (with the diseases they cause in humans): Vibrio cholerae (cholera), Helicobacter pylori (ulcers), Plasmodium falciparum (malaria), Chlamyidia trachomatis (VD), Chlamydophilia pneumoniae (respiratory infection), Trypanosoma brucei (sleeping sickness), Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme disease), Bordetella parapertussis (whooping cough), Bacillus anthracis (anthrax), Neisseria meningitides (menigitis) and Legionaella pneumophilia (Legionaire's disease).

Beta Propellors

Protein with this structure has 4-8 blade-shaped beta sheets arranged around a central axis, forming an active site shaped like a funnel.

Figure \(\PageIndex{20}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of the C-terminal domain of Tup1 (1ERJ), a yeast transcription factor, which has a seven-bladed beta propeller. Each blade contains a WD40 repeat sequence (around 40 amino acids) that often ends in tryptophan-aspartic acid (W-D). The particular protein has four WD dipeptides sequences, shown in sticks colored with CPK colors.

The funnel provides binding sites for proteins and other molecules, with the ones with more blades usually acting as enzymes.

Domains

Domains are the fundamental unit of 3o structure. Domains can be considered a chain or part of a chain that can independently fold into a stable tertiary structure. Domains are units of structure but can also be units of function. Some proteins can be cleaved at a single peptide bond to form two separate domains. Often, these can fold independently of each other, and sometimes each unit retains an activity that was present in the uncleaved protein. Sometimes binding sites on the proteins are found in the interface between the structural domains. Many proteins seem to share functional and structural domains, suggesting that the DNA of each shared domain might have arisen from the duplication of a primordial gene with a particular structure and function.

Evolution has led toward increasing complexity which has required proteins of new structure and function. Increased and different functionalities in proteins have been obtained with addition of domains to base proteins. Chothia (2003) has defined domain in an evolutionary and genetic sense as "an evolutionary unit whose coding sequence can be duplicated and/or undergo recombination". Proteins range from small with a single domain (typically from 100-250 amino acids) to large with many domains. From recent analyzes of genomes, new protein functionalities appear to arise from the addition or exchange of other domains which, according to Chothia, result from

- duplication of sequences that code for one or more domains

- divergence of duplicated sequences by mutations, deletions, and insertions that produce modified structures that may have useful new properties to be selected

- recombination of genes that result in novel arrangement of domains.

Structural analyzes show that about half of all protein-coding sequences in genomes are homologous to other known protein structures. There appear to be about 750 different families of domains (i.e. small proteins derived from a common ancestor) in vertebrates, each with about 50 homologous structures. About 430 of these domain families are found in all the genomes that have been solved.

Proteins with multiple domains also are more likely not to misfold if each domain can fold somewhat autonomously. In addition, they provide a myriad of binding sites which increase the number of biological functions expressed in a single protein. Multidomain proteins can also express multiple catalytic activities, allowing for a reaction product from one domain to diffuse to another catalytic domain (or interface between domains). This would reduce the dimensionality of the search for a substrate from 3D to more of a 1D or 2D search, enormously speeding up the net reaction. The process is often called substrate channeling.

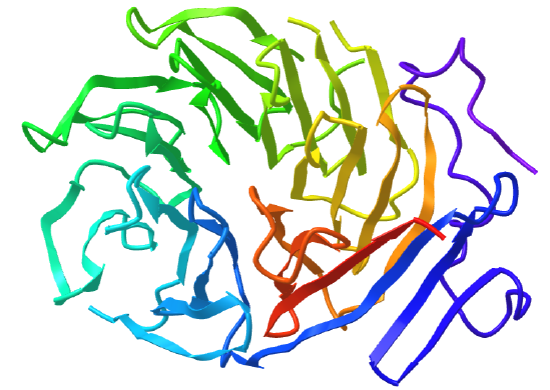

Figure \(\PageIndex{21}\) shows an interactive iCn3D model of the three domains of the enzyme pyruvate kinase (1pkn). These include a nucleotide (ADP/ATP) binding domain (blue) made of beta strands, a substrate binding domain (green) in the middle composed of alpha/beta structure, and a regulatory domain (red) composed of alpha/beta structure. These domains were analyzed by a web program called CATH-Gene3D.

The CATH programs offer a complete classification of protein structure based on the following hierarchy of organization: Class, Architecture, Topology, and Homologous Superfamilies - CATH.

- Class: the highest level of organization which consists of four classes - mainly alpha, mainly beta, alpha-beta, and few secondary structures

- Architecture (40 types): describes the shape of domain based on secondary structures but doesn't describe how they are connected. Ex: beta barrel, beta propeller

- Topology (or fold group, 1233 types): members in topology groups have a common fold or topology in the "core" of the domain structure.

- Homologous Superfamilies (2386 types): These groups are homologous in sequence or structure and derive from a common precursor gene/protein.

An alternative computer program, Pfam, shows this enzyme as having 2 major domains, a pyruvate kinase beta barrel domain and a pyruvate kinase alpha/beta domain.

Pfam domains are determined by sequence analysis while CATH are determined by structural comparisons. Domains determined by both programs show about a 75% overlap.

At a simpler level, domains are built from the kinds of motif structures we discussed above. Since proteins are very packed structures, the organizational structure of proteins can be thought of as closely packed motifs, but not all possible combinations are found. For example, if you have one beta hairpin next to another to form a 2-unit Greek key, there are 24 likely ways to connect them but only eight are common. The two below appear to account for more than the sum of the other 22. These are shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{22}\).

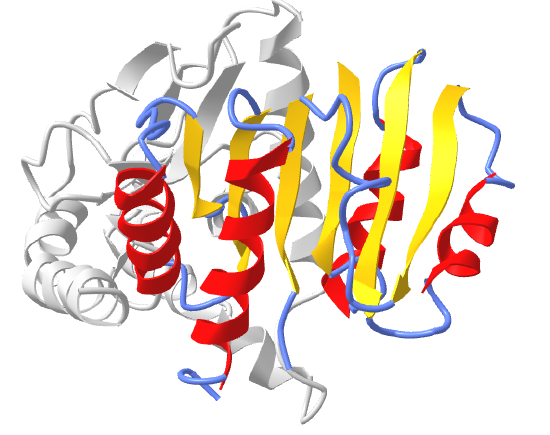

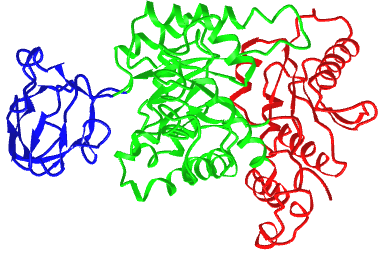

Figure \(\PageIndex{23}\) shows an example of the architecture of the multi-domain protein, human Attractin-like protein 1. This protein is an example of a lectin, a carbohydrate-binding protein, which we will explore in a subsequent chapter. It binds Ca2+, so it is considered a C-Lectin. Three different programs were used to analyze the domain structure.

Figure \(\PageIndex{23}\): Architecture of the multi-domain protein, human Attractin-like protein 1